Wrestling: Yale, a long tradition, now dead

This Witness Post honors the history of Yale wrestling, thus it is a tribute to the University and the sport. While many assistants and trainers, and drop-in exercise enthusiasts added to the quality of wrestling in the room, no one can argue that there was a powerful chemistry between wrestlers and their coaches: between Coach Izzy Winters and the Dole brothers, between Coach Eddie O’Donnell and Larry Pickett and Andy Fitch, between Coach Bert Waterman and the McEwan brothers and Jim Bennett. Each of these characters is worthy of the extra time and editorializing for their accomplishments in the now extinguished spotlight.

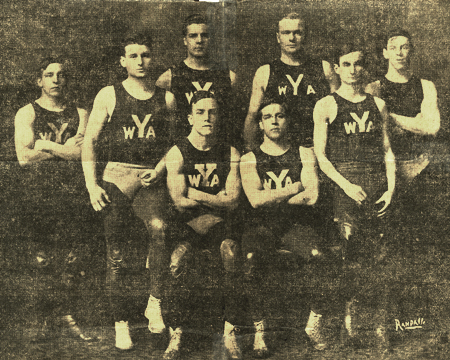

Yale Wrestling Legacy Started pre-1900

Yale officially started an intercollegiate wrestling program in March, 1903, with a match versus Columbia. That first contest was held in Morningside Heights, New York City on the Columbia campus. The rules of wrestling at the time were different than today, with a “two-fall” requirement to earn a win. There were four official matches that spring day: Yale won two of those contests. Columbia also won two, with the second by forfeit. (Yale did not have a heavyweight contender). The two wins a piece rendered the team score as tied. In the rematch, held in New Haven one week later, “Yale won.” Officially the Eli’s won two bouts, Columbia forfeited one, and one bout ended in a draw — giving the Yale Bulldogs a 2.5 to 1.5 point edge over the Columbia Lions.

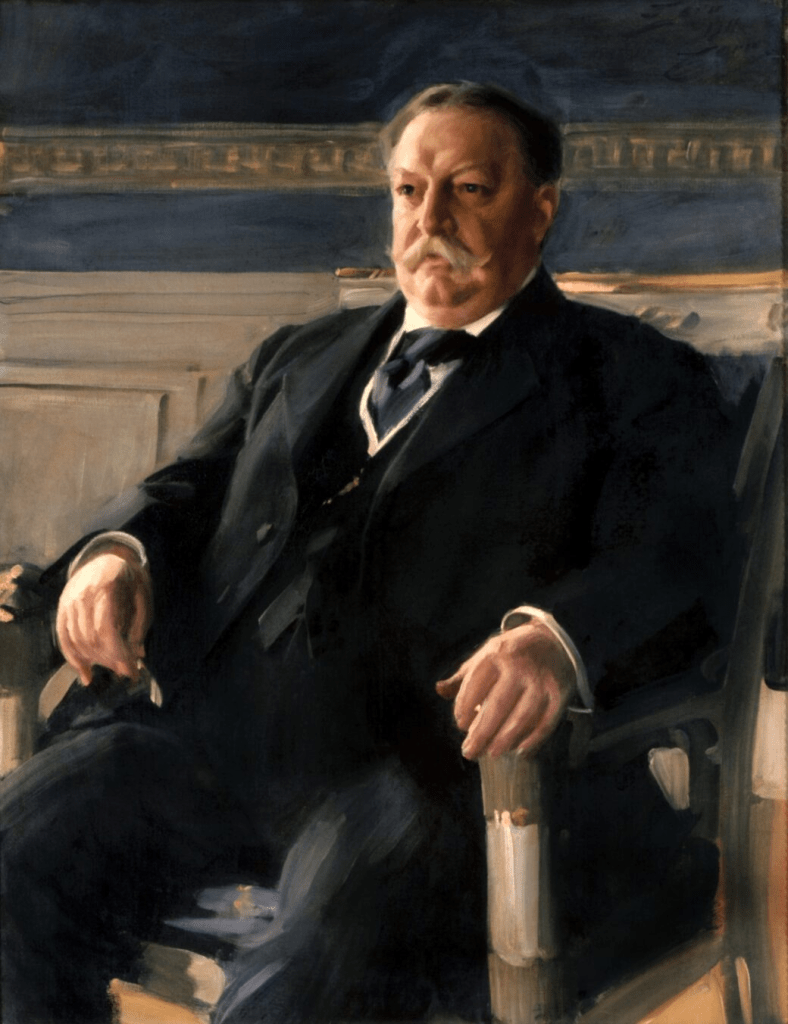

Yale claims to have had a long history of competitive wrestling, even before these intercollege matches. In 1876, William Howard Taft (Yale class of 1878 and 27th U.S. President) declared to have come from a long line of wrestlers. According to the Yale Daily News, Taft said he was a seventh generation college wrestler. He competed in the intramural leagues at Yale College and claimed he was Yale’s first intramural heavyweight wrestling champion.

Yale workmen constructed a special chair in Woolsey Hall to accommodate President Taft’s extra-wide girth, when he arrived on campus for concerts. Biographers of Taft say that he was known for his super-sized bathtub in the White House. They also credit Yale’s “Professor” Izzy Winters (the wrestling coach) with substantially reducing President Taft’s weight, through a combination of strict diet and regulated exercise.

The coach of that first Yale intercollegiate team was Isadore L. Winters, “a young man from the neighborhood.” He was selected by the athletic department for his wrestling prowess as the head coach of their new collegiate team.

Yale Coach Izzy Winters

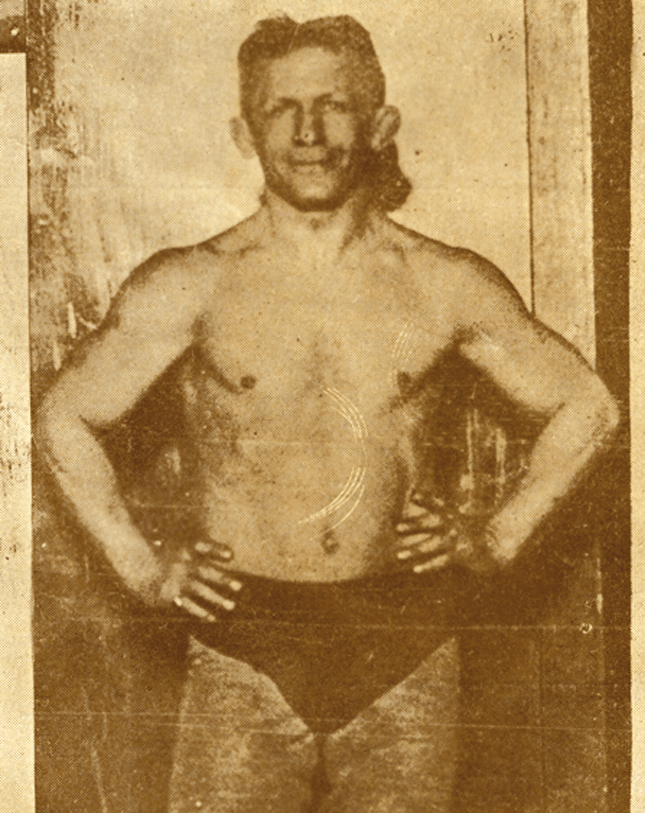

Isadore Louis “Izzy” Winters was a character in his own right. Born in 1886, Winters was a Jewish immigrant from Austria who grew up in New Haven, Connecticut. He left school at the age of 14 and two years later (1902) he achieved national prominence by winning the US lightweight wrestling championships. He then toured America with a burlesque troupe of exhibition wrestlers, including the pioneering female champion, Cora Livingston.

