Powell’s Pals: A Comparative Summary of Colleagues

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a constellation of scientists who worked at or near John Wesley Powell’s orbit — mapping, collecting, classifying, preserving, debating, and often influencing governmental policy. These figures shared ambitions, resources, and institutional ties, yet their lives and work diverged sharply in background, scientific focus, public role, personality and legacy. The following sketches and tables compare nine of them — Clarence E. Dutton, Clarence R. King, James C. Pilling, Garrick Mallory, Charles D. Walcott, W J McGee, Cyrus Thomas, Gifford Pinchot and O. C. Marsh — highlighting what they held in common, how they differed, and what this collection of men reveals about the Powell era.

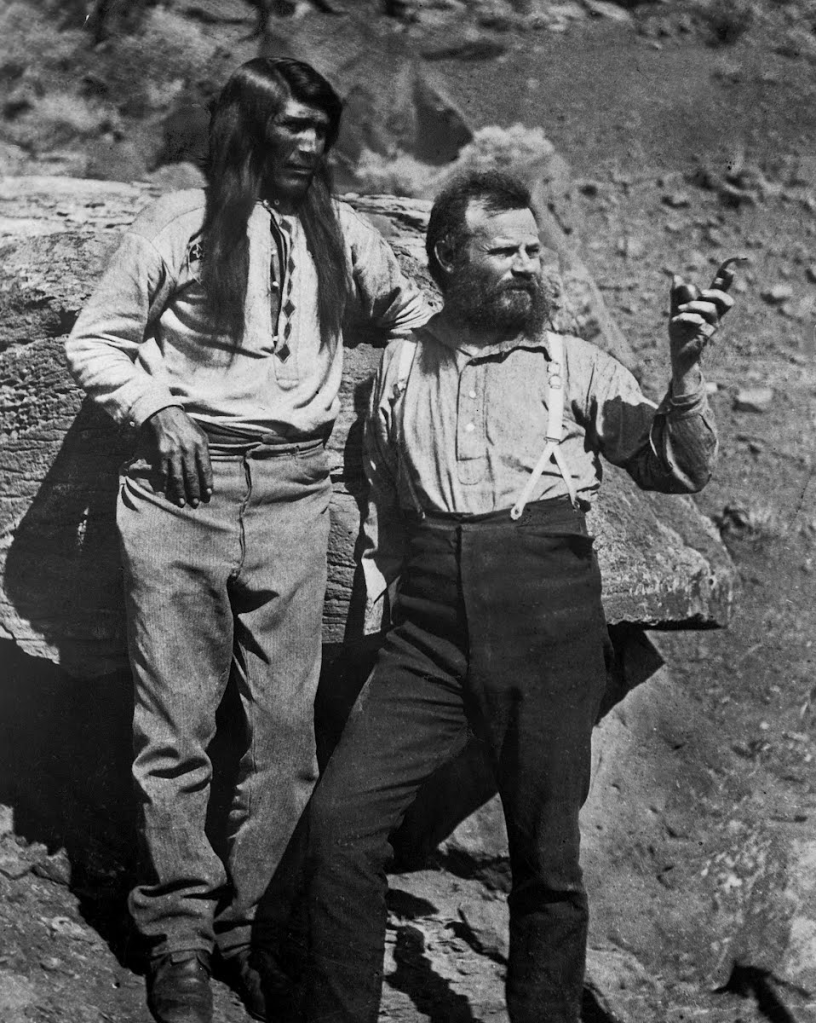

But before we introduce the nine other men, it’s important to understand and meet the star whose gravity encircled these men of science to begin with. His name is John Wesley Powell.

Brief Meet Up With John Wesley Powell — Explorer, Scientist, Visionary

John Wesley Powell was one of those rare people who wore many hats without losing his head and his curiosity. He was a soldier, geologist, explorer, teacher, ethnologist — and always someone who wanted to understand the land and its people. Born in New York, he was raised in Ohio, Wisconsin and Illinois — Powell was more interested in rivers, canyons, and native languages and what those disciplines taught him than in classroom studies and academic honors. Powell was destined to go on a deep journey of self-education and field work.

