Witness Post: Commercial Credit Corp.

Commercial Credit Corporation (CCC) was founded in Baltimore, Maryland in 1912 by Alexander E. Duncan and a group of eight businessmen.[1] The company initially lent money to companies using their accounts receivable as security. In 1916 the firm branched out of commercial financing and entered the growing field of auto finance. That bold step represented the firm’s greatest business segment for growth until the 1930s, when the Great Depression caused auto sales to plunge. During the Depression, the firm bought several factoring companies (service providers that buy accounts receivable at a discount from banks and then collect the outstanding monies on those assets). CCC later consolidated these factoring companies under the name Textile Banking Co., Inc.

Alexander E. Duncan, Baltimore, Maryland (1888-1965)

Commercial Credit Corp then bought the American Credit Indemnity Co. of New York, which insured accounts receivable against customer default or bankruptcy. It continued its move into insurance by buying Calvert Fire Insurance, a casualty company that covered physical damage to autos and appliances it was financing. These acquisitions helped CCC win financing business with auto dealers, since the dealers hoped to gain business repairing Calvert-insured cars.

A paperweight from The American Credit-Indemnity Co. of New York

The credit controls and decline in auto manufacturing during World War II badly pinched CCC’s business. To help generate income, the managers at CCC bought several companies that were making money from war-related demands. They diversified their offerings into manufacturing products ranging from pork sausages to printing presses. Competitors like CIT Financial Corp. also diversified into manufacturing during the war. But unlike CIT, CCC held onto its manufacturing operations when the war ended and its finance business became stable again.

Calvert Fire Insurance Co.

By the late 1950s CCC was the largest commercial finance company in the US with annual volume at nearly $1 billion at 10% to 15% interest. But despite the rising volume of the consumer credit business, CCC was becoming less profitable. Competition had become cutthroat, and that fact, combined with the rising cost of capital, was hurting profits. Auto financing remained the core of the firm’s business, at over 50% of its receivables. However, the automotive industry was notoriously cyclical, and CCC was up against giants such as General Motors Acceptance Corp (GMAC). To broaden its appeal, the firm began moving into the leasing of farm equipment, boats, trucks and autos, as well as the financing of these commercial and personal loans.

General Motors Acceptance Corporation – GMAC

In the mid-1950s, the commercial finance unit of CCC was financially hurt. The company managers decided to diversify again, this time the strategy was to stay closer to its primary businesses. In 1956 it bought Dearborn Motors Credit Corp.—a financier of Ford tractors—from a group of Ford executives. CCC renamed the corporation Commercial Credit Equipment Corp. and began financing a full range of industrial farm equipment. In 1958 it started a national drive to get financing business from boat dealers and manufacturers, and the following year it bought the long-term auto leases of Greyhound Rent-A-Car.

In the mid-1960s CCC’s fortunes once again took a turn for the worse. Textile Banking lost $25 million in 1965 due to weak businesses it had bought earlier in the decade. And interest rates soared. The firm was vulnerable to these fluctuations in interest rates because it acquired a large proportion of its funds through short-term borrowing. Notwithstanding these hurdles, the firm earned $25.4 million in 1965 on sales of $307.4 million. (In 1966 CCC had to pay $14 million more in interest than they had paid the year before.) In 1966 CCC’s ten manufacturing companies had $170.7 million in sales, but profits of only $215,000. That year the company named Bertold Muecke as chairperson. Muecke quickly revamped Textile Banking’s management by selling off its unprofitable businesses.

By 1967 CCC had about 1,000 offices across the US and almost $500 million in outstanding personal loans. It had become the third-largest personal loan firm, behind Household Finance and Beneficial Finance, with over $3 billion in total assets and more than $2 billion in life insurance policies in force. Although the firm had plenty of cash, its stock was doing poorly, making it a tempting takeover target. Loews Theatres Inc. quietly began buying CCC stock on the open market. In April 1968, when it had acquired a 10% stake, Loews announced a takeover attempt of the company. The CCC board rejected the offer, but had its back against the wall. The board began looking for a desirable merger candidate. After talks with several companies, CCC agreed to merge with Minneapolis-based Control Data Corp. Loews initially vowed to fight the merger, and a public fight ensued. After months of haggling, Control Data eventually won. CCC received Control Data shares worth $582 million.