Winters’ wrestling coaching career started at Yale in 1903, after his American tour. He was 17 years old! Although he was tapped as coach at Yale, Winters continued to wrestle professionally, competing in over 600 bouts in all. Winters was an exercise professional and a coach of champions. He is credited with coaching 19 championship teams of Yale grapplers. (One of those teams was captained by his nephew, Hyram Winters ’25S.) Izzy Winters believed that getting a team in peak physical condition was even more important than teaching the fundamentals of wrestling. “When I’m judging a coach,” he said, “I look at the bench to see how many of his players are crippled. That shows whether he’s doing a good job” or not.[1]

The Dole Twins

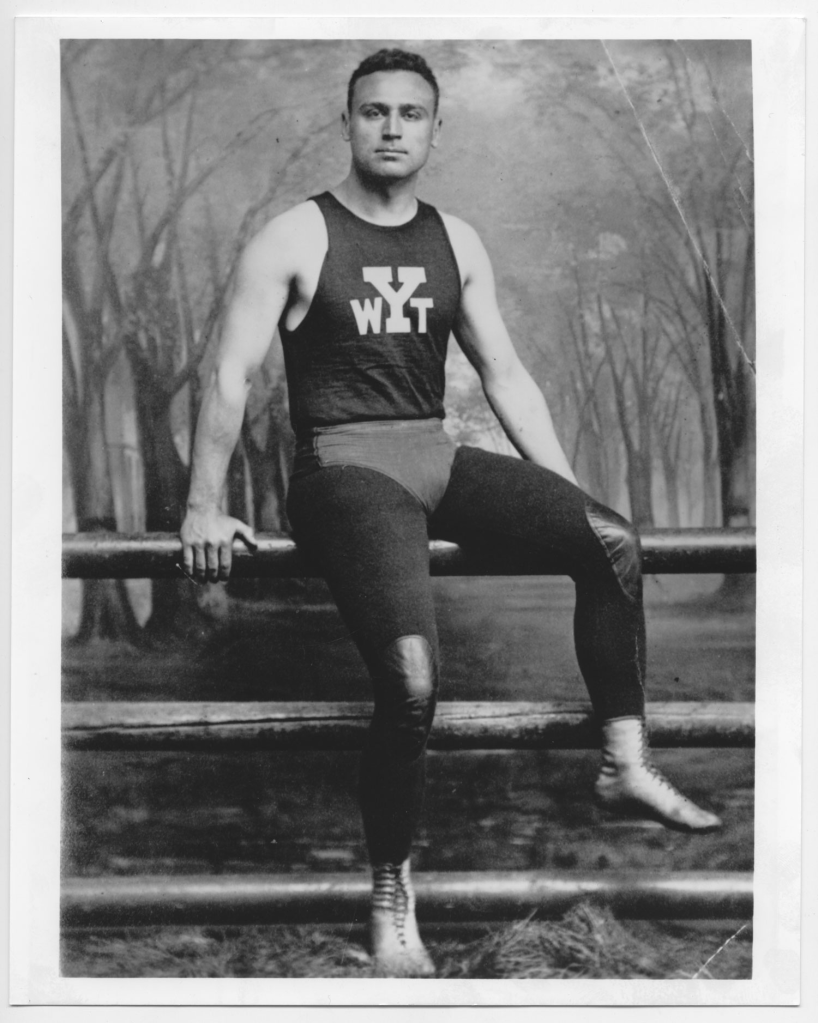

In the early years of collegiate wrestling, before the creation of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), Yale competed head-to-head with the best college programs in the country. From 1903-1906, George and Louis Dole were two phenomenal Yale wrestlers. Originally from Ypsilanti, Michigan, the Dole family moved to Maine, and the boys attended Bath High School and Milton Academy in Massachusetts. The Dole brothers were identical in appearance and weight. In matches, they alternated who would wrestle the lighter weight class, a designation awarded to the twin who won the wrestle-off at practice that week. They were singular forces, each winning multiple collegiate wrestling titles. Thanks to the Dole twins, Alfred Gilbert, another successful lightweight, and Coach Izzy Winters, Yale become the annual Eastern league champs from 1905-1909 and a powerhouse wrestling program for several years.

George Dole (Yale ’06), had a collegiate record of 100 wins and 1 loss. In those college years he won four national titles. His brother, Louis Dole (Yale ’06), won three national titles. George was the first collegiate wrestler to become a 4-time champion. George Dole and Izzy Winters both coached the Yale squad for the next few years. In 1908 George went to the Olympic trials, and he earned a position on the US team. He sailed with the team to London, England and went on to win a gold medal in his weight class in the summer Olympics.

The US and other country Olympians continued with some exhibition matches in Europe before navigating back to their respective countries. When George Dole returned from Europe, he was an instructor at Milton Academy in Massachusetts, his alma mater. One of his many duties was to be the head wrestling coach. After his wrestling and coaching careers ended, Dole joined the U.S. Navy in 1917. He commanded a submarine-chaser (USS C-354) during the war and was awarded the Navy Cross for “exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service … engaged in the important and hazardous work … clearing the North Sea of mines.” He died in 1928.

Wrestling in the Easterns League

Known as the EIWAs, the Easterns league is the oldest wrestling conference in the NCAAs. The league in its first year (1905) consisted of four Ivy League colleges: Columbia, Princeton, Penn and Yale. As years went by the league added state colleges and independent schools in New England and the Mid-Atlantic region. The EIWAs by 1910 consisted of Columbia, Princeton, Cornell, Pennsyvania, Lehigh, Penn State and Yale. (Yale withdrew from the league competitions in 1910, in a dispute over the use of graduate students in matches. And although they lost a step, Yale emerged victors again when they re-entered the Eastern intercollegiate competitions in 1916.)

The Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and Army, in West Point, New York, which competed against teams enrolled in the EIWAs, were not officially added to the league until after World War II.

Yale & Wrestling during and after WW I

During World War I, Izzy Winters stepped aside from coaching and served in the Navy at the Pelham Bay Training Station. Working for nominal pay, he taught all sailors and marines the martial art of jujitsu. In 1921 he joined Yale president James Rowland Angell’s program for Yale’s well-known athletes and coaches to train community leaders. According to the New York Times, the goal of the program was to make New Haven “a great centre of athletics and recreational work for all classes.” The faculty of New Haven’s “School of Coaching” included Izzy Winters, football coaching legend Walter Camp ’80, Charles Taft ’18 (son of President Taft), and boxing coach Mose King.

In 1926 Coach Winters resigned from Yale to turn his full attention to physical training. His principal interest was his New Life Health Farm and the health institutes.

Through the 1950s Winters was featured in many newspaper and magazine photo spreads, proudly displaying his muscular torso and weightlifting strength. His health and exercise “institutes” in New York and in New Haven (one in West Haven, one in the Taft Hotel) predated even Jack LaLanne’s. His celebrity clients included the professional boxers Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey, as well as entertainers Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Lanny Ross Y’28 and Rudy Vallee Y’27. He often spoke on television and radio on the importance of maintaining fitness throughout life, asking rhetorically, “Does it do any good to be the richest man in the cemetery?” Winters, who never married, died in 1979, at the age of 93.

Yale Wrestling Coaches of Note

Although there was a long dry spell in Yale wrestling prowess from the Dole brothers and Coach Winters, at the turn of the century, to the 1940s, there were some other notable coaches and champions along the way.