The Great Colorado River Voyage & The Arid West

After serving in the Civil War (and losing his right arm in the Battle of Shiloh), Major Powell didn’t settle down. In the late 1860s he climbed peaks (Pikes Peak, Longs Peak), rafted rivers (White River, Green River, Yampa River) and taught geology for a time (Professor of geology at Illinois Wesleyan University). Then in 1869, he led a small group of nine other explorers and topographers to boat down the Green River to the confluence with the Colorado River and beyond.[1] That unique expedition extended through enormous canyons, unknown rapids and uncharted territory. The journals and writings of the men were instructive. And although the men did not know if they would be able to climb out of the canyon alive (three men didn’t), when they emerged, months later, their stories and writings forever changed how Americans thought about the West.

Powell believed that the Western Frontier, beyond the 100th Meridian, was special, particularly its deserts, watersheds and Indigenous peoples. He recognized several characteristics: the land was fragile, the water would be scarce, and the ecological policies, and maps, if drawn without respect for nature, would cause conflict and create waste. His Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions and his work with the Bureau of Ethnology were attempts to marry hard-core science with topography and stewardship of the culturally sacred monuments.

Key Figures in Powell’s Circle

Of the hundreds of men who interacted with John Wesley Powell in this era, below are nine of them who surrounded him — each different, each essential to enhancing Powell’s vision of the Western territories. Interestingly, there were nine men who boated down the Colorado River in 1869, during their historic river trip through the Grand Canyon;[1] however, none of those enterprising men qualified in my final list.

[Powell’s Pals … please note: You can click on the names of each of these individual explorers in the table below for an in-depth review of their lives and their contributions to Powell’s legacy.]

| Name | What They Did | What Was Special About Them |

|---|---|---|

| Clarence Edward Dutton | Rugged field geology work, mapping plateaus, studying earthquakes, researching seismic processes, and volcanism. | Romantic writing, vivid descriptions, passion for the landscape. Land formation theory (isostasy) and sciencific ethics. |

| Clarence Rivers King | Organized and led major surveys; first Director of USGS; mapped vast, unsettled lands beyond the settled Mid-West. | Strong formal training; administrative strengths; public explorer; big vision for mapping vast regions of America. |

| Charles Doolittle Walcott | Chief paleontologist at USGS; discovering and studying fossils (e.g. Burgess Shale), building huge fossil collections; leadership at USGS & Smithsonian. | Great organizer and specimen collector; long institutional leadership; criticism later in life for forcing fossils into pre-existing taxonomies. |

| William John McGee | Melding geology, ethnology, with public science; studies environmental issues and policy causes; studies of loess & fault movement; conservation advocate; editor & institution builder. | Interdisciplinary scientist: collector and organizer; his discoveries changed how people saw ancient life; strong public lands and public policy advocate. |

| Cyrus Thomas | Insect studies; archaeologically significant mounds – mapping and analysis; Indigenous pre-colonial cultures; synthesis of natural history and ethnology. | Worked often in social/cultural sciences; bridged biology and culture; challenged popular myths about Indigenous history and heritage. |

| Gifford Pinchot | First chief of US Forest Service; conservation & political action; scientific forestry; conservation ethic; managing natural resources: public land, air, water, and forests. | Policy-maker; overtly political in state and federal policy; broadly conservative; pushed science into laws & land management; clashed with business & political pressures; legacy of praise and controversy at every turn. |

| Othniel C. Marsh | Major force in fossil discoveries, dinosaurs, and taxonomy; building fossil collections of dinosaur species, mammals and birds; curator of Yale Peabody Museum. “Shelter of science” for Powell and his researchers. | Enormous output; fierce rivalry with Edward Cope; strong institutional power and financial leverage (Peabody); controversial fossil collection practices. |

| James Constantine Pilling | Native-American languages: compiling exhaustive bibliographies of Indigenous languages; proofing and editing major surveys and reports; chief clerk of Bureau of Ethnology; archival/library work. | Quiet work, extremely thorough; huge “behind the scenes” influence; made sure linguistic and cultural traditions were not lost in speed to modernize. |

| Garrick Mallery | Sign language, pictographs, non-verbal communication; gesture systems; researched Indigenous gestures, sign systems; major illustrator of Native American volumes; worked with deaf for gestures across cultures. | Bridged visual culture with non-verbal, symbolic systems and anthropology; blending scholarly rigor with outreach and presentation; revealing what isn’t always said but shown. |

Shared Threads among the Team

- Passion for the Unknown: Whether it was canyons, river systems, fossils, Indigenous languages or cultures, volcanoes, or insects, they all pursued what had not been adequately known or documented before their writings were published.

