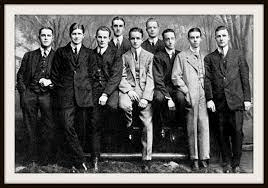

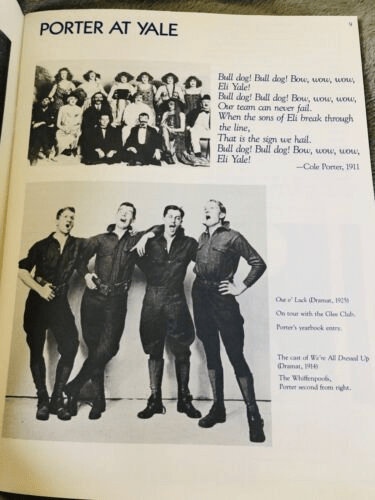

Cole Porter (second from right) on Yale Fence with Whiffenpoofs, 1912

Witness Post: Vanderbilt and Porter at Yale

In 1975, at the end of my junior year at Yale, I was called into the Dean of Morse’s office for a discussion. The last time we had met, the Dean had been very disappointed that I had refused to live for the spring term in the “Morse Annex” past the Gym, off campus with some other male Morse students. The Dean loosened the rules and had wanted me to stay in the now coed dorm. I revealed that I didn’t feel it would be safe for the Morse female, so I turned down the offer. My decision had hinged on the fact that one month prior a female student had been raped at an apartment next to the Annex.

At this next meeting, to my surprise, Dean Eva Balogh, seemed to have forgiven my housing change. Instead she asked me to consider serving as a freshman counsellor for incoming students in the class of 1979. Freshman Counselors were traditionally grad students. Ours was apparently the first undergraduate class to be invited, as seniors, to step up to the task. Stunned, I did not know that she felt that I could handle the responsibility.

If I said YES, it would mean giving up a Morse tower suite with a bird’s eye view of Claus Oldenburg’s “Lipstick Elevated on Caterpillar Tracks,” in return for the best view of Yale’s Old Campus. In addition to providing room & board, it was a big commitment. I also had to make room in my busy schedule to be a reliable source of freshman-year support.

Lipstick Elevated on Caterpillar Tracks, sculpture by Claus Oldenburg, Yale ’50

Vanderbilt Hall on Yale’s Old Campus

Vanderbilt Hall, in those years, had been the housing for all of the women on campus. And it remained so until the middle of the 1970s decade. If anyone wanted a date with a female Yale student, you had to understand parietal rules and find your way to the guard station, located at the then glassed-in entryway to Vanderbilt. Once there, you had to get permission to visit your date, signing in and out of the hall on an appointment ledger.

My junior year visit to the famous Vanderbilt Suite, as it was known, was in early spring of 1975. The former all-women’s quarters had converted to co-ed accommodations. I visited the dorm with my future roommate, David Nierenberg. We knew each other by sight, but we were in different classes and majors (David-’75 Directed Studies, Henry-’76 Educational Psychology) and we had different circles of friends. In the fall of 1975, David would be joining the Yale Law School class of 1978. On that spring afternoon we walked up the spiral staircase to the second floor and soon spotted a blue sign on the door: its white lettering announced that Cole Porter, Yale Class of 1913, had lived in that room during his senior year.

Dean Balogh had given us the key to the prized Suite. When we walked into the room and viewed the space, simply put, it was magnificent. Having spent a few years in “psycho singles” at Yale (Bingham Hall and Morse College), this suite was palatial: a large living room, mahogany panelled walls, rose marble fireplace, gold leaf plaster upper walls, parquet floor, 12 foot ceilings with decorative mouldings, and two separate bedrooms. (The rose marble was lovely, however it was purely ornamental, as the University did not want students to use fireplaces and possibly set the historic building ablaze.) There was a love-seat built below the four windows that overlooked the rest of Old Campus. The walnut stained armoir and room furniture had plenty of drawers and closets for each of us to store our belongings. We were amazed at our good fortune.

Walking back to Morse for lunch that day, David mentioned the rumor that the Vanderbilt Suite was always reserved for heirs of Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose grandsons had attended the college. We were fortunate to be allowed to stay in the suite, because we heard about the rejection of a Vanderbilt great, great, great grandchild, or so the story goes. Their loss was our gain.