One of the early Yale wrestlers and notable Winters proteges was Walter O’Connell. He had been a student coach at Yale after his collegiate days, and Cornell wanted to hire a winner. Recruited to be the head coach at Cornell in Ithaca, New York, O’Connell proved a winner. He stayed at Cornell for forty years (1908 to 1947). And he earned his stripes by coaching 12 regional EIWA championship crowns and many individual stars for Big Red over that time.

Dr. Raymond Clapp, a Yale wrestler and pole-vault world record holder, became a prominent figure in the sport of wrestling in the mid-west. Clapp coached wrestling teams at the University of Nebraska for 15 years (1911 to 1926) with good success. And when he retired from coaching, he become the head of the newly formed NCAA Wrestling Rules Committee in 1927, setting the standards for collegiate wrestling (a.k.a. folkstyle wrestling) for the next century.

NCAA and Conference Competition Begins

From years before intercollegiate competitions, all matches were declared to be intramural. The first intercollege match was between Yale and Columbia (1903). The next step was in the creation of the regional leagues, or conferences, such as the Easterns (EIWA founded in 1905). Other conferences were created over the decades, including the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), the Ivy League, the Southern Conference (SoCon), the Big 12, the Big Ten, the Mid-Amerian Conference (MAC), and the Pacific 12 Conference (PAC12).

It was not until 1928 that the first official National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was created. That year the wrestling finals took place at Iowa State University, in Ames, Iowa. The wrestlers were all competing purely as individuals in seven weight classes, thus there were no official college team place winners. The first official team championships were awarded six years later, in 1934. That year Oklahoma A&M was declared the first team winner of the National Championships.

The different NCAA divisions (DI, DII, and DIII) were created over time to give smaller, and non-scholarship colleges the opportunity to participate. While some sub-divisions have come and gone (NAIA, NCWA), the NCAA has stood the test of time in the US since its founding.

The weather forecast for the NCAA in the years ahead, with NIL contracts, the athlete portals and paid student/athletes, appears “cloudy with the chance of heavy weather” for all non revenue-positive teams and sports. We shall see.

From Winters/Dole to O’Donnell/Pickett

While Cornell had Walter O’Connell as its longtime coach, Yale had another Irish family, the O’Donnells, involved in coaching its wrestling teams. Edward T. “Eddie” O’Donnell, Class of 1930, coached Yale wrestling for at least the 1930s through to the late 1940s. Then, his much younger brother, John E. O’Donnell Jr., Class of 1948, coached Yale teams into the 1960s. Together, the O’Donnell brothers shaped Yale wrestling for multiple decades, establishing what became known as O’Donnell-style wrestling.

The first Yale athletic trophy for wrestling came along in 1930. The Wade Cup was given by William H. Wade in memory of his father, Frank Edward Wade (Yale 1896). William Wade (Yale 1930), a conspicuous figure in wrestling at Yale, was an enthusiastic follower of the sport, as was his father. The Cup was given annually to the varsity wrestler showing the greatest improvement. Coach Eddie O’Donnell selected the award winners during his era.

Yale also annually awarded the John O’Donnell Trophy to the best wrestler on the team in recognition of their athletic success and sportsmanship.

Larry Pickett in the uphill charge [3]

The international turmoil of WWII in the early 1940s gave urgency to the sport of wrestling at Yale and across the nation. At the time, Yale’s coach, Eddie O’Donnell, was near the end of his coaching tenure, and the team needed some juice. One breakout wrestler in that era was Larry Pickett, a heavyweight in the Unlimited weight bracket, the captain of the Yale squad. After attending Gilman School in Baltimore, Maryland, Pickett went to Yale and majored in Biology, during his war-shortened time in college.

In Pickett’s NCAA tournament appearence in 1941, Pickett defeated Thomas Davies of West Virginia by a score of 7-0 in the opening round, then he pinned Bill Bennett from Wisconsin in 2:00. In the semifinals he won by fall in 4:55, defeating Lloyd Arms from Oklahoma State. He lost in the finals to Leonard Levy of Minnesota by a score of 5-2, which earned him second place honors and All-American status.

Pickett had a talented teammate in 1941: his name is John Castles. The Pickett/Castles duo gave the Elis some much needed mojo in those WWII years. Castles competed in the 136-lb weight class. He had a long tournament: in the first round he defeated Marvin Applebaum of CCNY by a 10-3 score. The next round he beat Lindo Nangeroni of Rutgers by a 10-4 decision. After collecting a bye in the following round, he lost to Al Whitehurst of Oklahoma A&M by fall in 7:16.

Because of that loss to Whitehurst, John Castles dropped into the consolation bracket, where he defeated Frank Gleason of Penn State by a 7-5 decision. He went on to secure 4th place and All-American status for the Bulldogs. Along with Pickett’s runner-up position, the Eli’s did well that year.

After college Larry Pickett was recruited to the Boston Children’s Hospital and trained at the Brigham Hospital where he became skilled in general and pediatric surgery. He is credited with coauthoring a pull-through procedure for Hirschsprung’s disease, where an infant loses nerves and cannot move their bowels or large intestines. Pickett felt the procedure was his proudest pediatric accomplishments. Pickett worked at many teaching hospitals, including Yale-New Haven. Over his lifetime Larry earned honors from Yale including the Francis Gilman Blake Award in 1969, the highest recognition for teaching awarded by the school, and in 1972 he became the William H. Carmalt Professor of Surgery.

Despite suffering from asthma, Larry Pickett refereed wrestling at the college level in New England during his retirement, as recalled by the Yale wrestlers.

O’Donnell era nears an end and Andy Fitch on the rise

In the 1950s Yale had several All-Americans on their squad, including George Graveson (1951), and Andrew “Andy” Fitch (1959). The coach during this era was John O’Donnell, who was winding down the 3+ decade of O’Donnell coaching prowess. (Coach John O’Donnell was entered into the EIWAs Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2001.)

Andy Fitch was one Yale wrestler for the record books. An athletic prodogy out of New Rochelle, New York, Fitch attended The Hill School in Pennsylvania. The head wrestling coach at The Hill School was Frank S. Bissell (coach from 1947–1973). Under Bissell’s leadership in the 1950s, Hill became one of the most dominant prep school wrestling programs in the country. Fitch flourished under Coach Bissell, winning an individual title as National Prep champion in 1955. [2] The National Preps are held annually at Lehigh in Pennsylvania and often draw national attention and scouting by college coaches.

Fitch took his wrestling success to the next level through his involvement in the freestyle practices and open tournaments held at the New York Athletic Club (NYAC). Harking back to his high school days, Fitch claimed: “The New York Athletic Club was my wrestling education. NYAC was one of the best freestyle teams in the country. I was lucky enough to hook up with a good high school coach [Coach Bissell] who taught me a lot about wrestling, and by the time I got to college at Yale, I was better than most.”

Fitch proved to be one of the few solid EIWA stalwarts during his tenure at Yale. Although he never won the EIWAs, he peaked at just the right time for him to reach the top of the podium at Nationals. He wrestled at 123 lbs., the lightest Easterns weight class at the time for all four of his years at Yale. Fitch’s natural weight was about 120, so he dropped 5 pounds to compete in the 115 lb weight class for national tournaments. In his junior year (1958) he placed 3rd at the EIWA tournament losing to the first seed, Dave Aubel of Cornell in the semi’s, and beating Jerry Weisenseel, the second seed from Army, in the consolation finals. Fitch was unseeded at the NCAAs, wrestling at 115 lbs that year. He lost a key match in the early rounds and did not place.

