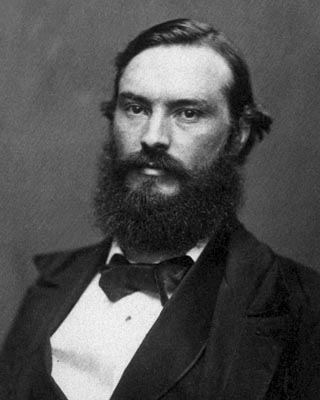

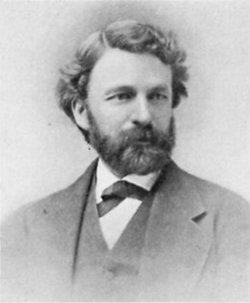

Powell’s Pals: Clarence King

Clarence Rivers King was an American geologist, mountaineer and author. From 1879 to 1881 he was the first director of United States Geological Survey, (USGS). Nominated as director by US President Rutherford B. Hayes, King was best noted for his geological discoveries and writings on the Sierra Nevada mountain range. His life also had an interesting twist at its end that stunned his former colleagues and admirers. King was succeeded as USGS director by John Wesley Powell. [1][6]

King’s Early Life and Education

Clarence King was born on January 6, 1842, the son of James Rivers King and Florence Little King. James King was part of a family firm engaged in trade with China, which kept him away from home a great deal; he died in 1848. That same year, Clarence’s two sisters, Florence and Grace, both died in their early childhood. These family tragedies stranded the young mother to raise Clarence, with the support of her mother, Sophia Little.

Clarence developed an early interest in outdoor exploration and natural history, which he expanded under the tutelage of Rev. Dr. Roswell Park, head of school at the Christ Church Hall in Pomfret, Connecticut. After his early education, Clarence attended schools in Boston and New Haven, before he was accepted at Hartford High School. He was a good student and a versatile athlete of short stature, but unusually strong. At the same time Clarence suffered from adolescent depression, which impacted his self-image and joy of learning. His mother, meanwhile, married George S. Howland in July, 1860, with whom she bore a daugher, Marian. George Howland financed Clarence’s education as he was admitted to the Sheffield Scientific School, affiliated with Yale College, in August, 1860.

Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College

At Yale, King specialized in “applied chemistry” and also studied physics and geology. One inspiring teacher who influenced King was James Dwight Dana, a highly regarded geologist, who had participated in the United States Exploring Expedition, a scientific expedition to the South Atlantic, South Pacific and the west coasts of South and North America. Another was George Jarvis Brush, a noted mineralogist and the first curator of the Peabody Museum at Yale.

Besides Dana and Brush’s academic influences, King was heavily impacted earlier in life by the belief systems of his maternal grandmother, Sophia Little, who disdained slavery. She would not eat fruits and other Southern products because “they were grown with slave labor.” Because of this family bias, King was against slavery and all African American injustice. While at Yale, he was known as an enthusiastic abolitionist and had lots of rage against the Confederates. He aligned with the militant anti-slavery advocates and even considered joining the war efforts to fight for his beliefs.

Besides politics at Yale, King enjoyed playing many sports, but rowing crew was his athletic passion. He joined the crew team and eventually became its captain. The Undine team [2] competed on a four-man boat, with King at the stroke oar. After just two years at Sheffield Scientific School, in July 1862, King graduated with a Ph.B. (Bachelor of Philosophy) in chemistry. That summer, he and several friends borrowed one of Yale’s rowboats for a trip along the shores of Lake Champlain and a series of Canadian rivers, before they returned to New Haven for the fall regatta.

In October 1862, on a visit to the home of professor, George J. Brush, King heard Brush read aloud a letter he had received from William Henry Brewer telling of an ascent of Mount Shasta in California, then believed to be the tallest mountain in the United States. King began to read more and more about geology, he attended a lecture by Louis Agassiz, a Harvard professor of zoology and geology, and he read with fascination tales of mountain climbing in the Alps. King soon wrote to Brush stating that he had “pretty much made up my mind to be a geologist, if I can get work in that direction.“

As to his belief systems around slavery, by the time King graduated from Yale, he had returned to his pacifist ways and renounced his anger against the South. He decided that he would help the nation by exploring and mapping the West for his fellow Americans to later live.

In 1863, King moved to New York City. He shared an apartment with James Terry Gardiner, a close friend from high school and college. King longed to see the mountains of the American West, and his friend, Gardiner, was miserable in law school, so they decided to move together to San Francisco. As Gardiner and King quickly planned their journey, another friend, William Hyde, became interested and asked to join them. The trio agreed and met in April 1863 in Niagara, New York, where they boarded a train west. They deboarded in St. Joseph, Missouri, which they declared was their “starting point.”

