Powell’s Pals: Gifford Pinchot

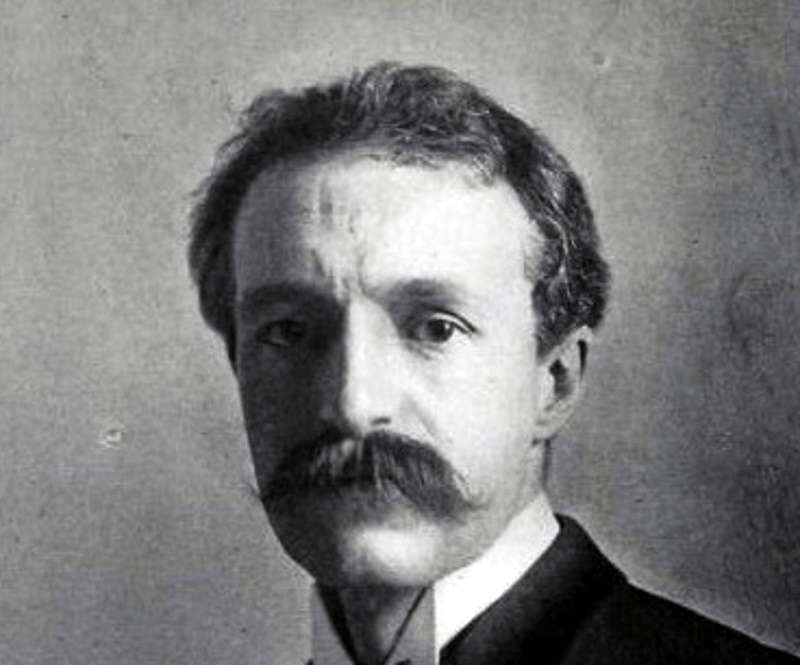

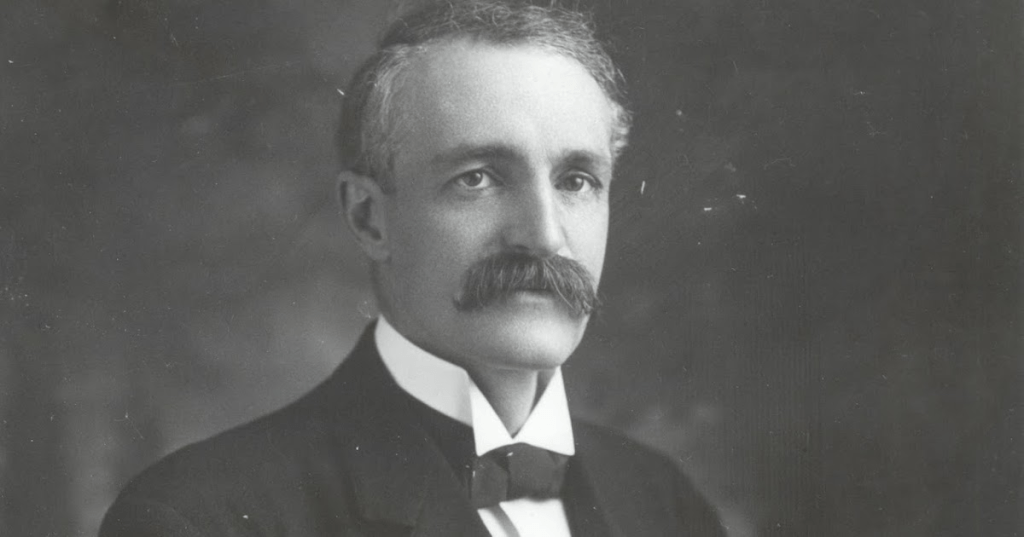

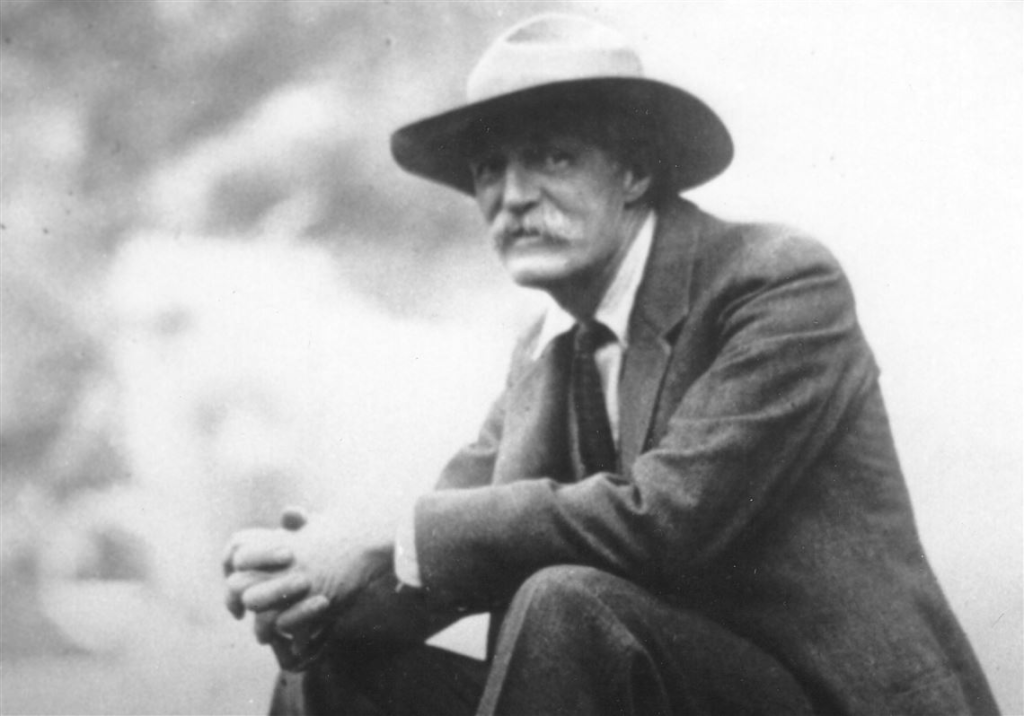

Gifford Pinchot was an American forester and politician. Over his professional and political life, he served in significant national and regional roles. He was the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, the first head of the United States Forest Service, and the 28th governor of Pennsylvania. He served for two terms as Governor of the Keystone state. Pinchot was a conservative flagbearer as a member of the Republican Party for most of his life, though for a brief perion he joined the Progressive Party. [1]

Pinchot’s prominence in politics and in the machinations of Washington, D.C. was demonstrable. He also maneuvered in various state capitols with ease, which differed from the skillset of John Wesley Powell. And, although Powell and Pinchot knew each other and worked on the lands beyond the 100th Meridian at the same time, their work can be considered “parallel play.” Their visions of the forest were aligned but not in the same dimension. As the author Wallace Stegner puts it, “Powell would be applying through that same corporate instrument [government cash] a good many checks to the greed that was gobbling the West ... [and behind Powell’s efforts] was Gifford Pinchot with a coherent plan of conservation and a bureaucratic aggressiveness and daring even greater than Powells.“[4]

Feud with John Muir

One of the matters to address early in this Powell’s Pals post is the fierce clash between Gifford Pinchot and naturalist John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club. Although they originally shared a professionally cordial relationship, their philosophies eventually tore them apart. Muir came to think of Pinchot as the embodiment of everything he opposed: the view that forests and rivers existed primarily to serve the needs of human kind. Pinchot preached “the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run,” strongly advocating scientific management of timber, dams to control water, and contouring of the land. Muir, on the other hand, believed in nature for its own sake—sacred and untouchable; it was to be preserved whole, pristine, without human intervention.[6]