As a senior (1959) Fitch was voted captain of his Yale team and was undefeated in league matches, earning a ton of momentum going into the EIWA Championships (held at Cornell). Once again Fitch competed at 123 lbs. He was the runner-up (2nd place), losing another tight match versus Dave Auble of Cornell in the finals of the Easterns tournament. For the NCAAs he dropped to the lower weight class (115 lbs.) and was seeded 4th in the brackets for his weight. Then Fitch went on a pinning spree. After a bye in the first round, Fitch pinned Fred Lamb of Indiana in 3:55. And in the next round he pinned Mitsi Tamura of Oregon State in 6:58. The pins propelled him to the semifinals. In that semi’s he defeated the number 1 seed, Bob Taylor of Oklahoma State, by a 5-2 decision. And in the finals he had a tough duel. That last match was against the first seed, Dick Wilson of Toledo. At the end of regulation time, the score was tied (3-3), which sent the match into overtime. During the extended session, Fitch eked-out a narrow 5-4 decision over Wilson to earn the Nationals title at 115 lbs. Fitch became only the third Yale wrestler to reach this pinnacle in the sport. The Dole twins were the other champions. (Note that the Dole brothers competed in the pre-NCAA era of wrestling.)

Andy Fitch, in total, had an impressive collegiate career record at Yale of 36 wins and 5 losses, with 12 wins by pins.

One take-away from Fitch’s collegiate success is that someone can be superior at Nationals (NCAA tournament) even without winning their conference title. The EIWAs were often deep in talent, so winning the regional qualifier was a huge feat. Fitch peaked at the perfect moment to rise above his regional loss to Auble of Cornell and to reach the top of the podium and the national crown. (Read about the similar path to the NCAA finals by Jim Bennett later in this post.) It definitely helped that Fitch switched to a lower weight class for the finals. Dave Auble from Cornell, by the way, was a three-time EIWA winner and two-time NCAA champion at 123 lbs and he placed 4th at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964.

Fitch post-college goes International

In an article in May of 1960, the Yale Daily News had some interesting reports about Andy Fitch after graduation. The article cites that “Andrew Fitch, the former Yale Captain and National Champion, places second in the Olympic wrestling regional finals scheduled in Ames, Iowa. The top three men in each of eight weight class will report for the training camp, finals trials and team-selection in Norman, Oklahoma, in July. Fitch and Dick Wilson squared off in the 114.5 lb weight class and they were tied in points after their last match, the same as they had been at the NCAAs last year, with Fitch winning in OT. This time, however, Wilson was declared the winner. Olympic rules state that in the case of a tie, instead of having an overtime period, the winner is the lighter of the two wrestlers. Wilson petitioned for a weigh-in after the match and was six pounds lighter than Fitch. Coach John O’Donnell, Fitch’s former mentor and Yale coach, said that, despite the loss, he hoped Fitch could go all the way at the Olympics.“

In 1961 reports mentioned that Fitch wrestled for NYAC. The club was a frequent supporter of athletes who have international aspirations. Their newsletter summarized, “Fitch scored two quick pins at the second annual Eastern Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) wrestling championships. Representing NYAC, Fitch triumphed over Dave Huff of the Elizabeth (NJ) YMCA in 2:05 and then threw Leo Laiback of Freeport, Long Island, in 3:27. The Fitch victories were scored in the 125.5-pound class. Under international freestyle rules, all a wrestler had to do was to touch his opponents’ shoulders to the mat for an instant to win. In both encounters the Winged Foot NYAC performer and Yale grad made quick take-downs and worked his way to the falls.”

In 1963 Andy Fitch went on to win a gold medal for the US in flyweight freestyle wrestling at the 4th Pan American Games, held in São Paulo, Brazil. One year later (1964) he did not earn a spot on the US freestyle Olympic team; however, he did qualify for Greco-Roman competitions. He wrestled bantamweight (<57 kg, or 114.6 lbs to 125.7 lbs) at the 1964 summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. In the first round of the Greco-Roman matches Fitch lost to Fritz Stange from Germany by decision, and in the next round he defeated Nour Ullah Noor of Afghanistan by decision. In the third round match he finished in a tie versus Tsvyatko Pashkulev of Bulgaria. Under international scoring rules (a.k.a. the black mark system), Fitch’s combined loss, win-by-decision and tie eliminated him from medal contention, due to the 6 black marks he had accumulated.

Fitch has always maintained his enthusiasm for the sport of wrestling. He even made a run, in the early 1970s, at creating a league for professional wrestling. He said, “I wanted to help start a professional league. We had two events which were rather successful as athletic events, but rather ruinous financially.” Full of gusto for many years thereafter, Fitch joined Yale friends and and classmates travelling the globe. He even ran with the bulls through the steets of Pamplona, Spain.

Professionally, Andy Fitch managed the Fitch-Febvrel Gallery in New York City for many years, before going private in 2005 in Croton-on-Hudson, NY. Fitch-Febvrel specialized in fine print-making. In 2013 Andy Fitch was inducted into the Westchester Sports Hall of Fame. Andy Fitch and his wife, Dominique, have lived for many years in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, a village in Westchester County along the Hudson River. In local reporting from 2025, the Fitches are described as residents who are active in the community and enjoying life there with their toy poodles.

The Waterman/Bennett Era

In the 1960s, after the Fitch and O’Donnell era, Yale was only able to claim three NCAA All-American wrestlers, when Henry “Red” Campbell was coaching: Bob Hannah (1964), Ken Haltenhoff (1965), and Tom McEwan (1968). That is when Coach Waterman came on the scene.