Near Fort Kearny, 200 miles into their journey, King tried hunting buffalo alone. The travel party had succeeded in killing two buffalo in Troy, Kansas, so a second attempt seemed doable. King failed in his hunt, ending up with a wounded leg and a dead horse.

The traveling party’s wagon train passed Chimney Rock, Nebraska, and a few days later arrived at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. On June 29, the party crested the ridge of the Wasatch Mountains, Utah to the view of the Great Salt Lake below them, a place of refuge before they began to travel across the desert. By August 6, the wagon train arrived at Carson City, Nevada. Here, King, Gardiner and Hyde decided to leave the wagon train party and to head to the nearby town of Gold Hill. William Hyde’s father owned a ranch and foundry there, and the men set up camp near the foundry.

As fate would have it, that night, the foundry caught fire, burning everything the men owned, including King’s letter to William Henry Brewer at the California Geologic Survey. The three men stayed in Gold Hill long enough to rebuild the foundry. King and Gardiner were able to save up enough supplies to continue their journey. Hyde decided to stay behind with his father. On September 1, the two friends boarded a steamboat heading towards San Francisco. While on the steamboat King met up with Brewer in person and explained to him what happened to the letter. King expressed his willingness to work for the survey without pay. He told Brewer that he liked him personally and knew the survey would be a good experience. Joining the California Geological Survey was the first step in King’s geologic career.

King’s Early Career

Once Gardiner and King arrived at the California Geological Society’s office, they met the director of the survey Josiah Whitney, who was a Yale grad and professor of geology at Harvard. In 1863, with Whitney’s permission, King accompanied Brewer on his exploration of the northern part of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range. As the group traveled, they passed through the Sierra gold fields and alongside streams. At Genesee Creek, Brewer found fossils from the Jurassic or Triassic age. This important find would help them pinpoint the age of the Mother Lode gold belt, which was one of their goals on this journey. Near Lassen Peak in northern California, Brewer and King investigated hot springs and other thermal features, which reeked of sulphur. At nights around the campfire, the party discussed geologic topics such as the young Cascade volcanoes, the age of gold veins, and the action of glaciers. During one of these conversations, Brewer brought up Whitney’s plan to propose a geologic study across the continent, and King thought that there may be a chance of funding the study because, as Whitney had noted, railroad companies would benefit from it.

Upon returning from his first expedition, King immediately began preparing for the next. This time, he was traveling with a mining engineer William Ashburner and a topographer Charles Hoffmann. The assignment was to survey the Mariposa Estate, one of the most important gold-vein regions in the area. The party consisted of Brewer, Hoffmann, Gardiner, King and Dick Cotter. The party used triangulation as their main method of mapping the areas they traveled through. At one point, they reached a spot where the pack animals could not continue, so they prepared a basecamp at an unknown mountain lake. The next day, Hoffmann and Brewer climbed the unknown peak nearby (now known as Mount Brewer), where they discovered that they were not on the main Sierra Nevada Crest, as they thought they were. From that vista point Brewer and Hoffmann identified and named Mount Tyndall, Mount Goddard, and Mount Whitney.

King, upon hearing what Hoffmann and Brewer saw, begged to be allowed to backpack up Mount Whitney with Cotter. In King’s own words, “It was a trying moment for Brewer when we found him and volunteered to attempt a campaign for the top of California, because he felt a certain fatherly responsibility over our youth.” Brewer eventually gave his permission, even though King and Cotter had no real plan. The duo ran short of provisions, before they even made it to the midpoint of Mount Whitney, so they turned back.

King got permission for a second attempt to ascend Mount Whitney, but he had to rendezvous with the main survey group in two weeks at Clark’s Station. King did not end up making it to the top on this expedition either, due to time constraints, which greatly disappointed him. On his way to Clark’s Station, King ran into serious trouble with bandits, but his horse was able to outrun them, saving his life. Both Gardiner and King were unpaid volunteers for this expedition, but they had helped create the first topographic, botanical and geologic survey of this vast area of California.

In September 1864, President Abraham Lincoln designated the Yosemite Valley area as a permanent public reserve. King and Gardiner were appointed by Whitney to make a boundary survey around the rim of Yosemite Valley. Due to various calamities — health concerns (malaria), travel complications (Nicaragua diversion), and deaths (King’s step-father, George Howland, died) — King could not return to the Yosemite project until 1866.

In their down time, King and Gardiner developed a plan for an independent survey of the Great Basin region of the Continent. In late 1866, King used his political muscle and connections and travelled to Washington, DC, to pitch his survey. His list of influential friends and acquaintances were a plus in his favor. [4] He wanted to secure funding from Congress for such a survey and he tactfully used his connections.