This battle of ideas came to a head in the fight over damming the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite. In the aftermath of the massive 1906 earthquake and fire in San Francisco, [7] the state of California vowed never again to have so little water available to save the city, so they proposed a dam on the Tuolumne, creating a reservoir to combat future calamities. Pinchot was in favor of the dam, as a safeguard for San Francisco. Muir was against the dam and spoke passionately to Congress many times espousing his belief that the entire landscape and every river valley should be preserved. Heralded as a “Little Yosemite Valley” carved out by the Tuolumne River, the Hetch Hetchy Valley was adjacent to Yosemite and in the same ecosystem as the larger park preserve. Muir poured his waning strength into the campaign to Stop the Damn Dam, and he lost. To Muir the loss was devastating and life altering. Although Muir actually died of pneumonia, in Los Angeles in 1914, many of his friends and family felt the heartbreak of watching Hetch Hetchy Valley drowned in the backwater of the Tuolumne was what truly broke his spirit.[6]

And herein lies one of the Pinchot ironies: Muir Woods National Monument, outside San Francisco, has a rock whose inscription by the Sierra Club dedicates a tree to Gifford Pinchot. One can imagine Muir bristling at the thought of this recognition, which was made 4 years before his death—but perhaps there was grudging respect for his old adversary after all. Then again, the gesture of assigning Pinchot a single tree amid a vast monumental grove of redwoods may be the sharpest commentary of all. It is no accident that Yosemite National Park itself — Muir’s cathedral — has no such reference to the Pinchot name or legacy.[6]

Early Life, Family Connections & Education

Gifford Pinchot was born in Simsbury, Connecticut, in 1865. He was named after Sanford Robinson Gifford, who was a recognized Hudson River School artist. Pinchot was the oldest child of James W. Pinchot, a successful New York City interior furnishings merchant, and Mary Eno, daughter of one of New York City’s wealthiest real estate developers, Amos Eno. James and Mary Pinchot were both integrated with prominent Republican Party leaders and former Union generals, including family friend William T. Sherman. Beyond the nuclear family, Pinchot’s paternal grandfather had migrated from France to the United States in 1816, becoming a merchant and major landowner based in Milford, Pennsylvania. His mother’s maternal grandfather, Elisha Phelps, and her uncle, John S. Phelps, both served in Congress. Pinchot had one younger brother, Amos, and one younger sister, Antoinette, who later married British diplomat Alan Johnstone. Those deep family positions of prominence, which ooze with privilege, would frequently aid Pinchot’s later political career. [1]

Pinchot was educated at home until he was 16, when he enrolled in the elite private school, Phillips Exeter Academy. He then matriculated at Yale College in 1885. His father made conservation a Pinchot family affair and suggested that Gifford become a forester. James Pinchot asked, just before Gifford left for college, “How would you like to become a forester?” At Yale, Pinchot studied science, played on the football team, was “tapped” as a member of the secret society, Skull and Bones, and volunteered with the YMCA. The 1888 Yale football team were national champions that year, and Pinchot scored two touchdowns in the last game, earning him a varsity letter. The team was coached by the legendary Walter Camp, and was both undefeated and unscored upon that season.[3]

After graduating from Yale in 1889, Gifford Pinchot took his father’s advice and embarked on a career in forestry. He traveled to Europe, where he met with leading European foresters at the time. These foresters suggested that Pinchot continue his studies in the French forestry system and encouraged him to apply to the National School of Forestry in Nancy, France. This understory is where his formal, broad plant system studies took place, and where he learned the basics of forest economics, law, and science. Pinchot returned to America after thirteen months in France, and, against the advice of his professors, decided not to complete his studies in the French curriculum. Pinchot felt that additional training was unnecessary. What mattered more was quickly getting the profession of forestry started in America.[1]

Open for employment, Pinchot landed his first professional forestry position in 1892, when he became the manager of the forests at George W. Vanderbilt II‘s Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. The following year, Pinchot met the naturalist, John Muir, who founded the Sierra Club. Muir would become Pinchot’s mentor and, later, his rival. Pinchot worked at the Biltmore Estate until 1895, when he fell out with the estate’s lead forester, Dr. Carl Schenck, and was fired. Pinchot left North Carolina and opened his own forestry consulting office in New York City.[1]