David and I thoroughly enjoyed that year at Yale, hosting many parties in the Suite for our Morse freshmen, who shared both the Vanderbilt entryway and an adjacent entryway in McClellan Hall. David had a terrific sound system and a host of hit records, which made for some great line dances, “orange death” parties and evening storytelling. David was also a wise counselor for the freshman. We all learned a lot by listening to the guidance he offered to his half of the male freshmen in Vanderbilt and the bevy of female frosh in McClellan who sought advice. He also provided more than his share of counseling to the students assigned to me, when I was off with wrestling practice, singing concerts, term papers writing and playing lacrosse.

As I reflect on that time together, two names were attached to our room: Porter and Vanderbilt. Yet, I was curious as to the stories that wove these families into the history of Yale?

What a coincidence to be living in a suite with connections to these two important characters in the life of commerce and musical theatre in U.S. history. This Witness Post is an effort to unravel the two families, so different, yet so American, and to discover what they have to say to us today. It is also a thank you to our Morse Dean Eva Balogh for having faith in us and making the introduction.

The Vanderbilts

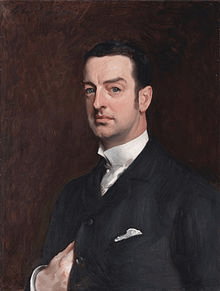

Cornelius “Corneil” Vanderbilt II, 1843-1899, portrait by John Singer Sargent

In the Vanderbilt family, there is a child named Cornelius in nearly every generation, so to reduce confusion, nicknames are appropriate. Corneil, as he was known, was the son of William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) and Maria Louisa Kissam Vanderbilt (1821-1896), and grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877). Corneil was born on Staten Island, New York, and he spent the majority of his working life on the New York Central Railroad. He and his wife, Alice Claypoole Gwynne Vanderbilt, had seven children together. By that time the Vanderbilts were already famous as a solid American family which gained prominence during “The Gilded Age.”

Vanderbilt Early Success

The family’s early success story began with the shipping and railroad empires of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. From there, the family expanded into a series of other businesses, and eventually into philanthropy. With their newfound wealth, Cornelius Vanderbilt’s descendants went on to expand their influence beyond Staten Island to build grand mansions on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan; luxurious “summer cottages” in Newport, Rhode Island; and palatial homes, like Biltmore House in Asheville, North Carolina, and Berkshire Cottages in Lenox and Stockbridge, Massachusetts. They were rich after Croesus and before the Rockefellers and Beineckes.

Biltmore Estate, Asheville, NC

At one time the Vanderbilts were extraordinarily wealthy. The patriarch, Cornelius Vanderbilt, until his death in 1877, was recognized as the richest man in America. The Vanderbilts’ family wealth and social prominence lasted until the mid-20th century, when ten (10) of the family’s great Fifth Avenue mansions were torn down, and most of the estates were either sold at auction or turned into museums.

Vanderbilt and Yale?