- Commitment to Frontier / Field Science: Many of them spent extensive time in the field — mapping plateaus and mountains (Powell, Dutton, King), fossil-hunting (Marsh, Walcott), seismology studies (King, Dutton), surveying off beaten paths (Powell, King) — and their scientific contributions often depended on those difficult expeditions.

- Institutional Anchors: Almost all were heavily involved with major scientific institutions — USGS, Smithsonian Institute, Harvard University, Yale’s Peabody Museum, Biltmore’s Forestry School, Yale Forestry School, professional societies and bureaus (GSA, National Academy of Sciences, Bureau of Ethnology, Bureau of Entomology). These institutions provided funding, prestige, oversight, and often defined what “legitimate” science was.

- Publication, Taxonomy, Topography and Description: A core part of their work was describing new species / geological features / fossil catalogues / landscape images; producing maps, ethnographic monographs, government reports; classifying the natural world. Marsh (vs Cope) and Walcott especially in paleontology, Dutton and King in geological mapping and volcanic / seismic features, Thomas & Mallory with ethnological / archaeological description. They all produced substantial written records that shaped future research.

- Influence of Educational and Social Networks: Many had formal training (e.g. King, Marsh, Pinchot) or strong mentorship / support (Marsh via his uncle, George Peabody; Dutton via Yale College). Others were largely self-educated or learned via field experience (Powell, McGee, Thomas), but all were embedded in networks of correspondence, societies, and surveying parties.

- Public / Policy Overlap: Their work did not stay purely scientific. Some engaged in policy (Powell and Pinchot strongly so; McGee and Marsh to some degree), conservation, or public perception of science. Their discoveries and maps had political, economic and cultural consequences.

What Sets These Men Apart — The Key Contrasts

- Explorer vs Archivist: Some were always out in the field (Dutton, Marsh, King, Thomas), others worked on catalogues mostly in archives and libraries (Pilling, Mallery).

- Style of Recognition: Some are household names (Powell, Marsh, King, Pinchot, Walcott); others quietly foundational, less celebrated even if their work mattered deeply.

- Scientific Domain & Interests: Fossils, geology, conservation, languages, culture, sign systems — different gifts and different foci.

- Leadership and Power: Some held major offices, had large projects and had political sway (Powell, Pinchot, Marsh, Walcott); others contributed in narrower but important ways.

- Ethics, Rivalries, Public Memory: There were many with conflicts (Powell vs Hayden, Marsh vs Cope & Pinchot vs Muir), issues of who owns fossils or stories; biases in how Indigenous cultures were treated; modern re-assessments of what was done well and what was flawed.

What We Learn from Powell’s Tight Circle

- Science doesn’t happen in isolation. Adventure, politics, economics and personal drive all matter.

- Sometimes the quietest work (compiling languages, recording non-verbal signs) matters longer and becomes more consequential than the loudest discoveries.

- Powell’s idea — that the land and its people are interwoven — found support in the people who saw the Western territory as more than just rocks or rivers.

- Recognition is unpredictable: what people remember about someone often depends on their public charisma, institutional power or spectacular finds. But real influence also comes from persistence, accuracy, and care for your subject matter.

- The past isn’t perfect. Some practices now look questionable: how fossils were collected or claimed, how cultures were represented. But understanding those flaws helps us honor the good research and finding, and learn from the bad.