Fortieth Parallel Survey and The Diamond Hoax

King made a persuasive pitch to the congressmen and senators and chartered federal funders. Leaning on railroad business interests, he argued that his research would help “develop the West.” With those magic words, he was successful in his plea and received federal funding. In the process King was named U.S. Geologist of record for the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, in 1867, commonly known as the Fortieth Parallel Survey. King persuaded Gardiner to be his second in command and they assembled a team that included, Samuel F. Emmons, Arnold Hague, A.D. Wilson, photographer Timothy O’Sullivan, James D. Hauge, artist Gilbert Munger and others. Over the next six years, King and his team explored areas from eastern California to Wyoming. During that time he also published his famous journal Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada (1872).

While King was finishing the Fortieth Parallel Survey, citizens in the western U.S. were abuzz with the rumors of a secret diamond deposit somewhere in the region. King and some of his crew tracked down the secret location in northwest Colorado and exposed the deposit as fraudulent. Now known as the Great Diamond Hoax of 1872, by exposing the hoax, King became an international celebrity.

In 1878, King published Systematic Geology, numbered Volume 1 of the Report of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, which completed his seven volumes of survey materials. In this work he narrated the geological history of the West as a mixture of uniformitarianism and catastrophism. The book was well received at the time and has been dubbed as “one of the great scientific works of the late nineteenth century.”

The Creation of the USGS

In 1879, the US Congress consolidated the number of geological surveys exploring the American West and created the United States Geological Survey (USGS). King was chosen as its first director. He took the position with the understanding that it would be temporary, and he reported to Washington, DC to command his post. He resigned as director after twenty months, having overseen the organization of the new agency with an emphasis on mining, mapping and geology. President James Garfield named John Wesley Powell as King’s successor.[3]

During the remaining years of his life, King for the most part withdrew from the scientific community and attempted to profit from his knowledge of mining geology. However, the mining ventures he was involved in were not successful enough to support his lifestyle. Over the years he had acquired expensive tastes in art collecting, travel and elegant living, and he went heavily into debt. He had a busy social life, with close friendships including Henry Brooks Adams and John Hay, who admired him tremendously. But he suffered from physical ailments and his adolescent bouts of depression re-emerged in his later life.

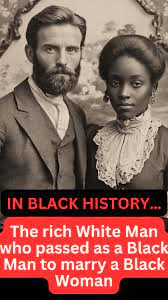

Common Law Marriage and Passing as African-American

Ebony & Ivory

According to family records and later research [4], King spent his last thirteen years in and out of obscurity. He was leading a double life. In 1887 or 1888, he met and fell in love with Ada Copeland, an African-American nursemaid and former enslaved woman from Georgia. Copeland had moved to New York City in the mid-1880s and soon lived with King. As inter-racial marriages were strongly discouraged in the nineteenth century, and illegal in many states, King hid his identity from Copeland and many others. Despite his blue eyes and fair complexion, King convinced Copeland that he was James Todd, an African-American employed as a Pullman porter.

Copeland and King entered into a common law marriage in 1888. Throughout the marriage, King never revealed his true identity to Copeland, pretending to be Todd, a Black railroad worker, when at home, and continuing to work as King, a white geologist, when in the field. Their union produced five children, four of whom (two girls and two boys) survived to adulthood. Their two daughters married white men. Their two sons enlisted and served in Europe during World War I, each classified as African-American. King finally revealed his true identity to Copeland in a letter he wrote to her while he lay on his deathbed in Arizona.

Ada Copeland King outlived her husband by 63 years and survived to hear the “I Have a Dream” speech delivered by Martin Luther King.

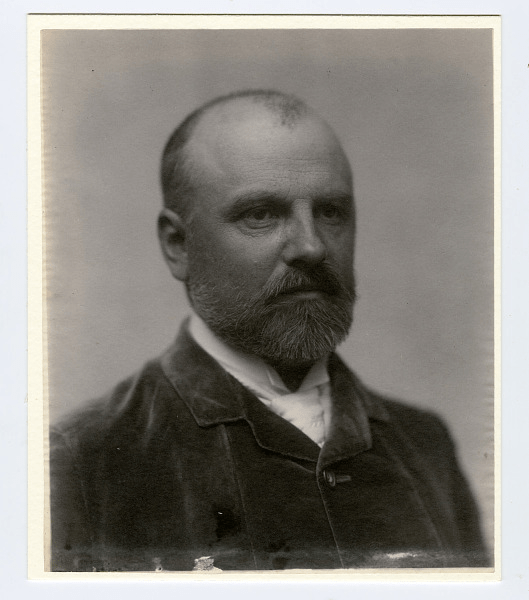

King’s Death and Legacy

King spent many of his last months clandestined and alone in a Bloomingdale Asylum in Brooklyn, NY, suffering from a serious mental breakdown. He eventually mustered the strength to move to Phoenix, Arizona, where he died on December 24, 1901, of tuberculosis. At his death, John Hay stated that he had simultaneously immense respect and heartfelt pity for the “potential” of his deceased friend, calling King: “the best and brightest man of his generation, with talents immeasurably beyond any of his contemporaries . . . with everything in his favor but blind luck, hounded by disaster from his cradle.” [3]