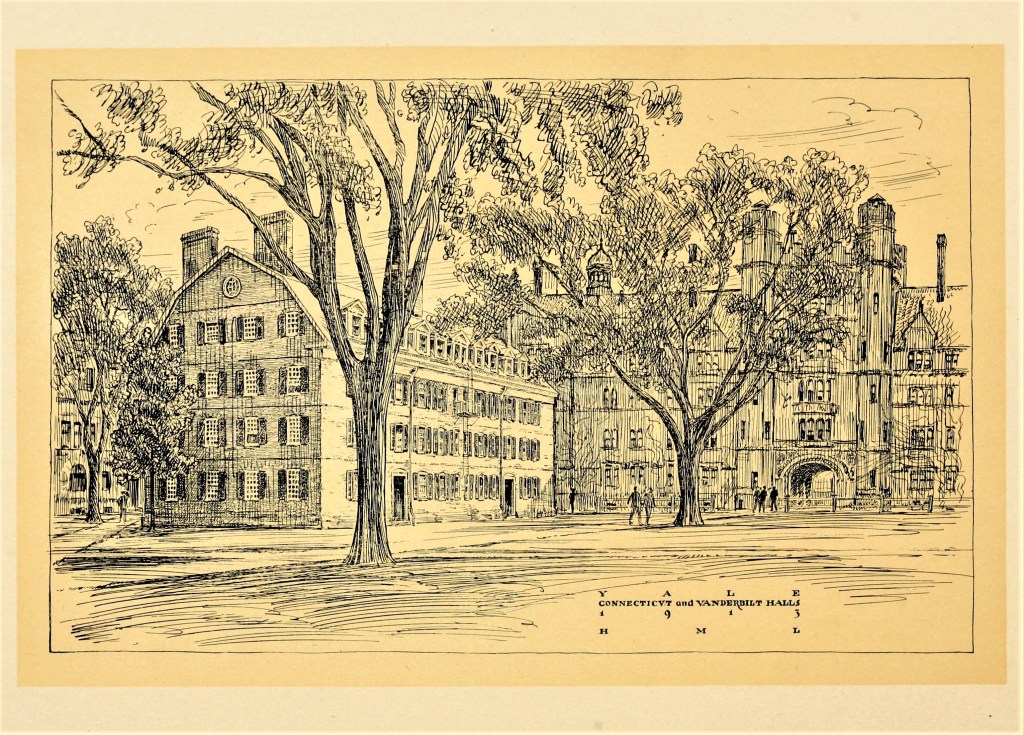

Vanderbilt Hall is modelled after one of the buildings of Oxford University, England, in accordance with the wishes of Willie Vanderbilt, formerly of Yale, Class of 1893.

As the story goes, in 1892, when Corneil and Alice Vanderbilt, Willie’s father and mother, were visiting with him at Oxford University, Willie pointed to a prominent building and said to them, “If I were to build a dormitory, it would be just like that!” Within one year of this proclamation, Willie was dead. He died of typhoid fever, which he contracted from a public drinking fountain in New York City. In light of his fatal illness, the family felt that Willie’s architectural proclamation seemed prophetic. Cornelius Vanderbilt II decided he wanted to build a dormitory at Yale, in the image of that Oxford dorm, and to name it after his son, as a memorial.