In 1896, Pinchot embarked, as the only forester on a tour of the American West with the National Forest Commission, which lasted for about a year. He had strong disagreements with the commission’s final report, which advocated preventing U.S. forest reserves from being used for any commercial purpose; Pinchot instead favored the development of a professional forestry service which would preside over limited commercial activities in forest reserves. Despite the series of disputes with men in power, including Carl Schenck and the authors of National Forest Commission report, in 1897 Pinchot was appointed as a special forest agent for the United States Department of the Interior.[1]

One year later, in 1898, President William McKinley appointed Pinchot as the head of the Division of Forestry, and Pinchot became the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), which was officially established in 1905. Pinchot enjoyed a close relationship with two consecutive presidents — McKinley and Roosevelt. President Theodore Roosevelt shared Pinchot’s views regarding the importance of conservation. Pinchot’s main contribution was his leadership in promoting scientific forestry and emphasizing the controlled, profitable use of forests and other natural resources so they would be of maximum benefit to mankind. He coined the term conservation ethic as it applied to the nation’s natural resources.[1]

More Trees and More Yale

In 1900, Pinchot established the Society of American Foresters, a ‘turn of the century’ organization that helped bring credibility to the new profession of forestry. The Society was part of the broader reach for professional forestry, a movement that was underway in the U.S. The Pinchot family, driving the conscious need for forest professionalism, endowed a 2-year graduate-level School of Forestry at Yale University, which is now known as the Forest School at the Yale School of the Environment. At the time it became the third school in the U.S. that trained professional foresters, after Cornell’s Forestry School in New York and Biltmore’s School in North Carolina. Central to his publicity and advocacy work was the creation of news for magazines and newspapers, highlighting forestry.[1]

With Pinchot’s help, President Roosevelt called for the creation of millions of acres of federal forests. In short order the two mapped out the boundaries of 16 million acres of new National Forests (which became known as the 1907 “midnight forests“). The president’s action took place just minutes before he lost the legal power to do so. Despite congressional opposition, Roosevelt, Pinchot, and Secretary of the Interior James R. Garfield continued to find ways to protect public land from private development during Roosevelt’s last two years in office. Pinchot hand-picked William Greeley, son of a Congregational clergyman, who finished at the top of that first Yale forestry graduating class of 1904, to be the Forest Service’s Region 1 Forester. Greeley was given the responsibility over 41 million acres in 22 National Forests, in four western states (all of Montana, much of Idaho, Washington, and a corner of South Dakota).[1]

Back Out of Politics and a New Party

After fellow Yalie William Howard Taft succeeded Roosevelt as president in 1909; Pinchot’s forest favoritism faded. The politics that followed was local and personal. Pinchot was embroiled at the center of the Pinchot–Ballinger controversy, a dispute with Richard Ballinger, Taft’s pick as the Secretary of the Interior. Pinchot accused Ballinger of criminal behavior by helping an old client of his gain territorial water rights and thus promoting big business. In the dispute, Taft favored Ballinger and Roosevelt favored Pinchot. That controversy led to Pinchot’s dismissal, his second career firing.[2]

The controversy also contributed to the dramatic split of the Republican Party, with Taft as its standard bearer, and the formation of the Progressive Party, just prior to the 1912 presidential campaign. Gifford Pinchot, W J McGee and other Progressive zealots supported Roosevelt’s Progressive candidacy. On election day Roosevelt and Taft split the conservative votes and both were defeated by Democrat Woodrow Wilson.[2]

Two-Time Pennsylvania Governor

Pinchot returned to public office in 1920, becoming the head of the Pennsylvania’s forestry division under Governor William C. Sproul. He succeeded Sproul two years later by winning the 1922 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election. Pinchot’s victory over his Republican opponents owed much to his reputation as a staunch teetotaler during Prohibition; he was also boosted by his popularity with farmers, laborers, and women. Pinchot focused on balancing the state budget; he inherited a $32 million deficit and left office with a $6.7 million surplus. He won a second term as governor through a victory in the 1930 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, and Pinchot supported many of the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. [1]