Control Data at the time was much smaller than the acquiring CCC, earning $8.4 million in 1966 with only $350 million in assets; however, CCC was already financing and leasing computers, and Control Data had big plans to open a worldwide network of computer data centers, as well as selling and leasing its computers. Control Data lacked the capital for this plan, and the two companies hoped they could be of mutual benefit from the financial synergies generated by the combined companies. In the acquisition CCC was expected to contribute significant capital to the deal, as well as to assist in the leasing and timesharing of computer operations around the US.

CCC generally maintained a low profile during its years under the ownership of Control Data. The firm consolidated its leasing units in 1970 and formed a real estate finance unit the following year. In 1974 CCC formed an insurance division and looked to go international with its insurance products. It bought 70% of France’s Credit Fran£ais and formed a joint venture with Japan’s Nippon Shinpan, a major consumer finance company. Beginning in the late 1970s the firm made a number of acquisitions including Gulf Insurance in 1976 and Great Western Loan & Trust in Texas in 1977. In 1981 CCC bought the Electronic Realty Association (ERA), a real estate franchising network.

Meanwhile the business relationship between CCC and Control Data was eroding. Computers became rapidly less expensive and more powerful in the 1970s, and many corporations that had previously leased mainframes from Control Data began to buy their own computers and to service and maintain them in-house. As this trend intensified, Control Data no longer needed CCC to help it with leasing. CCC also attempted to expand its offerings into a wide area of financial services, starting with banking and savings & loans. CCC opened a national bank based in Delaware, two state-chartered banks, and two savings and loans. These institutions offered mortgages, credit cards, and a variety of other financial services. CCC owned 21% of midsize brokerage Inter-Regional Financial Group Inc. Its business financing expanded to include vehicle and airplane leasing as well as life and casualty insurance. It lent a total of $577 million to foreign countries, about half of them in Latin America. Because of Control Data’s large losses in the computer business, CCC soon lost its investment-grade credit rating, forcing it to pay higher interest rates and a lot more cash for its borrowed money.

Control Data used CCC resources to help it open a network of over 100 business centers, which offered data processing, consulting, and commercial loans to small businesses. The centers were expensive to run, consuming more than $100 million in the three years between 1983 and 1985. In late 1984 CCC began closing the centers. It also transferred its ERA real estate brokerage unit to Control Data and began phasing out withdrawals at some of its savings and loans. This move caused a run at several of its Rhode Island offices. As a result of these problems, CCC had a meager 6.7% return on equity in 1984, half the industry average. CCC had become a drag on Control Data’s earnings. In late 1984 Control Data tried to sell CCC but found no financial takers.

By 1985 the executives at CCC were forced to sell more of the company’s peripheral businesses in order to pay down its swelling debt load. Quickly thereafter, the company began regaining its health, earning about $80 million in 1985 on revenue of about $1.1 billion by year end. The firm had $5 billion in assets at the time.