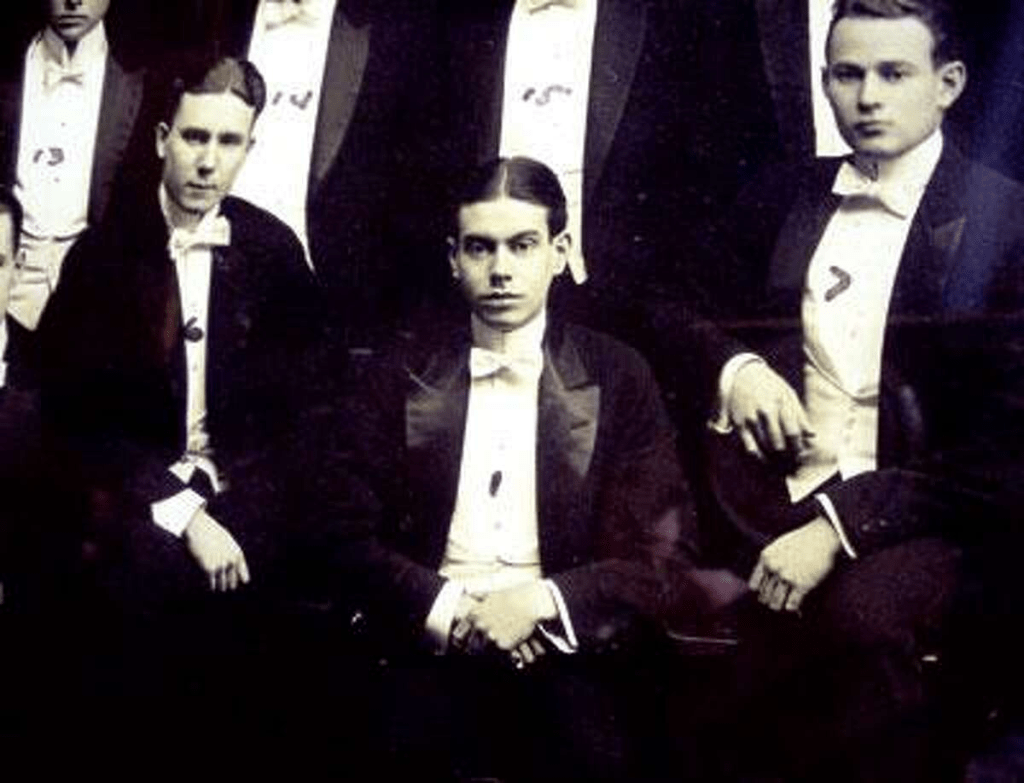

Image courtesy of the HathiTrust Digital Library, Yale University, “The Yale Banner,” 1913 – 1914

Some Vanderbilt Hall Building Details

The architecture of the Vanderbilt dormitory at Yale is Gothic, with a touch of the Renaissance. It consists of a main building and two wings. It is four stories high, with a basement, and has two entrances from the courtyard and one from the campus side. The campus-facing side has an archway and central tower. The tower was designed to be five stories high. The specifications for construction of the tower stated that the arch was made of iron and marble forming a large arch entrance 12 by 14 feet, with marble seats in recesses on each side.

According to architectural plans, most of the suites of rooms consist of a study and two sleeping rooms. Most of the study rooms were to face the court and have three windows. Many of the rooms facing the quadrangle have dainty oriel windows. Private vestibules were constructed in each apartment where practicable. Each room’s study area has an open fireplace and every suite two spacious closets. On each floor will be a bathroom. The building was designed to be fire-proof, and in this respect it was the second of its kind at Yale, the Chittenden Library being the other. The dormitory was designed to be heated by steam, conducted in pipes from the new boiler system in the rear of the old gymnasium; hence the truth and mythology of the Yale “steam tunnels” was born.

The designer of the building is Charles C. Haight of New York, who also designed many of the Columbia College buildings, several of those of St. Stephen’s College, and the Adelphi, in Brooklyn. The dormitory construction was hurried along and the dormatory was finished and ready for occupancy by September, 1894. Its name, Vanderbilt Hall, was to be inscribed above the arch entrance.[6]

Vanderbilt Hall, Yale University Old Campus

Ironically, in spite of it’s grandeur, the architect stated emphatically that the dormitory was designed for the “middle class, and not the rich upper class, as might perhaps be inferred from its aggregate cost.” The total construction costs were $1 million (approx. $35 million in today’s dollars). Willie Vanderbilt, in whose memory the dormitory was erected, had a younger brother, Cornelius “Neily” Vanderbilt III, who was in his junior class at Yale, while the new dormitory was being constructed. To this day the impressive building has a lavish interior, built to compete with the fancy private apartments and dormitories that lined the opposite side of Chapel Street at the time.[2]

Perhaps the rumor of Vanderbilts’ claiming dibs on the Suite goes back to Neilly Cornelius III[3], Yale Class of 1895, who may (or may not) have taken advantage of the opportunity to live in his father’s new dorm room, which had been imagined and named in honor of his deceased older brother.

Cole Porter & Yale

Cole Porter (1891-1964) as a College Man[4]

Born in Peru, Indiana, on June 9, 1891, Cole Porter was the son of Kate Cole and Samuel Fenwick Porter. The future composer of Kiss Me, Kate got his first exposure to music from his mother. Mrs. Porter introduced young Cole to the piano and the violin. By the time he left for Worcester Academy at age 14, his appetite for lyric writing had been whetted by his pharmacist father who harboured avid interests in classical languages and 19th-century romantic poetry.

After a summer of touring Europe in his senior year at the Academy, Porter arrived at Yale in the fall of 1909. He was soon to meet his classmates W. Averell Harriman and Sidney Lovett[5], among others. Porter majored in English, minored in music and studied French. He also received academic credit for singing in the University choir.

Porter was also heavily involved in extracurricular activities including music and cheerleading. During the football season he achieved an additional measure of campus fame for writing the fight songs, “Bull Dog” and “Bingo Eli Yale.” Porter added to his popularity by singing in the Glee Club, and writing suave, audacious musical comedy scores for the play (Cora and The Pot of Gold). Plays were often performed as part of the initiation ceremonies at his fraternity, Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE), and for the smokers put on by the Yale Dramatic Association.