Candy is Dandy, but Liquor is Quicker

After the repeal of Prohibition with the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment, Pinchot changed his stripes. Instead of remaining a staunch teetotaler, he advocated that, with his guidance, legal alcohol could flourish in the Keystone State. He led the establishment of the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board, calling it “the best liquor control system in America.” He retired from public life after his defeat in the 1938 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election; however, he remained active in the conservation movement for the rest of his life.[1]

Pinchot’s Personal Life

In the early 1890s, Pinchot fell in love with Laura Houghteling, who lived near him in Asheville, North Carolina. Houghteling was the daughter of a wealthy Chicago lumberman. Pinchot was managing the forest assets of the Biltmore estate, while Houghteling stayed at her family estate Strawberry Hill on the French Broad River. In 1893, they decided to marry, but Laura tragically passed away in early 1894 after a protracted battle with tuberculosis. Gifford Pinchot was wrecked: he wore black mourning clothes in the following years, wrote about Houghteling often in his journal, and did not marry for another 20 years.[1]

During the 1912 presidential campaign, Pinchot frequently worked with Cornelia Bryce, a women’s suffrage activist, who was a daughter of former Congressman Lloyd Bryce and a granddaughter of former New York City mayor, Edward Cooper. They became engaged and were married in 1914. Although Cornelia Pinchot waged several unsuccessful campaigns for the United States House of Representatives, she was successful with numerous other political and public service activities, and has been described by historians at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission as “one of the most politically active first ladies in the history of Pennsylvania.” She gave numerous speeches on behalf of women, organized labor, and other causes, and frequently served as a campaign surrogate for her husband. Pinchot and his family took a seven-month voyage of the Southern Pacific Ocean in 1929, which Pinchot chronicled in his 1930 work entitled, To the South Seas.[1]

Pinchot and his wife had one son, Gifford Bryce Pinchot, who was born in 1915. The younger Pinchot later helped found the Natural Resources Defense Council, an organization similar to his father’s National Conservation Association.[1]

William Greeley and the “Fire Engine Company”

One of the most devastating pieces of legislation and political folly, in Pinchot’s view, arrived at the instructions of William Greeley, his hand-picked candidate to head of the US Forest Service. After a catastrophic forest fire, known as the Fire Storm of 1910, the politics, along with the trees of forests, were ablaze. In 1911 the religiously reared Greeley became convinced that Satan had been at work in the conflagration, and he had an existential change of heart. That fire storm converted him from a land steward into a fire extinguishing evangelist, who elevated firefighting as the raison d’être and overriding mission of the Forest Service. Under Greeley, the USFS became The Fire Engine Company for the US, protecting trees so that the timber industry could cut them down later at government expense.

Pinchot was appalled at the policy shift. The timber industry had successfully re-oriented the Forestry Service toward policies favoring large-scale harvesting via regulatory capture, and metaphorically, the timber industry was now “the fox in the chicken coop.” Pinchot and Roosevelt had originally envisioned, at the least, that public timber should be sold only to small, family-run logging outfits, not to big lumber syndicates. Pinchot had always preached of a “working forest” for working people and small-scale logging at the edge, and tree preservation at the core of the Forest Service’s mission. In 1928 William Greeley left the USFS for a lucrative position in the timber industry, becoming an executive with the West Coast Lumberman’s Association.[1]

When Pinchot traveled west in 1937, nine years after Greeley’s departure, to view those USFS acres with Henry S. Graves, what he saw “tore his heart out.” Greeley’s legacy, combining modern chain saws and government-built forest roads, had allowed industrial-scale, clear-cuts to become the norm in the western national forests of Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon. Entire mountainsides, mountain after mountain, were treeless. “So this is what saving the trees was all about?” “Absolute devastation,” Pinchot noted in his diary. “The Forest Service should absolutely declare against clear-cutting in Washington and Oregon as a defensive measure,” Pinchot wrote.[1]

Eugenics

Another deeply unsettling belief system in the life of Gifford Pinchot was his membership in and contributions to Eugenics: the belief that certain races should have children and others not. How these theories fit into his view of the world is unclear, yet starting in 1912, Pinchot was a delegate to the first International Eugenics Congress. He attended the congress again in 1921, and was elected as a member of the advisory council of the American Eugenics Society, from 1925 to 1935.[5]

