Witness Post: Esther Peterson and the Gender Pay Gap

Over the years as a high school teacher and college professor, I have asked women in my classes to pick up the idea of “equal pay for equal work.” I asked young men if their mothers deserved the same pay as their parent’s male counterparts. Beyond their resounding, “Yes!” I encouraged them to search for answers to the continuing gap with the Uncontrolled statistics. In 2025, for example, there was an estimated 17% pay gap between men and women. And, when the statistics expand to women of color, the situation was worse: Latina women earned 58 cents on the dollar and Black women earned 65 cents on the dollar. Younger workers had smaller pay gaps, earning 95 cents on the dollar compared with men their own age. But why is there a pay gap at all? And what can we do about the disparity?

The pay gap has been debated for decades and goes back to the late 1940s, when women helped in the “War effort” and joined the work-force with grit and skills. Rosie the Riveter was real.

Why Not Equal Pay? Factors influencing the pay gap

Although it makes no sense to the students of today, there were wide-spread gaps between what a man was paid and what a woman was paid in the 1950s and 1960s. And over the years those chasms have not shrunk by much. The most common excuses are said to be systemic.

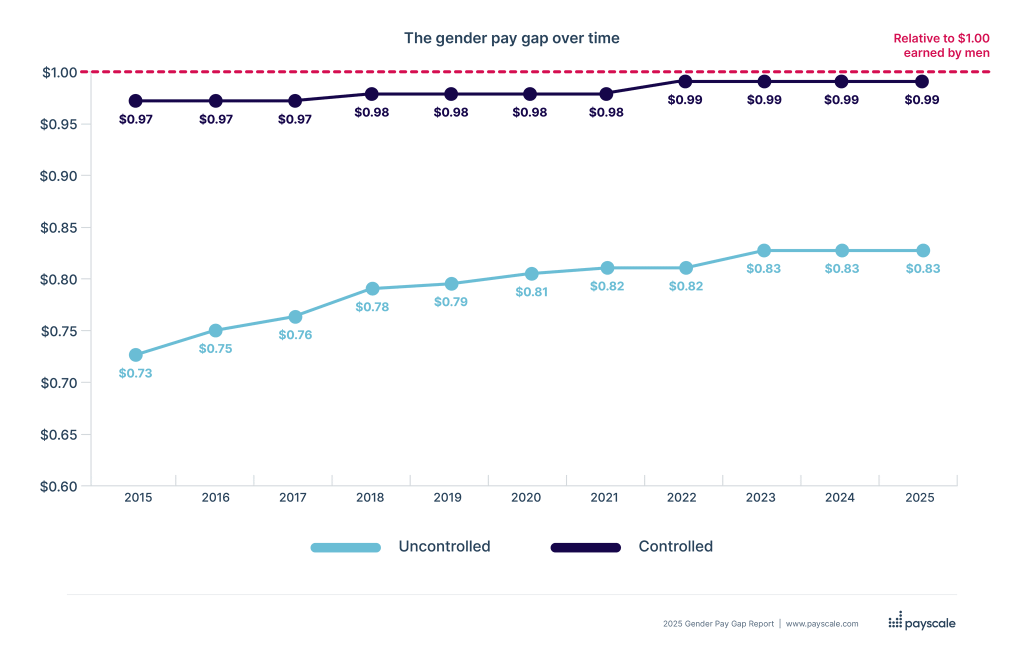

- Stagnant progress: Reports indicate that progress in closing the pay gap has been stagnant, with the uncontrolled gap remaining largely unchanged from the previous year.

- Uncontrolled vs. controlled gap: The 83-cent figure is the “uncontrolled” or “unadjusted” pay gap, which compares the median salaries of all men and women. The “controlled” gap, which accounts for factors like job, experience, and education, is much smaller, with some reports placing it at about 99 cents to the dollar.

- Systemic inequities: The wider pay gaps for women of color point to systemic inequities that contribute to the pay disparity.

For the first time since data has been available, going back to the 1960s, the gender pay gap in 2024 surprisingly widened for a second year in a row.

The average woman who worked full-time year-round in 2024 was paid just 81 cents for every $1 paid to a man; that’s down from 83 cents in 2023 and 84 cents in 2022, according to the latest data from the Census Bureau.

The pay gap grew in 2024 as men’s salaries increased while women’s stayed the same. The median income for men working full-time was $71,090 in 2024, a 3.7% bump from the year prior. Women earned $57,520, little changed from 2023, according to the Census Bureau.