Porter in the Vanderbilt Suite

For his first three years at Yale, Porter roomed alone. But as a senior, he and Humphrey Parsons moved into room 31 Vanderbilt, the sumptuous suite over the archway of Vanderbilt Hall. Porter and Parsons had become friends as members of the Glee Club, and as seniors they shared its leadership, Parsons as Manager and Porter as President. Porter also got top-billing as the star of the Glee Club’s month-long annual Christmas tour, which took the singers across America by luxury train.

The documentary evidence of Cole Porter’s days at Yale is relatively thin, during those carefree, pre–World War I days. By no means were all of those days spent singing. One archive of material has eleven of Porter’s class notebooks, comprising more than 700 pages. Most of the entries are in pencil, and many are written on both sides of a sheet. One notebook includes review materials for Sophomore English (B5) and mentions authors such as Spenser, Milton, Bacon, Pope, Addison, Steele and Swift. Two relate to a course entitled, “English Poets of the Nineteenth Century” (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats, et al.), which Porter studied during his junior year (1911–1912). From his senior year there are notebooks on physiology, “French Literature of the Seventeenth Century,” “Tennyson and Browning,” and of course, Shakespeare.

Porter, far left, with his Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) fraternity at the Yale Fence

Among the attributes, that set these notebooks apart from the normal run of undergraduate scribblings of the day, are page after page of Porter’s remarkably skilled cartoon drawings. Many of them are of elegant women dressed in the sleek fashions of the day. He also penned many flamboyant variations on his own signature. A few of the notebooks also include a variety of music exercises and lyric sheets, some of which provide hints of later compositions. There is also a typescript of Almet F. Jenks Jr.’s libretto for The Pot of Gold, Porter’s most important and best-preserved Yale musical, and his own copies of three of his earliest published songs, “Bingo Eli Yale,” which he wrote for the 1910 football song competition; “Bridget,” also from 1910; and “Flah-Dee-Dah” (1911), the first “lost” Porter song to come to light since the discovery a decade ago of many of his manuscripts in a Warner Brothers warehouse in Secaucus, New Jersey.

Digging deeper, Porter’s college notebooks and papers are a fragment, outline, and incomplete cast list for an unfinished, somewhat fantastical musical fable about a circus troupe complete with clown, bareback rider, snake charmer, fat lady, skeleton, and manager. There are also early versions of lyrics for “Scandal,” from The Pot of Gold, “Maid of Santiago,” and “In the Land Where My Heart Is Born,” from The Kaleidoscope. William Lyon Phelps, the legendary English professor and Porter’s mentor in The Pundits, congratulated the Yale Dramat after seeing The Kaleidoscope for “having one man who is a real genius and who writes both words and music of such exceptional high order.”

Porter’s own reactions to Phelps and his famous course on Tennyson and Browning are amply documented in one of the notebooks. For example, Porter noted that Tennyson’s “The Princess” had an “excellent libretto for comic opera,” and he responded raptly to Phelps’s sonorous utterances on “In Memoriam,” “Maud,” and many of the shorter poems as well. However, when Phelps turned to Tennyson’s late plays—Harold, The Cup, and The Falcon—Porter’s thoughts were elsewhere, and he diverted himself by filling his notebook pages with words and music for songs entitled, “Exercise” and “We Are So Aesthetic.”

Yet of all the notebooks surely it is the pair for the Shakespeare course, B7 (described as “a rapid reading of all the authentic Bard plays”), that provides the greatest insight into the way songwriting invaded Porter’s academic life, and eventually emerged onto the stage.

For all his precocity and his early triumphs as an undergraduate, Porter was dogged after graduation by a series of disappointments that delayed, if only briefly, what seemed to be an inevitable rise to the top of his profession. After leaving Yale, he studied briefly at the Harvard Law School, switching at the law school dean’s suggestion to the Harvard School of Music. That training, however, was not enough to make a success of Porter’s first Broadway show, See America First (1916), which closed two weeks after its New York opening.