The American Eugenics Society organization started by promoting racial betterment, eugenic health, and genetic education. Their tactics consisted of public lectures, exhibits at county fairs, and disbursing propaganda leaflets. To gain popularity the eugenics movement adopted “two faces,” a positive and a negative face. The ‘positive’ face focused on emphasizing the urge for the “genetically gifted” to reproduce. The ‘negative’ face of the eugenics campaign involved efforts to prevent the “defective” individuals from reproducing. This negative side of the movement catalyzed anti-immigration protests of the early twentieth centuries, because of the idea that non-whites and immigrants were “inferior” to “native-born white Americans” in terms of intelligence, physical condition, and moral stature.[5]

To be blunt, Eugenics is and was pure racism. It was adopted in Nazi Germany by Adolph Hitler, the architect of the Third Reich, as a rationale to promote white families and to exterminate Jews. Hitler promulgated his insidious false claims of the supremacy of the Aryan Race across all of Western Europe in the 1930s.

Final years and Autobiography

Out of public office, Pinchot continued his ultimately successful campaign to prevent the transfer of the Forest Service to the Department of the Interior, frequently sparring with FDR’s Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Pinchot was a prolific writer who published new editions of his manual on forestry. He also worked on his autobiography, Breaking New Ground, which was published shortly after his death. During and after World War II, Pinchot advocated for conservation to be a part of the mission of the United Nations, but the United Nations would not focus on the environment or environmental issues until 1972, with the named meeting: United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.[1]

Gifford Pinchot died from Leukemia, a progressive malignant blood disease, in 1946. He was 81. Pinchot is buried in a grave at Milford Cemetery, in Pike County, Pennsylvania.[1]

Pinchot Memorials

According to Wikipedia: Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington and Gifford Pinchot State Park in Lewisberry, Pennsylvania, are named in his honor, as is Pinchot Hall at Penn State University. A large Coast Redwood in Muir Woods, California, is also named in his honor, as are Mount Pinchot and Pinchot Pass near the John Muir Trail in Kings Canyon National Park in the Sierra Nevada in California. The Pinchot Sycamore, the largest tree in his native state of Connecticut and second-largest sycamore on the Atlantic coast, still stands in Simsbury. The house where Pinchot was born belonged to his grandfather, Captain Elisha Phelps, and is also on the National Register of Historic Places. He is also commemorated in the scientific name of a species of Caribbean lizard, Anolis pinchoti. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy accepted the family’s summer retreat house, Grey Towers National Historic Site, which the Pinchot family donated to the U.S. Forest Service. It remains the only National Historic Landmark operated by that federal agency. The street address of the USDA’s Forest Products Laboratory headquarters in Madison, Wisconsin is 1 Gifford Pinchot Drive.[1]

Gifford Pinchot III, grandson of the first Gifford Pinchot, founded the Pinchot University, now merged with Presidio Graduate School. The Pinchot family also dedicated The Pinchot Institute for Conservation, which maintains offices both at Grey Towers and headquarters in Washington, D.C. The Institute continues Pinchot’s legacy of conservation leadership and sustainable forestry.[1]

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gifford_Pinchot

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinchot%E2%80%93Ballinger_controversy

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1888_Yale_Bulldogs_football_team

[4] Stegner, Wallace, Beyond the Hundreth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West, Penguin Books, New York, 1954.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugenics

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Muir

[7] The 1906 San Francisco fire, was caused by the massive earthquake (measuring 7.8 on the Richter scale), from April 18 to April 21, 1906. Approximately 3,000 people lost their lives due to the disaster. The fire destroyed around 28,000 buildings across the city and an estimated 490 city blocks were devastated, leaving over half of the population homeless (~200,000 out of 400,000 residents). The total economic losses were around $400 million at the time, and has been estimated at over $12 billion in 2025.

[8] Gifford Pinchot was one of the men with whom John Wesley Powell found some of his strongest kinship. The exploration of the relationship is outlined and discussed in another Powell’s Pals post on Pinchot and eight other scientists and explorers from the Powell era.