Compared to what women in America experienced in the 1950s and 1960s we are in good shape, right? Let’s take a look:

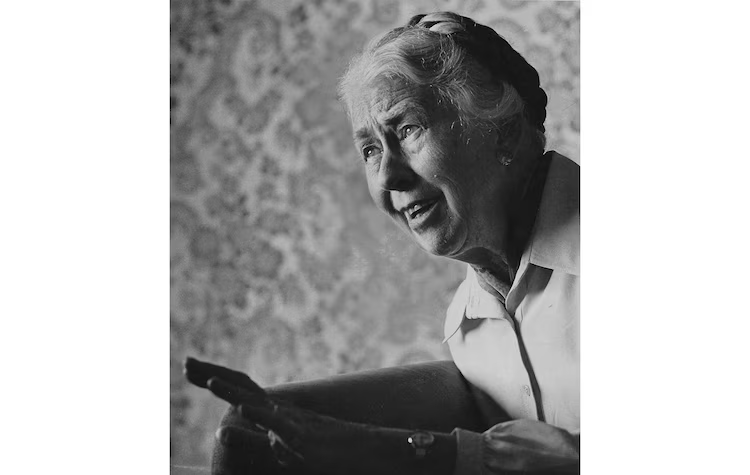

And Along Comes Esther & Equal Pay Act

Today, we have too few among us with long enough memories to hark back to the days and impact of women entering the workplace and looking for equal pay. Then along came Esther Peterson. She had a great deal of influence on the thinking of women, like my mother, Eleanor Evans Hooper. Esther Eggertsen Peterson proved to be the singular powerhouse behind the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Peterson helped raise the wages of working women, ensuring that, in at least some cases, they received the same compensation as men for the same work.[1]

Who Was Esther Peterson?

The daughter of Danish immigrants, Esther Eggertsen grew up in a family who were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Provo, Utah. She graduated from Brigham Young University in 1927 with a degree in physical education. She went on to earn a master’s from Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1930. She held several teaching positions in the 1930s, including one at the innovative Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry, which brought milliners, telephone operators and garment workers onto the Philadelphia college campus.

She moved to New York City where she married Oliver Peterson. In 1932, the two moved to Boston, where she taught at The Winsor School and volunteered at the YWCA.

Peterson’s Career

In 1938, Esther Peterson became a paid organizer for the American Federation of Teachers and traveled around New England. In 1944, Peterson became the first lobbyist for the National Labor Relations Board in Washington, D.C. In 1948, the State Department offered Peterson’s husband, Oliver, a position as a diplomat in Sweden and the family moved to Stockholm for the next nine years. They returned to Washington, D.C., in 1957. Peterson was soon to join the Industrial Union Department of the AFL–CIO, becoming its first woman lobbyist.

She later served as Assistant Secretary of Labor and Director of the United States Women’s Bureau under fellow Bostonian President John F. Kennedy. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson named Peterson to the newly created post of Special Assistant for Consumer Affairs. Extending her influence in Washington, Peterson served as President Jimmy Carter’s Director of the Office of Consumer Affairs.

Peterson was also Vice President for Consumer Affairs at Giant Food Corporation, where she led an initiative to introduce the first nutrition labels in 1971. Always working for “the people,” she served as president of the National Consumers League for many years.

Esther Peterson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1981. She was elected to the Common Cause National Governing Board in 1982. In 1990, the American Council on Consumer Interests created the Esther Peterson Consumer Policy Forum lectureship, which is presented annually at the council’s conference. She was named a delegate of the United Nations as a UNESCO representative in 1993. In that same year, Peterson was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

A year after the Equal Pay Act, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act passed, banning sex-based discrimination in hiring, firing and promotion. Together, these two pieces of legislation made illegal many forms of sex discrimination that were not only commonly accepted in the U.S., but also in some cases written into the legal code. Various state laws at the time mandated different minimum wages for women, and union contracts outlined separate pay schedules for the same job depending on sex.

While the Chamber of Commerce and other business groups fiercely opposed the bill, its supporters felt raising pay stimulated economic growth and eliminated unfair competition, ultimately benefiting men as well as women, says Rutgers University history and labor-studies professor emerita Dorothy Sue Cobble, author of “For the Many: American Feminists and the Global Fight for Democratic Equality.”

In her role as head of the Women’s Bureau in the Labor Department during the Kennedy administration, Peterson established the President’s Commission on the Status of Women to study the challenges working women faced and make recommendations to address them.

The commission’s report, which came out a few months after the passage of the Equal Pay Act, highlighted the concentration of women in lower-wage work, the toll of domestic labor inside the home and the double discrimination that minority women dealt with. It advocated for universal child care and paid leave for medical and parental needs—issues still debated today.

The report’s insights sparked a national debate over the value of women in the workforce and reinvigorated the feminist movement as different groups used it to advocate for change. Peterson, meanwhile, established the first on-site daycare center at a federal government agency, to help support her fellow employees, who were raising families.

USA 250, Celebrating 250 Years of Independence

“The Story of the World’s Greatest Economy” is a yearlong WSJ series examining America’s first 250 years. Read more about it from Editor in Chief Emma Tucker.

[1] Esther Peterson, one of the important people in our first 250 years.