In June 1917, soon after the United States entered World War I, Porter sailed for Europe to work with the Duryea Relief Organization. Within a few months he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and for a time was attached to the American Embassy in Paris, where he met and married the elegant divorcée Linda Lee Thomas.

There have been many stories over the years about the marriage of Linda Lee Thomas, the socialite from Cincinnati, and Cole Porter. Most tales were calling it a sham and trying to smear Porter as a homosexual hiding in marriage. But many of their closest friends felt that they always had a happy and supportive marriage and deep affection for each other. The record shows that they were married in 1919 and stayed together until her death in 1954.

From World War I until the late 1920’s, the Porters lived primarily in Europe, mostly in Paris and Venice, and they traveled widely. However, Porter’s years as a playboy-expatriate, when many thought he was doing little but giving and going to parties, afforded him both the distance and the stimulation to develop his own distinctive artistic style. Nevertheless, while the songs he wrote during those years were presented in such revues as Hitchy-Koo of 1919, Mayfair and Montmartre (1922), Hitchy-Koo of 1922, and Greenwich Village Follies, in 1924, the critics response to his work at the time was not enthusiastic.

Linda Lee Thomas and Cole Porter, married in Paris 1919

So discouraged was Porter about his career at this point that he was prepared to abandon songwriting altogether. Fortunately, his good friend Monty Woolley, the director of the Yale Dramat, intervened, and Porter reluctantly agreed to submit three songs for Out O’Luck, a comedy melodrama about American doughboys in France. The show’s success on the Dramat’s Christmas tours of 1925 and 1926 helped Porter recover the self-confidence that had eroded so badly since graduation.

Henry C. Potter ’26, who played the lead in Out O’Luck, recalled Porter’s mood at that time: “I remember well, one evening ‘after hours’ when those of us in the Dramat sat around with Cole, singing and doing little skits, imitations of Al Jolson and so on. I did an imitation of some currently popular, vaudeville ‘sob ballad’ singer. When I finished, Cole laughed heartily; then his face grew somber and he said, ‘But do you know? I wish to God I could write songs like that.’ Thank God he didn’t. But not too many years after that evening along came ‘Night and Day’ and all the glorious rest. And we Yale ’25 and ’26ers have always thought that perhaps we had helped him a little.”

Indeed they had. Many great shows and songs followed—topped perhaps in public esteem by Anything Goes in 1934, Kiss Me, Kate in 1948 and Can-Can in 1953, as well as such classic Porter tunes as “Begin the Beguine” and “In the Still of the Night.”

Even after the terrible riding accident that crushed both his legs, when a horse fell on him in October 1937, Porter continued to write his amusing, exhilarating, often poignant songs. He welcomed communication with his Yale friends and classmates over the years and was cheered up considerably when they would come by for some a cappella renditions of the songs he had written in college.

Porter would no doubt have been especially delighted to know that the school books, songs, and sketches that he had taken with him on his summer visits with the Parsons in Maine have found a new home alongside the papers, books, and recordings which he bequeathed to Yale College on his death in 1964. That was only four years after Yale had saluted him with an honorary degree bestowed at his apartment in New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The citation read, in part:

“Cole Porter: ‘As an undergraduate, you first won acclaim for writing the words and music of two of Yale’s perennial football songs. Since then you have achieved a reputation as a towering figure in the American musical theater. Master of the deft phrase, the delectable rhyme, the distinctive melody, you are, in your own words and in your own field, the top … Your graceful, impudent, inimitable songs will be played and sung as long as footlights burn and curtains go up.’“

Cole Porter and his instrument

Fans of American musical theater spent much of 2013 celebrating the centennial of Yale’s most famous minstrel, Cole Porter, who graduated from Yale College in 1913. Artists as diverse as Thomas Hampton and U2 recorded his songs for the occasion, and such institutions as the Smithsonian, the Indiana Historical Society, and the U.S. Post Office have created their own special tributes.