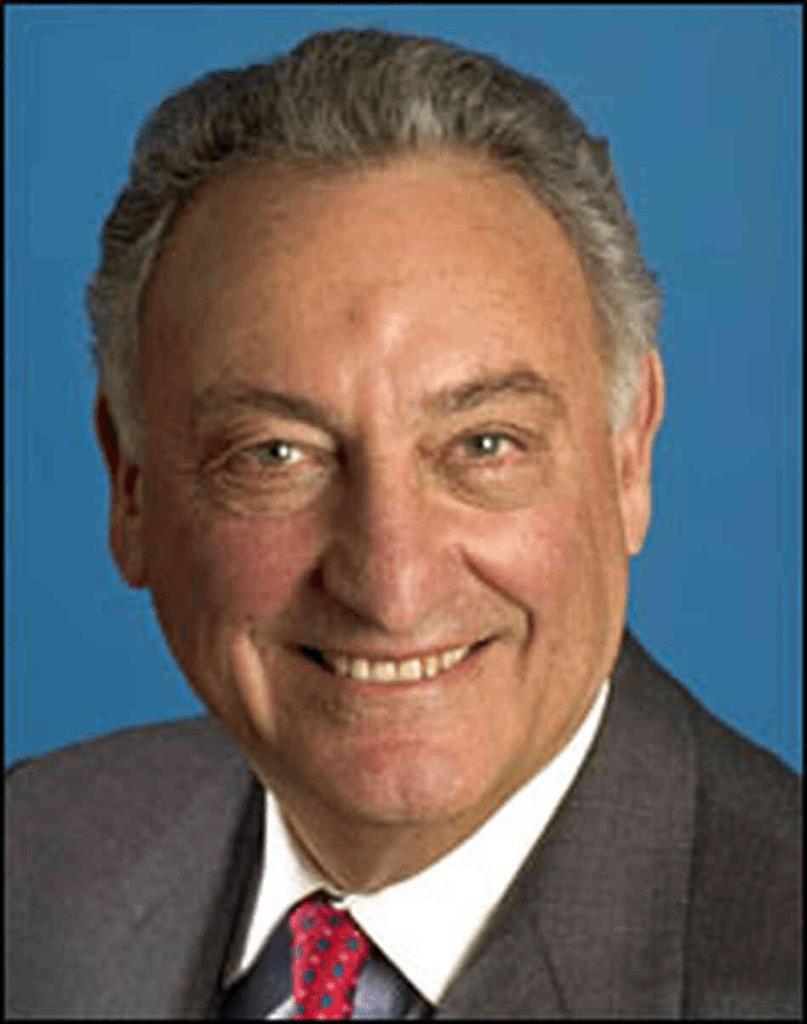

In 1986, CCC internally recruited Robert Bonnell, an experienced insurance executive with American Health and Life Insurance Company (owned by CCC), to take another run at separating CCC from Control Data Corp.[2] Bonnell concentrated his efforts on selling the enterprise to one the best known public company stewards. In September 1986, with the encouragement and invitation of Bonnell, Sanford I. Weill agreed to step in and became chair and chief executive of Commercial Credit Corp, based in Baltimore, Maryland. The marriage was quick as Weill sized up and fixed many of the CCC financial leaks.

Sanford I. Weill

Sandy Weill was a well-known figure on Wall Street at the time. He had built the securities giant Shearson Lehman Brothers and had been elected president of American Express Co. He had resigned from American Express in 1985 and next attempted to become the CEO of BankAmerica Corp, but he was rebuffed. Weill was in search of a position at the helm of an emerging juggernaut, and Bonnell presented the perfect launch pad.

After intense negotiations, Control Data finally agreed to reduce its stake in CCC to about 20% while Weill and other CCC executives bought 10% of the publicly held shares. The remaining 70% was sold to investors in a public stock offering. The total purchase of CCC for Weill and team was approximately $7 million.

As the new captain of the Commercial Credit, Weill brought with him a group of experienced finance executives. He paid these executives less than they had earned elsewhere on Wall Street, but rewarded them handsomely with CCC stock. The new management team quickly went to work examining the vast collection of CCC businesses. The team took out a hatchet to some of the CCC divisions: they sold off the businesses in life insurance, vehicle leasing, and overseas lending. Within just one year, CCC tripled its operating profits. In September 1987, CCC bought back Control Data’s remaining stake for $22 per share using cash on its balance sheet.

In 1988 Weill used the rejuvenated Commercial Credit as a springboard to a shopping spree. CCC’s largest purchase was Primerica Corp, the parent company of Smith Barney and the A.L. Williams insurance company. To finance the deal Primerica’s stockholders were offered CCC shares on a one-for-one trade basis. Because of a difference in dividend yields, Primerica holders were also offered a one-time $7.00 per share cash dividend. The total purchase price was $1.54 billion. Weill insisted on keeping operating control, so although Primerica owned 54% of the new company, they held only four of 15 seats on the board of directors. Technically, CCC was the buying company, however, the Primerica brand was kept as the name of the new company. In the deal CCC became a Primerica subsidiary, and it emerged as the leading component of Primerica’s consumer services division. CCC’s 1988 profits were $161.8 million on sales of $943.7 million, for a 17% operating margin.