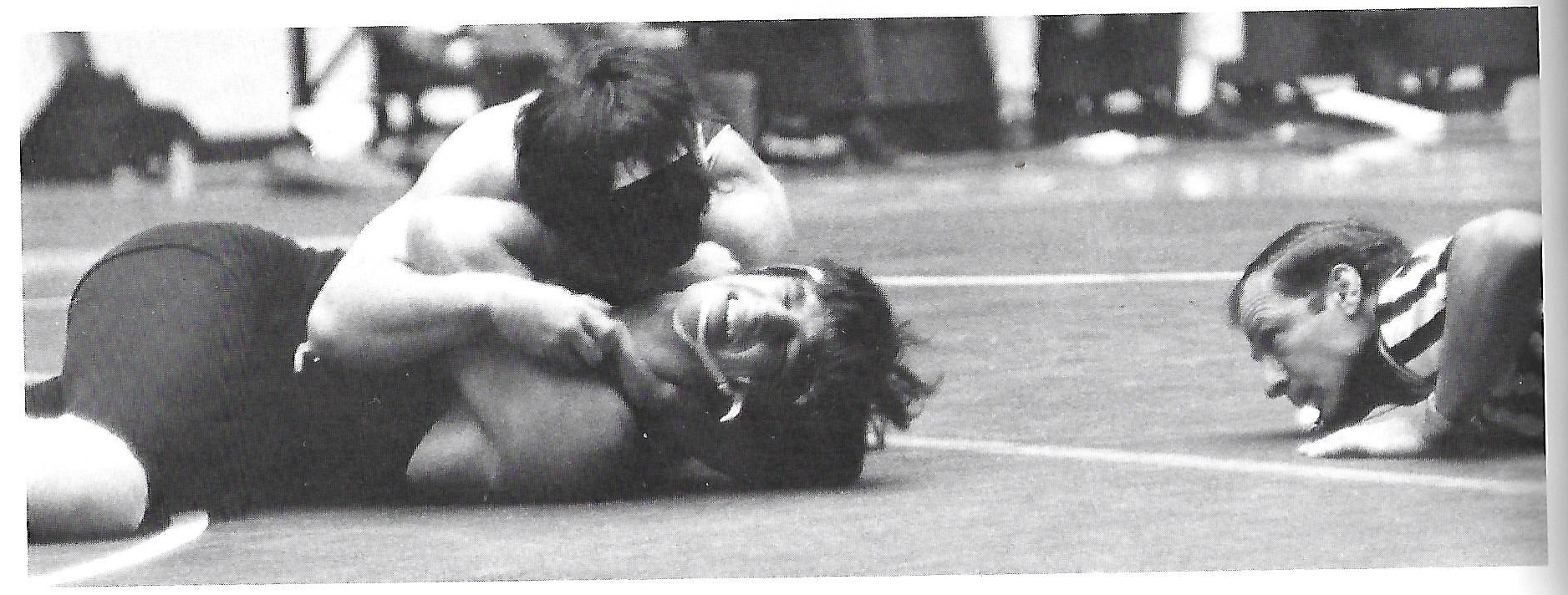

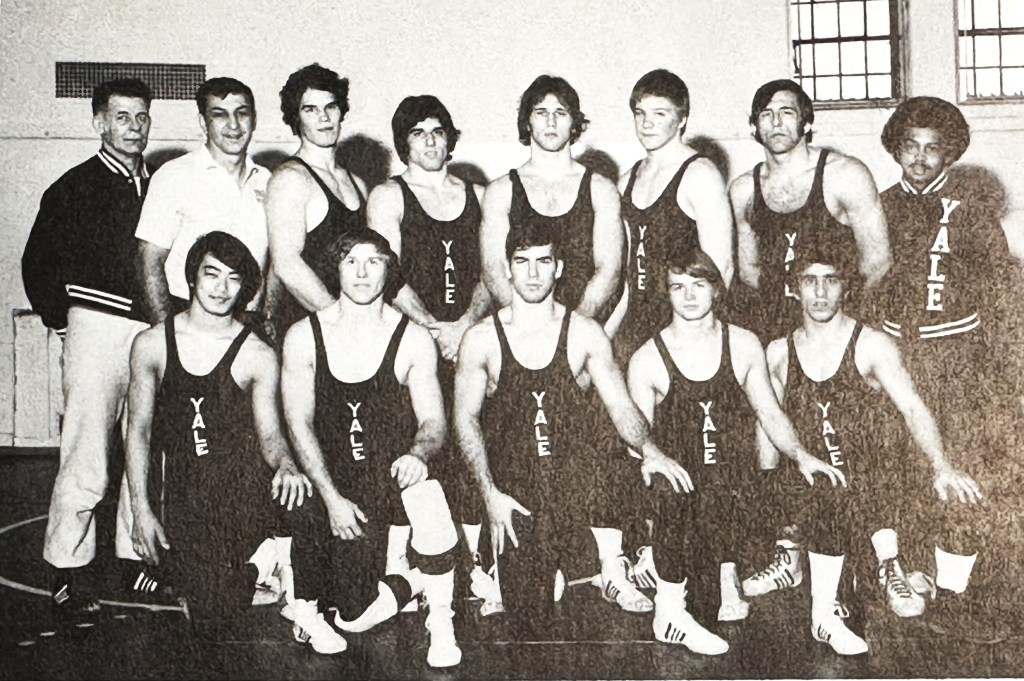

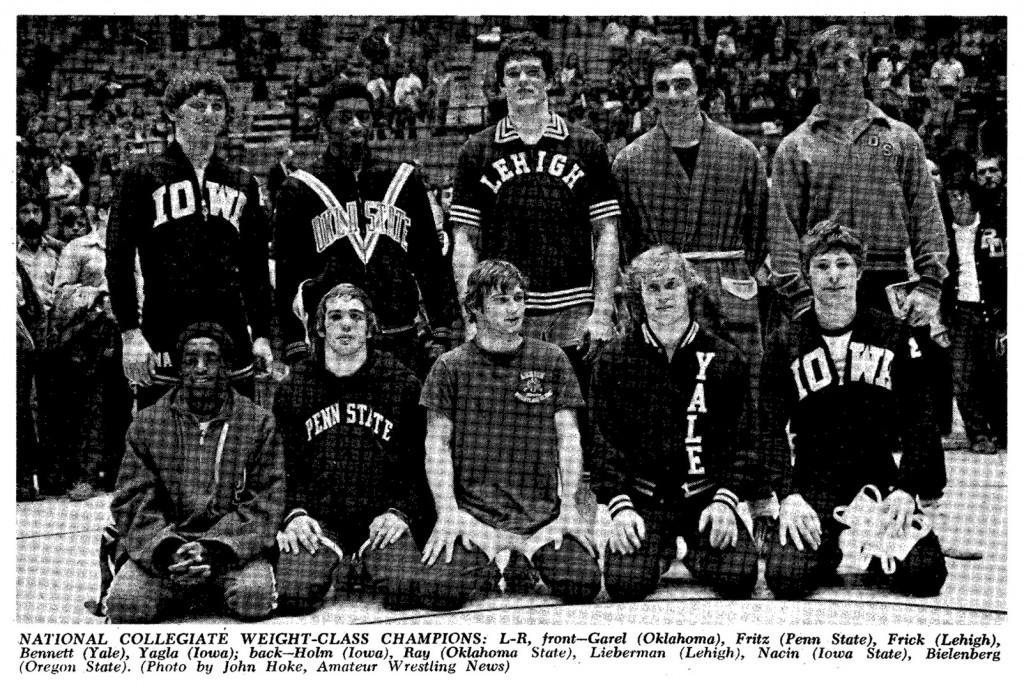

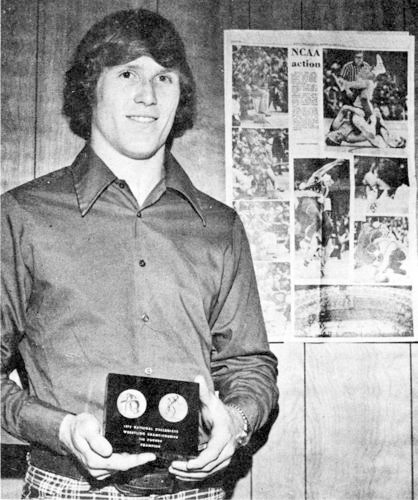

In the 1970s and 1980s Yale wrestlers, under coach Bert Waterman, hit their pinnacle. The Eli’s had All-Americans Tim Karpov (1974), Neal Brendel (1976), Jim Bennett (1975, 1976), and Colin Grissom (1982). Grissom, by the way, earned a degree in molecular bio-physics and bio-chemistry. As the fans at the Nationals exclaimed, “Only at YALE, would someone be an MB&B genius and not a phys ed major!”

Jim Bennett was a double major in Economics and Russian Studies, so not an academic slouch. He stood atop the podium in the NCAA’s Div. I finals in 1975.

Waterman Enters the Scene

Born in Nebraska in 1925 and raised near Omaha, Bert Waterman was the consummate wrestler. His family moved to Michigan when he was in high school. In his senior year he was a Michigan state champion, crowned in 1944. Immediately after high school Waterman was drafted and he served in the Navy in the Pacific Theatre for two years. He was honorably discharged in 1946 and attended college at Michigan State in Lansing, on the G.I. Bill.

After graduating from Michigan State in 1950, Waterman became the head wrestling coach at Ipsilanti High School in Michigan. He led his team to their first of four championships during a 10-year span starting in 1956. The Ypsi Braves during Waterman’s tenure posted a remarkable 192-35-4 record in 16 seasons. With the start of the 1967-1968 school year, Waterman was selected as the new wrestling coach at Yale. That season he embarked on a 24-year career as head coach at Yale University.