Two Family Conclusion

Tying the Vanderbilt family and Cole Porter into one Witness Post is a challenge. The connection of the two families does not have a consistent theme. The only through-line is Suite 31 Vanderbilt Hall. That’s where David Nierenberg and I fit in. We lived at Yale in an era that was gradually opening for gay and lesbian rights. Cole Porter must have had his challenges hiding his sexual preferences, while at Yale. It has always been tough. Our Dean, Eva Balogh, was living in the Morse Tower with the College’s former Dean, Brenda Jubin — two brilliant Yale professors. They have their own stories of scholarship and prejudice that may have been ingrained in higher education and society in that era. Porter was finding his way as a gay man before, during and after World War I; how much more challenging might that life have been for him and Linda Lee Thomas in post-Depression New York!

Cornelius Vanderbilt Sr. was not a Yale graduate. His only connection was through his great-grandchildren. He had other colleges in his sights, one even adopted his nickname as their mascot, The Commodores.

Central University (Nashville, Tennessee) received a gift of $1 Million from Vanderbilt, who designated his dollars toward the school’s endowment. The year was 1877. Vanderbilt gave his gift in the hopes that his financial support would amplify the greater work of the university to help the deep South heal from the sectional wounds inflicted by the Civil War. Vanderbilt knew in his bones of the trauma and bloodshed of war and he put his money where his mouth was. The Commodore died shortly after the gift was received. The school trustees renamed Central U. to Vanderbilt University in his honor.

The Vanderbilts respected colleges, and loved their families. Corneil Vanderbilt II did what he felt was the right tribute to Yale. He wished to honor the life of his deceased son. Vanderbilt had faced death in his own family before. He must have had profound heartache when he gave his gift to Yale. That $1 Million did not earn his family another college with the family name on it. The gift was not about naming rights or endowments — it was about profound sadness in his heart for the lost, potential greatness for his gifted young son.

No matter how you juxtapose the stories of Vanderbilt Hall and Cole Porter, the family names showcase titans: Cornelius Vanderbilt, a titan of industry, and Cole Porter, a titan of musical theatre. They both ruled their realms. They both knew the tragedy of death and the horrors of War. Yes, they both had their detractors. Both had their accolades and their hardships. Through their own tenacity, they survived beyond their mortal lives in the memories of those who knew them well and loved them, even in smaller measures if the love were for their music and their money.

The silver lining for Yale students today (and yesterday, like David Nierenberg and me) is that we share a common bond with these men and their names. Yale University has Vanderbilt Hall as a magnificent dormitory for its safe student housing. Current freshmen can enjoy an enviable view of Old Campus, just as the first female students at Yale did. Cole Porter’s plaque still hangs in the hall and it calls students to look up the stories of the man who wrote “the best canine College cheer of all time.” (Take that Georgia!) He also penned some of the most memorable songs of his era (a complete Cole Porter song list is below).