In 1989, Weill acquired all of Drexel Burnham Lamert’s retail brokerage outlets. And in 1992, Weill agreed to pay $722 million to buy a 27% share of Travelers Insurance, which had gotten into deep trouble with some bad real estate investments.

By 1989 CCC had 490 offices in 29 states and $3.4 billion in receivables. Weill continued to make changes to strengthen its financial performance, tightening underwriting criteria and monitoring loans through more sophisticated financial systems. Greater emphasis was placed on collecting loans and resolving problems. In April 1989, Primerica acquired Action Data Services, a data processing supplier. The transaction was partly for Primerica to perform in-house data processing. In late 1989 for a price tag of $1.35 billion, CCC acquired the branch offices and loan portfolio of Barclays American Financial. Barclays, based in Charlotte, North Carolina, was a branch of Britain’s Barclays Bank PLC that specialized in consumer loans and home equity lending. The acquisition, which brought 220 offices in 29 states and $1.3 billion of receivables, was seen as increasing CCC’s loan portfolio by 40 percent at a reasonable price. While Barclays’ offices that overlapped with CCC’s were closed, the purchase brought CCC back into the western states of the US, which it had abandoned during the consolidation of 1985. The firm had about $190 million in profits for the year.

In 1991 CCC bought Landmark Financial Services Inc., the consumer finance branch of MNC Financial, for about $370 million. By the end of 1992 CCC had 695 branch offices in 39 states and was planning to open 50 more offices during the next year. Newer offices were being opened with staffs of only two or three, versus four or five for older offices, and used one-third less space. These and other cost control efforts had brought operating expenses down to 4.28% of average receivables. The branch office network used a goal system that encouraged managers to treat their offices like their own businesses, giving them control over revenues and expenses. Because they were more aware of the conditions of a local economy, they were given flexibility in determining if customers met CCC’s credit requirements. Top performing managers were rewarded with large cash bonuses.

In 1993 CCC introduced a new computer-based branch information system called Maestro. The system automated point-of-sale marketing and credit evaluations, allowing branches to quickly determine which products a given customer was qualified for. Prior to that time, customer data was written on forms and credit checks were done by telephone and mail. [3]

Interestingly the resurgence of Sandy Weill was profound. In 1993, like a shadow of corporate revenge, Weill reacquired his old Shearson brokerage from (now Shearson Lehman) from his former employer, American Express for $1.2 billion. By the end of the year, he had completely taken over Travelers Corp. in a $4 billion stock deal. The combined conglomerate was officially named Travelers Group, Inc.

Because Weill believed that scale mattered in the insurance business, in 1996 he added the property and casualty operations of Aetna Life & Casualty to Traveler’s holdings at a cost of $4 billion. Continuing his buying spree, in September, 1997, Weill acquired Salomon Inc., the parent company of Salomon Brothers, Inc. for over $9 billion in stock. The new enterprise was dubbed Citigroup, Inc. with Weill serving as Chair.

Thus ends the long and windy 85-year saga of Commercial Credit Corp. (CCC) formerly based in Baltimore, Maryland.

[1] https://www.encyclopedia.com/books/politics-and-business-magazines/commercial-credit-company

[2] Private notes taken by H. Hooper in 1988 after verbal discussions with Bonnell at his personal residence in Baltimore, Maryland. Bonnell was a close friend of my father’s. He claimed to be a key matchmaker in the CCC acquisition, although Weill has reported the story differently (never mentioning Bonnell) in his own personal version of the events.

[3] Although 1993 is 31 years ago, from the date of this Witness Post (July, 2024), the financial thread and CCC story (as a company with separate financials) grinds to a halt, as CCC seems commingled with the parent company Travelers Group, Inc. and then Citigroup. If anyone can help pick up the thread from the past few decades, please let me know.