Witness Post: Doppler Effect

Lying on a hospital bed, listening to my own heartbeat, I felt helpless. At my side was an electrophysiologist trying to measure the size of my heart’s upper chambers. “The echo from this cardiac ultrasound bounces off the chambers of your heart and we use the sound patterns to measure your heart,” versus the average chamber size for someone your size and age. “Like the Doppler Effect?” I asked. “Yes, exactly.“

Little did I know, but that echo cardiogram was also measuring the blood flowing toward and going away from my heart. I was in atrial fibrillation (AFib) at the time, as I seem to be constantly, so who knows what to expect next?

What does the sound of pulsing blood have to do with it? The heart is a pulsing muscle after all, so digging deeper into the Doppler Effect seemed in order.

It’s All About the Frequency of the Wave

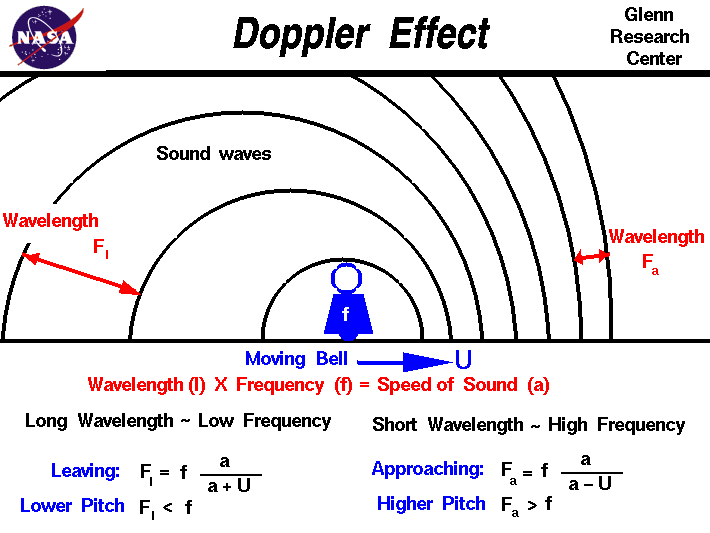

The Doppler Effect (aka Doppler Shift) is the change in the frequency of a wave in relation to the observer of that wave. In all cases the observer, believing they are stationary, is actually also in motion relative to the source of the wave (think, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity). The Doppler Effect is named after the physicist Christian Doppler [1], who first described the phenomenon in 1842.

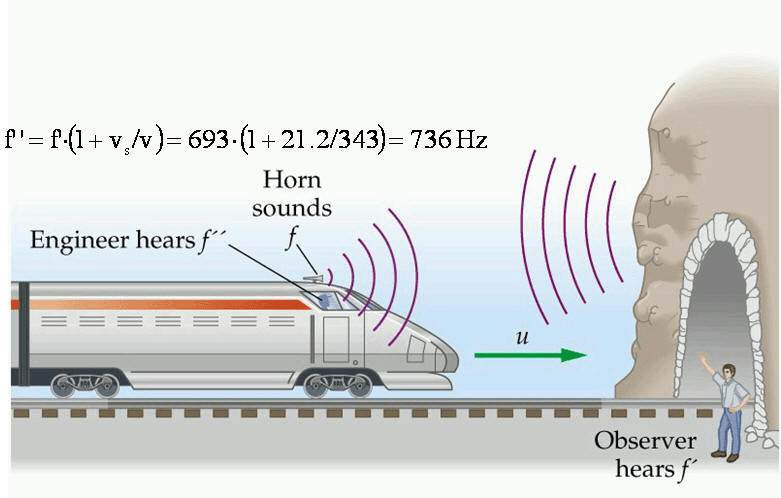

A common example of Doppler Shift is the change of pitch that we hear, when a train is heading toward us, and then there is a change in sound as it recedes from our location. It happens with ambulances, cars, horns, and other changing sources of sound. There seem to be three phases of the sound, 1) the sound as the source approaches, 2) the sound as it is upon you, and then 3) the sound as it is heading away. Compared to the emitted frequency, what we hear is a higher frequency during the approach, identical at the instant of passing by, and a lower frequency during the recession of the source.

When the source of the sound wave is moving towards us as the observer, each successive cycle of the wave is emitted from a position closer to us than the previous cycle. Hence, the time between cycles is reduced, meaning the frequency is increased. And just the opposite, if the source of the sound wave is moving away from us, each cycle of the wave is emitted from a position farther from us than the previous cycle, so the arrival time between successive cycles increases, thus reducing the frequency.

Copying the content from Wikipedia on the more important aspects of the heart and the Doppler Effect, I have cut and pasted the following paragraph. The notion of sound propagating in the heart and moving faster than the speed of light are a bit beyond my pay grade:

“For waves that propagate in a medium, such as sound waves, the velocity of the observer and of the source are relative to the medium in which the waves are transmitted. The total Doppler Effect may therefore result from motion of the source, motion of the observer, motion of the medium, or any combination thereof. For waves propagating in vacuum, such as electromagnetic waves or gravitational waves, only the difference in velocity between the observer and the source needs to be considered. If this relative speed is not negligible compared to the speed of light, a more complicated relativistic Doppler Effect arises.” [3]

The next medical hurdle to leap is to determine how to corral the AFib. What I want is for my heart to function, so that it gives me the length of quality living, stroke-free, that I deserve.

One story that may be worth a separate Witness Post is the story of Geoff Piel, who was a school mate and fellow SOB at Yale. Geoff asked the singing group to be part of his physics class at Southern Connecticut College. We walked into his classroom, sang our version of “Blues in the Night,” and Geoff explained the musicality in concert with the Doppler Effect. That will be a good one.