Tom McEwan, as Captain of the Yale wrestling team in 1968, said that he had given the newly appointed Coach Waterman a tough time that first year. Tom had really liked the style of the former Yale Coach, Henry “Red” Campbell, who was at the helm for five-years, coaching after John O’Donnell and before Bert Waterman. Coach Campbell resigned that year and Waterman had succeeded him. McEwan later acknowledged, “I was not happy to see Coach Red Campbell replaced, so I never really gave Waterman a chance. I quit when Campbell left.” Fortunately Tom McEwan and Coach Waterman mended fences, as they were both quality people and hard charging athletes who demand the most from themselves and those around them.

Yale Wrestling Stories from the 1970s

In those years of NCAA Division I competition, Yale teams placed twice among the top 20 programs in the country. In the years of 1970-1976, Yale under Waterman produced one NCAA champion — Jim Bennett (142 lbs) — and several other notable wrestlers, who were strong contributors to the program. As Bert Waterman hit his coaching stride the results from his wrestlers were astonishing: Alan Gaby, Chris Legg, Frank Kreiji, Jeff Spendelow, Tim Karpov, Marty Schwartz and Neal Brendel, along with Jim Bennett, were all scoring machines.

The Captain of the Yale Wrestling Team in 1972-1973 was heavyweight, Tim Karpov, an All-American with a ferocious temper. With team points coming in tournaments from many weight classes (Bill Gamper, Brian Robb, Mike Poliakoff, Ken Stewart and Kent Weichmann), Yale was perennially considered an Ivy League contender, an Eastern’s (EIWA) dark horse, and an NCAA surprise.

McEwan Brothers & Brendel

In the fall of 1972, when the class of 1976 arrived in the wrestling room, Coach Bert Waterman told the team that there was a good 167 pounder, Jamie McEwan, who had taken the previous year off to qualify for the Olympics in another sport – whitewater canoeing. Coach said that Jamie’s brother, Tom, was also a canoe star and he had been the captain of Waterman’s first Yale wrestling team. Sounds like the Dole twins.

The McEwan boys grew up in Olney, Maryland, and spent many waking hours paddling with the family on the Potomac River. Their father set up a canoe course near a small set of rapids on the Maryland/Virginia state line. Jamie and Tom were both multi-sport (wrestling and canoeing) scholar athletes. They attended Landon School in Bethesda, Maryland. Both McEwan boys graduated at the top of their high school classes and attended at Yale.

Jamie won the Bronze medal in white water canoeing at the 1972 summer Olympics in Munich, and returned to New Haven to continue his studies. He was the captain of the wrestling team during the 1974-1975 season.

The brutalist on the team was Neal Brendel (190 lbs), who was a Pennsylvania Catholic league champion from Serra Catholic in McKeesport, PA. He often battered his wrestling opponents and practice partners, even during warm-up sessions and take-down drills. Neal had one speed: ALL OUT! Screams from Neal’s side of the practice room, were ignored by Coach Waterman, especially when Brendel and Karpov squared off.

Wrestling Neal Brendel was always a challenge for Kent Weichmann, Ken Stewart, Tim Karpov, Jim Simpson, Jack Moses, Joe Cooper, Sam Teeple, Frank Jackson, and the rest of the heavier team members. Everyone knew they would finish practice with a hyper-extended elbow, a broken nose, or flesh wounds of some kind to show for the effort. Partnering for drills with McEwan, was a fulfilling experience, all things considered. He could crank it down a gear and go half-speed which helped team mates to learn the move Waterman was drilling. Neal never mastered that lower gear.

In the winter of 1974 Yale formed a Club team to compete in the Montgomery County Community College, Maryland wrestling tournament. The team consisted of Jim Bennett, Jamie McEwan, Henry Hooper, Craig Davis, Neal Brendel and Tom McEwan. During one of Bennett’s early round matches, Coach Waterman got so angry at the referee that he stood up, lifted his seat and threw it across the gym. The metal chair went clattering across the wooden floor, as Coach berated the official’s calls. The referee soon ejected Coach from the gymnasium. Waterman kept yelling at and heckling the ref from the exit door to the locker room. They finally called security, who escorted Waterman from the premises. The team esteemed Waterman for his passion and his fire. He was a formidable man with a very loud baritone voice which resonated in gyms, even from the exit doors. Bennett stated, “I have never had a coach who cared that much about me before.”

Bennett / Waterman’s Best

Jim Bennett was a multi-sport force in his own right. A Pennsylvania High School (PIAA) wrestling champion from Corry Area High School in Erie, PA, Jim was also a track and field star. He set a high school record in the pole vault at the time and was a two time pole vault state champion. “I was a good wrestler those days because I was able to work out with the Carr brothers, who were all excellent matmen in the Erie area during my time.” Indeed the Carr brothers were even more prolific than the Dole twins! Brothers Jimmy Carr, Fletcher Carr, Joe Carr and Nate Carr were all celebrated for the Carr family’s multiple Pennsylvania high school champions, NCAA All-Americans, Olympic medalists, and world champions. Wrestling with the best improves your skills dramatically.

Bennett described that the “potholes” along the NCAA highway his junior year included a number of well-known grapplers. Bennett had beaten Navy’s Dan Muthler, another PIAA champ and the defending NCAA champion at 142 lbs. in the dual meet, so he had confidence and momentum. However, Bennett, who was the 1st seed, had placed second in the EIWAs, losing (6-4) to Lehigh’s Pat Sculley. That loss left Bennett unseeded going in the NCAAs. The tournament was held at Princeton that year, but there was no Ivy League glide-path to the podium. All-in-all it was a rough road to the championship round.

At the tournament Bennett defeated John Martellucci (Brockport State), 6-1 in the preliminaries. Then he met Larry Reed (No. Colorado State) in the next round. Reed had a season record of 32-2, before matching up with Bennett. During all of his time in the neutral position, Reed wrestled on his knees, “like a monkey; I couldn’t believe it,” commented Bennett. In the second period, the Yalie reversed Reed and put him on his back, eventually winning by a 7-4 decision.

Next up were the quarterfinal matches. Bennett faced the No. 1 seeded Steve Randall of Oklahoma State. Randall had lost just one match in two years, and that loss was in the finals of the NCAA’s the year before. Randall was heavily favored over the unseeded Bennett. With a takedown in the final 30 seconds of the first period, Bennett drew first blood. In the second period, Randall was on top. Stan Able, the Cowboy’s coach, began yelling defensive advice with increasing pitch, “Watch the granby, watch the Granby, Watch the GRANBY.” Jim earned an escape point by executing the Granby roll. Waterman commented that he was indeed watching the Granby, which Jim executed to perfection. Bennett quickly followed the escape with another takedown earning him a five point lead.

Bennett rode Randall from the top position with leg rides for all but a few seconds in the third period, before Randall escaped, getting his only point in the match. Bennett earned an extra point for riding time. In a post-match interview, Bennett mentioned his chances in the finals. “I knew I could do it after I beat him (Randall).” Buoyed by his 6-1 triumph over the top seed that Friday afternoon, Bennett added, “I’m usually a conservative, cautious wrestler. I was surprised I beat Randall so easily.“

Bennett’s quarterfinal victory over Randall set the stage for a semifinal match versus Purdue’s Alan Housner on Friday night. That evening match, a win for Bennett, was not as close as the 7-6 final score indicates. Bennett was ahead by 6 to 2 at the end of the second period. Housner tallied four markers versus Bennett in the final 45 seconds of the third period, which included a stalling point against Bennett. The Bulldog grappler had the bout locked up, plus riding time, earlier in the match.