My Take: Why Powell’s Pals Are Inspiring

What strikes me about Powell’s colleagues is the wide variety of men in his orbit. Powell didn’t seclude himself in an echo chamber. He explored with fossil hunters, humanists, cataloguers, bureaucrats and activists. These were rough and tumble men, who loved dust and danger; they were people who passionately loved adventure, books and bones.

Some of Powell’s “Pals” are famous because of specialization — Marsh with dinosaurs, Pinchot with forests, Dutton with canyons, Walcott with fossils, Thomas with archeology and insects. Others are less well known — Pilling’s language work, Mallery’s gesture systems — but those quieter works are often what last, in unexpected ways.

Powell’s own strength, it seems, was that he held space in his universe for colleagues who knew more than he did, and who were bold and meticulous in their efforts. They collectively made loud discoveries, painted in vibrant color and were careful record-keepers. That precision is why studying all his Pals together feels like looking at a tapestry: each thread might look small and discrete on its own, but together they form a broad and diverse cloth that is rich and lasting.

References / Addendum for Comparing Powell’s Pals

[1] The members of the 1869 Powell expedition down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon were:

- John Wesley Powell, trip organizer and leader, major in the Civil War

- Andrew Hall, Scotsman, the youngest of the expedition

- John Colton “Jack” Sumner, hunter, trapper, soldier in the Civil War

- William H. Dunn, hunter, trapper from Colorado

- Walter H. Powell, captain in the Civil War, John’s brother

- George Y. Bradley, lieutenant in the Civil War, expedition chronicler

- Oramel G. Howland, printer, editor, hunter

- Seneca Howland, soldier who was wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg

- Frank Goodman, Englishman, adventurer

- W.R. Hawkins, cook, soldier in Civil War

[2] Below are some of key resources. This bibliographical list doesn’t cover everything, but it shows enough so that someone else can check the facts, discover another set of force fields or see where the salient ideas may lead them to new insights.

- Dutton, Clarence. Report on the Geology of the High Plateaus of Utah. U.S. Geog. and Geol. Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, vol. 32, 307 pp. and atlas. 1880.

- Dutton, Clarence. Earthquakes, in the light of the new seismology. US Geological Survey, 1904.

- King, Clarence Rivers. Systematic Geology: The Fortieth Parallel Survey. Government Printing Office, 1878.

- King, Clarence Rivers. Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. Nebraska Press, 1872.

- Mallery, Garrick. Picture-writing of the American Indians. Government Printing Office, 1894.

- Marsh, Othniel Charles. Dinosaurs of North America. Yale University Press, 1896.

- Marsh, Othniel Charles. Introduction and Succession of Vertebrate Life in America: An Address Delivered Before the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Nashville, Tenn, August 30, 1877. Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1878.

- McGee, William John. The Geology of Chesapeake Bay. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1888.

- McGee, William John. Soil Erosion: A National Menace. U.S. Bureau of Soils, 1911.

- Pilling, James Constantine. Proof-sheets of a Bibliography of North American Indian Languages. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 1, Government Printing Office, 1885.

- Pilling, James Constantine. Bibliography of the Algonquian Languages. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 13, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1891.

- Pinchot, Gifford. Breaking New Ground. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1947.

- Powell, John Wesley. Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1878.

- Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. 1st Bison Book ed., University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

- Thomas, Cyrus. Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology for the Year 1891–1892. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1894.

- Thomas, Cyrus. The Mound Builders: Archaeological Essays. U.S. Bureau of Ethnologies, 1894.

- Walcott, Charles Doolittle. Burgess Shale Fossils. Smithsonian Institution, 1917.

- Walcott, Charles Doolittle. Cambrian Trilobites of the Walcott-Rust Quarry. Smithsonian Institution, 1924.

- Walcott, Charles Doolittle. Nomenclature of Some Post Cambrian and Cambrian Cordilleran Formations. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collection. Vol. 67. Frances Wieser (illustrations). Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, MD: Smithsonian Institution and The Lord Baltimore Press, 1924.

- Walcott, Charles Doolittle. “Notes on some sections of trilobites from the Trenton limestone”. 31st Annual Report New York State Museum Natural History (1879): pages 61–63.

- Worster, Donald. A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell. Oxford University Press, 2001.