Several mountains have been named in honor of King, including King’s Peak in Utah, Mount Clarence King in California (John Muir Wilderness) and King Peak in Antarctica. The US Geological Survey Headquarters Library in Reston, Virginia, is also known as the Clarence King Library.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

References:

[1] The vast majority of the research of Clarence King was confined to Wikipedia, which holds a treasure trove of details that I have glossed over in this Powell’s Pals post. The more complete work, as well as invaluable primary sources, can be found in the listing: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clarence_King

[2] According to Google AI, an “undine” is a water nymph, or elemental spirit of water, originating from European folklore and first described by the alchemist Paracelsus. The term comes from the Latin word unda, meaning “wave.” Undines are often depicted as female water spirits, such as naiads or mermaids, who gain a soul by marrying a human, but risk death or a return to their watery form if the human is unfaithful. Thus, the word was sometimes used to describe crew teams, who believed their rowing action was able to create mythical and spiritual waves, as they glided through the water.

[3] Stegner, Wallace, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, Penguin Press, 1954, page 344.

[4] The list of King’s professional admirers is long, many of whom are highlighted in the Powell’s Pals post above. A brief summary of his colleagues includes:

- James Terry Gardiner: A lifelong friend and colleague, Gardiner studied with King at Yale and accompanied him on the wagon train to California. As King’s second-in-command during the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, Gardiner was instrumental to the survey’s success and became the primary caretaker of King’s secret family after his death.

- William Henry Brewer: A botanist and lead assistant on the California Geological Survey, Brewer’s detailed accounts of his expeditions influenced King to travel west.

- Josiah Whitney: The head of the California Geological Survey, Whitney took King on as a volunteer assistant. Though they had a sometimes-strained relationship, Whitney recognized King’s competency as a geologist.

- Arnold Hague and Samuel F. Emmons: Fellow geologists who worked on the Fortieth Parallel Survey. Emmons published a memorial to King after his death.

- J. D. Hague: Wrote the mining industry volume for the Fortieth Parallel Survey.

- John Wesley Powell: King preceded Powell as the head of the United States Geological Survey, a position King established in 1879. Powell is best known for his surveys of regions beyond the 100th Meridian in North America, including the Colorado River basin.

- Charles Walcott: One of King’s hires at the USGS, Walcott eventually took over as director of the federal agency after Powell, and restored King’s original vision for the organization.

The list of personal admirers is equally impressive, which helped immensely when he was seeking funding for his surveys in the western states. They included:

- Henry Adams: A prominent historian and author, Adams was one of King’s closest friends and a member of the elite social group known as the “Five of Hearts.” Adams admired King greatly and was devastated to learn about his secret life and marriage to an African American woman, Ada Copeland, after King’s death.

- John Hay: Statesman and diplomat who served as Abraham Lincoln’s private secretary and later as Secretary of State. Hay was another close friend and a member of the “Five of Hearts.” He regularly provided King with financial assistance to support King’s family and costly lifestyle after he left the USGS as director.

- Clover Adams and Clara Hay: The wives of Henry Adams and John Hay, they completed the “Five of Hearts” social circle.

- Frederick Law Olmsted: The renowned landscape architect, Olmsted was among King’s intimate friends.

Other professional and social acquaintances included:

- Timothy O’Sullivan and Gilbert Munger: A photographer and a landscape artist, respectively, who worked with King on the Fortieth Parallel Survey.

- Bret Harte: The famous novelist and poet, Harte was one of King’s friends in the New York literary circle.

- John La Farge: An accomplished painter, LaFarge was part of King’s high-society circle.

[5] See Martha Sandweiss’ book, Passing Strange: A Gilded Age Tale of Love and Deception Across the Color Line, published by The Penguin Press, 2009. Sandweiss is a Yale graduate, a prolific writer, and a professor of history at Princeton University in New Jersey.

[6] Clarence King was one of the men with whom John Wesley Powell found some of his strongest kinship. The exploration of the relationship is outlined and discussed in another Powell’s Pals post on King and eight other scientists and explorers from the Powell era.