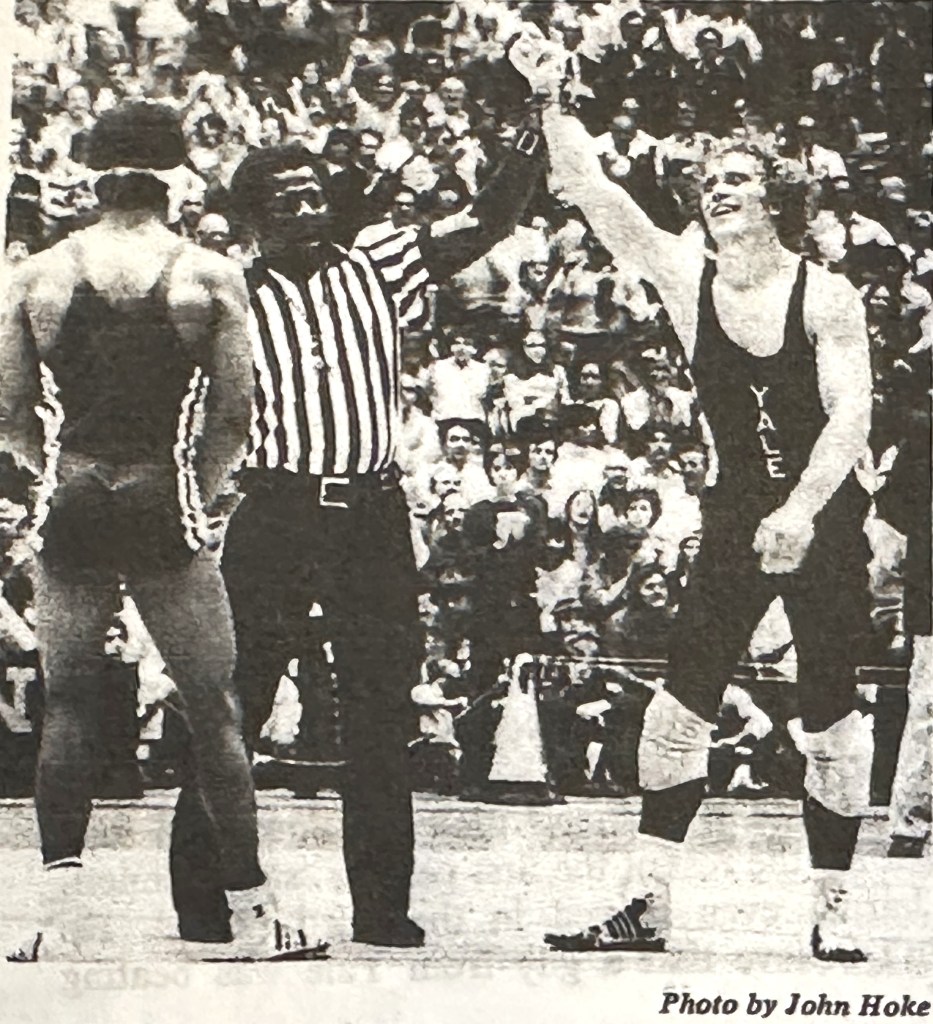

In the finals Bennett faced the No. 3 ranked Andre Allen from Northwestern. Allen’s record included two Big Ten Championships and a first place medal at the prestigious Midlands Tournament that year. Andre Allen had also been a Junior National freestyle champion and placed fifth in the Junior World Cup. Coach Waterman encouraged Bennett: “Jim, ignore the press clippings, just be calm and collected, wrestling YOUR match. You got this!” Coach knew what mattered was showing up as your best self. Bennett had a plan and was ready.

The two wrestled cautiously, protective against any cheap points. That Saturday, Bennett wrestled a smart NCAA Division I finals match. And although Allen held a 2-1 advantage at the end of the second period, Bennett battled Allen from the bottom in the third period. Bennett quickly tied the score with an escape, followed by a solid takedown. He continued his skein of strong leg-riding time, earning an extra point. In the waning seconds Bennett gave up a stall point, on his way to a 5-3 decision in his favor.

Marty Schwartz, captain of the Yale team, commented, “I knew the Northwestern Coach, Ken Kraft, from my high school years in Illinois and I knew Jim could beat Andre, who went to Lane Tech. Bennett had his takedowns, leg rides and slick Granby roll.”

Waterman on Goal Setting

Waterman felt Bennett would savor that win, yet he knew Jim was dissatified in the end. Coach Waterman explained what he knew for sure about this wrestler: “Jim was happy about being National Champion, but he was worried he didn’t do something exactly right. He felt he should have done it better…To my mind, Jim’s the ideal type of athlete. He knows what goals he wants, he knows what he has to do to get them — and does it. Jim does an awful lot of hard work. He’s always finding people to stay late and work extra with him.”

Captain Marty Schwartz chimed in, “Jim keeps to himself a lot. He’s a leader by example. During practice he’s really quiet. A real champion is someone who really hates to lose. Jim dispises losing, that’s what separates him from the rest.”[2]

Coach Waterman opined further, “Jim Bennett will never stand still as a wrestler. He wants to be the perfect wrestler. Jim’s going to go out every match and demand of himself that he wrestle like a national champion or better.“

As a senior at Yale, Bennett moved up a weight class to 150 lbs and again achieved All-American status. He defaulted to Ken Wilson from Syracuse in the finals of the EIWA qualifying tournament and finished second. Bennett sustained a serious knee injury and DNF (Did Not Finish) the EIWA finals match. Going into the NCAAs Bennett, on the strength of his defending champ and runner up at the EIWAs status, was seeded 4th. He beat Ruffin of SIU-Carbondale (4-1) and Tusick of Alabama (9-7), before losing again in the quarter-finals to Ken Wilson (10-7) of Syracuse. (Incidentally, Wilson’s brother, Cliff Wilson, wrestled with Bennett at Yale). In the consolations Bennett defeated Malavite of Ohio Univ. (4-2) and Hitchcock of Cal Poly (10-5) before losing in the consolation finals to Mark Churella of Michigan (14-5). Bennett matched his seed and placed 4th at the NCAA tournament, despite being heavily taped with a torn ligament in his knee, that he sustained during the EIWAs.

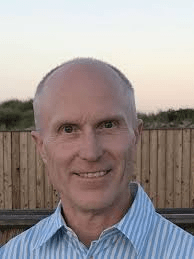

Jim Bennett finished his wrestling career at Yale as a National Champ and two time All-American. He notched a collegiate record of 70-13-1, with 12 wins by pins. Not since Andy Fitch (1959) had Yale produced such a successful wrestler.

Bennett went on to become an assistant wrestling coach at Harvard, while he earned his MBA. During his coaching at Harvard, Bennett trained for the US Olympic team, finishing in the top eight at the US qualifiers in 1980. In 1984, Bennett was elected to the Pennsylvania State Wrestling Hall of Fame, and in 1998, he was elected to the Corry Sports Hall of Fame. Bennett has been a highly successful as a business investor in distressed corporate debt. He also has stayed active in sports for many decades, spearheading the addition of Women Wrestling to the sports scene in the US.