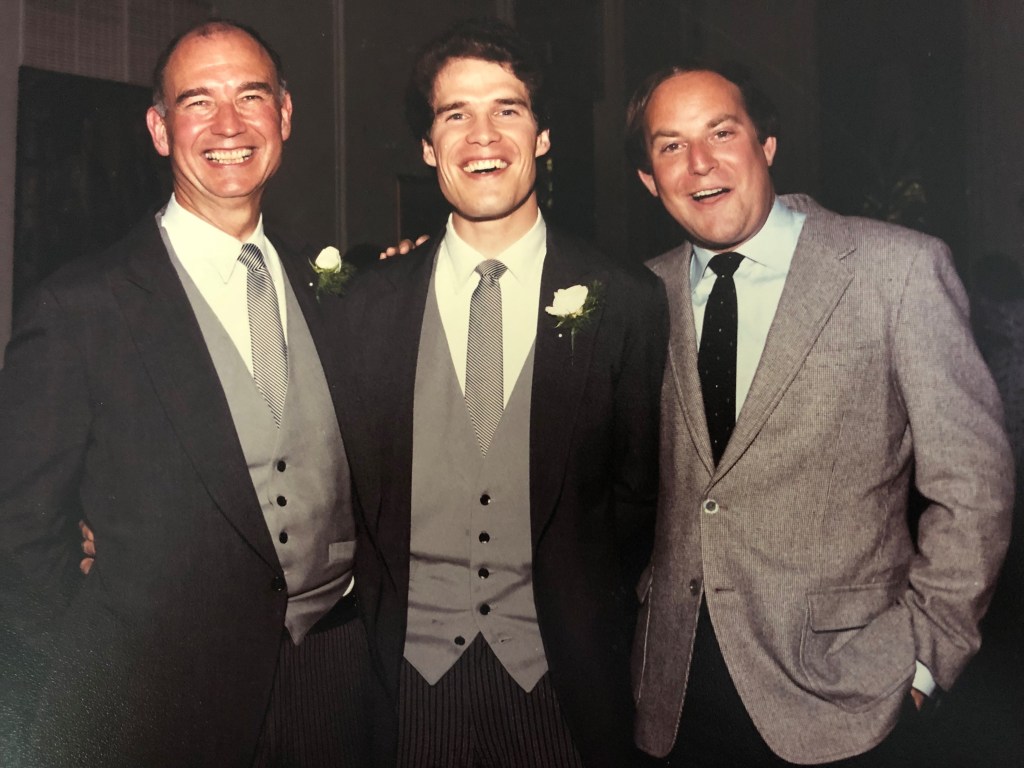

For now this Witness Post, above all, is a thank you note to Dean Eva Balogh for having the generosity to put us in Suite 31 Vanderbilt Hall. Many years later, David Nierenberg and his wife, Patricia, honored me as the Godfather of their son, Jacob. Years later still David invited me to serve as a business partner in his financial firm on the West Coast. Dean Balogh changed the trajectory of my life and for that I am eternally grateful.

Laurie Hooper, Henry Hooper, David Nierenberg at Henry’s wedding in 1984

Notes and References:

[1] Recollections of my time in the Vanderbilt Suite, Yale University, 1975-1976.

[2] Excerpt courtesy of the New York Times, Times Machine, “Vanderbilt Hall at Yale,” Sunday, August 20, 1893.

[3] Neily Vanderbilt was a Brigadier General in the American military, and an inventor, engineer, yachtsman and a Yale man, Class of 1895, and two other Yale degrees in 1898 and 1899. Cornelius “Neily” Vanderbilt III (September 5, 1873 – March 1, 1942). He may be the long lost Vanderbilt whose ghost still pines away to live in the Yale Suite, named in honor of his older brother.

Cornelius “Neily” Vanderbilt III (1873 – 1942)

[4] Rather than construct from thin air some of the wonders in the life of Cole Porter, I read a story from the Yale Alumni Magazine from 2012 that fills the bill. I take major sections of the article here to describe this marvelous, creative genius. http://archives.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/92_11/coleporter.html

[5] W. Averell Harriman (1891 – 1986) was an American Democratic politician, businessman, and diplomat. The son of railroad baron E. H. Harriman, he served as Secretary of Commerce under President Harry S. Truman, and later as the 48th governor of New York. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1952 and 1956, as well as a core member of the group of foreign policy elders known as “The Wise Men.”

Augustus Sidney Lovett (1890 – 1979) was the Second University Chaplain at Yale and the Pastor of the Church of Christ in Yale from 1932 – 1958.

[6] There are lots of legends spread by the tour guides about Vanderbilt Hall. The first of the tour legends is that Vanderbilt’s architect, Charles C. Haight, originally intended the building to face the interior of Old Campus. However, during construction the builders poured the foundation while reading the plans upside down, resulting in it unique orientation facing the Chapel Street.

The second and more popular myth is that Vanderbilt was selected to house the first Yale class of women as an all-female dorm. But a Vanderbilt heir who entered Yale at the same time had other ideas. According to the legend, he supposedly sued Yale for the right to live in the Vanderbilt suite. Yale backed down and he moved in, calling himself the “luckiest man on campus.” The story concludes with the heir finding his future wife among his female neighbors.

A 1998 Yale Alumni magazine article actually debunked these two myths, but for many they are an ingrained part of Yale’s tour guide mythology.

[7] Songs by Cole Porter

Shows listed are stage musicals unless otherwise noted. Where the show was later made into a film, the year refers to the stage version.

NOTO BENE: a complete list of Porter’s works is in the Library of Congress (see also the Cole Porter Collection).