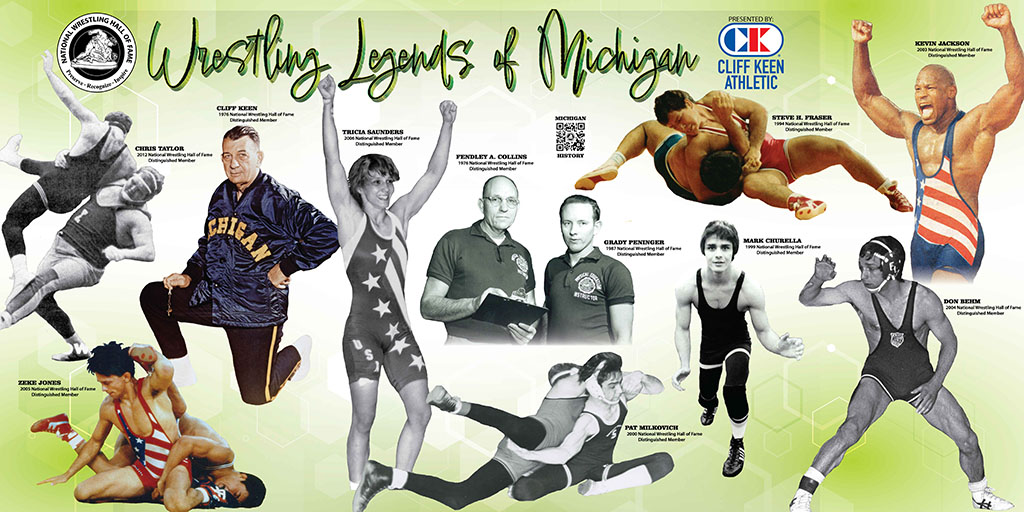

Waterman Earns Michigan Wrestling Hall of Fame Honors 1978

Bert Lee Waterman was a 1950 graduate of Michigan State. He was a former Spartan’s wrestler and a remarkable coach. For his lasting impact on Michigan wrestling, Waterman was elected to join the Hall of Fame’s inaugural class of 1978. Waterman was honored at the local ceremony to the Michigan Wrestling Hall of Fame.

1991 – the Yale Wrestling Program is no longer intercollegiate

Sadly, by the early 1990s the Yale wrestling program was “hanging by a thread.” While other wrestling programs in the Ivy League were flourishing (Cornell, Princeton, Harvard, Brown & Penn), Yale’s program floundered. The pressures of Title IX and the apathy from the tone-deaf administration could not be overturned. In the background was a legion of loyal Yale wrestling alumni, who attempted to apply pressure to the athletic department and administration. The alums even offered to pay for the coaches, the equipment, training staff, and travel, and to endow the program … all to no avail.

Finally in 1991 the varsity intercollegiate program at Yale was dumped and its status was demoted to “club.” The proud 88-year history of Yale collegiate wrestling was laid to rest that year.

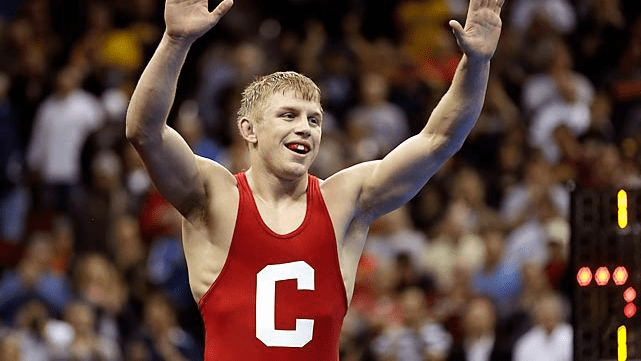

The Rise of Cornell: Dake and Diakomihalis

An interesting footnote to the Yale Story is the fact that another Ivy League university, faced with the exact same Title IX challenges. The difference is that Cornell believed that wrestling, as a discipline, was worthy of support. Why? Because, despite being a “non-revenue generating sport,” Cornellians believed that wrestling held merit and critical recognition through it all. Two Cornell wrestlers, in particular, prove the point that a team does not need many men (or women) to build a nationally recognized program: Kyle Dake and Yianni Diakomihalis.

These two Big Red wrestlers were the first 4-time collegiate champion wrestlers since George Dole of Yale in 1906. Kyle Dake won his 4 NCAA championships competing in four different weight classes (141, 149, 157, and 165 pounds from 2010–2013), becoming the first athlete to do so. The statisticians needed to go all the way back to the record books to find the Dole Brothers. It is important to note that George Dole competed in the Ivy League Era (pre-NCAA era). Dole’s collegiate record of 100-1 is indeed impressive, representing a win rate of 99%, but the competition was not nation wide. Dake’s collegiate record was secured in this century with a vast level of competition from all participating colleges. His collegiate record was 137-4, which is a 97.2% winning rate.

Yianni Diakomihalis had challenges of his own, trying to compete in the era of Covid-19. His career (2018, 2019, 2022, 2023 NCAA titles) elevated Diakomihalis to be one of the most decorated collegiate wrestlers in history. Diakomihalis had a career record of 115 wins against 2 losses, for a 98.3% win rate.

Dake and Diakomihalis are truly two additional wrestlers for the record books. Each continued his wrestling success beyond college and into the international front. Dake’s accomplishments in freestyle wrestling, include four World Championship gold medals and two Olympic bronze medals. Diakomihalis’s accomplishments in freestyle wrestling include winning a 2022 World Championship gold medal at 65 kg, and winning multiple gold medals at other international tournaments. He also won the 2025 U.S. National Championships at 70 kg and has competed in high-level events such as Real American Freestyle.

Two other Cornell wrestlers of note are Travis Lee and Mack Lewnes. Travis Lee was Cornell’s first multi-time NCAA champion and he led the way for more champions ahead. Lee was a two-time NCAA Champion for the Big Red in 2003 (125 lbs) and 2005 (133 lbs). The other Cornell wrestler of note is Mack Lewnes, who was a three time All-American. And although he was never an NCAA champion, he holds one of the most successful grapplers to put on a Big Red uniform. From 2009 to 2011, Lewnes placed 3rd at 165 lbs, and 2nd at 174 lbs. He was just short of All-American status in 2011, when he lost in the round of 12 at the NCAAs.

One can only wonder what Yale wrestling might have achieved, if the University had kept wrestling in its sights as a sport worth supporting. That buried chapter, which could have been written starting 35 years ago by the Bulldogs, will not see the light of day. Too bad for the Eli’s!

References:

[1] https://yalealumnimagazine.org/authors/110) | Jul/Aug 2013

Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.

[2] I made some initial errors in my reporting on wrestling at The Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Preston G. Athey, a Hill School graduate and former Chair of the Board at Hill, is a Yale and Stanford grad and asked me to acknowledge the strong wrestling tradition at The Hill School. With that research in mind, it is worth noting that Coach Frank Bissell served as the school’s head wrestling coach from 1947 through 1973, leading Hill to a remarkable era of interscholastic success, which included 11 straight National Prep championships from 1949–50 through 1958–59. Over the course of that decade, The Hill School had many individual wrestling champions: Andy Fitch is among them. Thank you for the pointer, PGA.

[3] The too subtle pun is that Larry Pickett’s wrestling tenure was an uphill push during the War Years, when all who went to war and returned for a degree are honored as the class of ’45W. While comparing a wrestler to a warrior is a stretch, and not meant to offend, Larry Pickett fought and lost in his final wrestling match, making the comparison somewhat apt. The most famous warrior we know with the name Pickett is Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett from the Battle of Gettysburg. Pickett’s Charge was a massive Confederate infantry assault on July 3, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg. During that battle roughly 12,500 men advanced nearly a mile across open ground to attack the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. The charge was decisively repulsed by the Union army with devastating losses.

Wartime Impact: Pickett’s Charge marked the high-water mark of the Confederacy and the furthest advance into Union territory. The loss by the Confederacy shattered Robert E. Lee’s offensive capability in the North. After Gettysburg, the Confederacy was largely forced onto the defensive, making the battle a turning point in the Civil War.

[4] Many of the citations and images in the post are from the Yale Daily News, a long-standing campus newspaper, which has some important wrestling articles in its archives.