Two Spirit Myths: Appeal to the Great Spirit

Sculpted in 1908 by Cyrus E. Dallin (1861-1944) this statue pictured above is entitled “Appeal to the Great Spirit” and was cast in Paris, France in 1909.[1] The purchase of the statue was funded by a gift to the Boston MFA by Peter C. Brooks and others in 1913.

Many works of public art commemorate specific events or military heroes. Here, however, an anonymous, unarmed man raises his head and hands skyward, as though in a moment of prayer.

Mounted on a horse, riding bareback and wearing a feathered headdress, this figure appears to be a Native American man from the Great Plains. Why is he in Boston, in front of the MFA?

In the early 1900s, Cyrus Dallin, a white artist trained in Boston and Paris, made his name sculpting Indigenous equestrian figures like this one. Many statues were cast in bronze and became prominent works of public art. Hoping to support Dallin, then a local contemporary artist, the MFA’s leaders installed “Appeal to the Great Spirit” at the Huntington Avenue entrance in 1912 – and while they did not plan for the sculpture to remain in front of the building permanently, it has stood here ever since.

This sculpture has become an icon of the Boston MFA, beloved by generations of visitors.

But for some, it represents a painful “vanishing race” stereotype – a lone Native figure, dressed in a mix of Lakota-headdress and Navajo-style regalia – and erases the stories of living Indigenous peoples, especially those here in Boston. There are many Native Tribes who lived on the Land we call Boston; they include the Pawtucket (or Penacook), the Massachusetts, the Wampanoag (or Pokantot), the Nipmuck and the Pocumtuck. Every white immigrant to this country is challenged now to reckon with this complicated history.

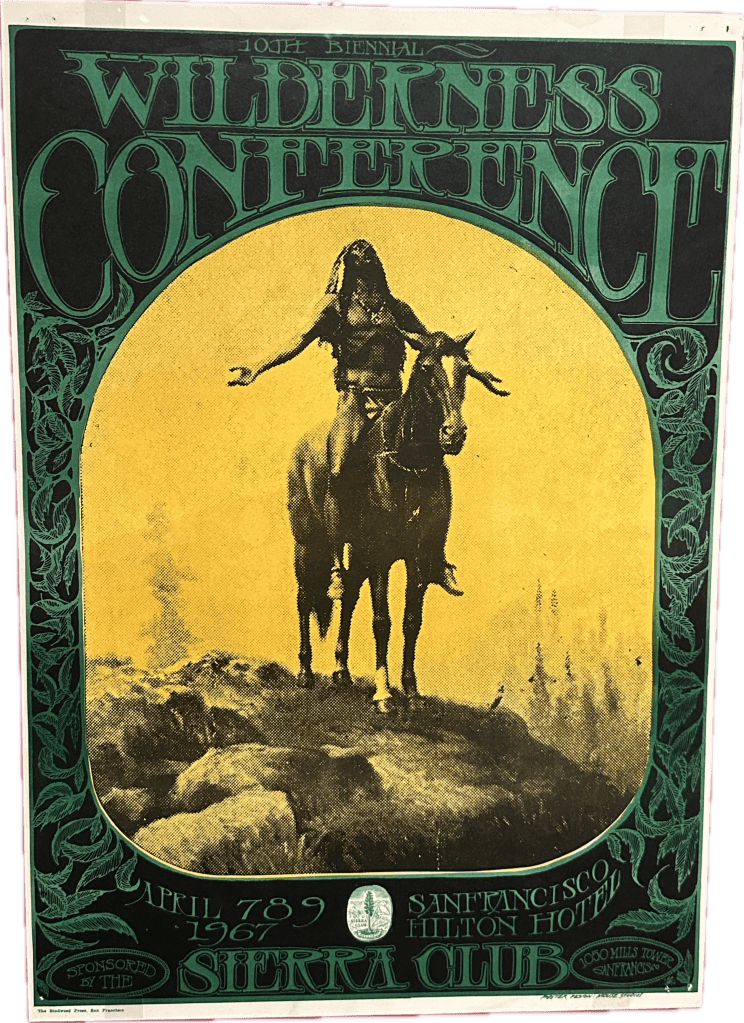

Poster: Sierra Club’s biennial Wilderness Conference held for 3 days in San Francisco April, 1967

In June of 2025, my wife, Tracy had a conference at the Phoenician in Arizona. We flew there ahead of a presentation she was making on “Words to Use, Words to Lose” to the executives of Sanofi, the French vaccine manufacturer. After an early morning hike up Camelback Mountain (adjacent to the hotel grounds), I took a LYFT ride to Old Town Scottsdale and browsed around the shops.

My first stop was The Museum of the West, which featured fabulous collections of Native American art and Native Culture, mostly pre-colonial. Another section had works of art decidedly focused around the Lewis & Clark Exhibition’s Corp of Discovery. The museum was well worth the trip.

And there amidst the Wild West artifacts, books, armaments, and statuary was a bronze, about 4 feet tall, featuring what looked to be the same statue from the Boston Museum. As powerful as it was to witness in the tarnished and weathered version of the Dallin statue in the Boston plaza, this smaller statue was equally evocative of the Great Spirit. [2]

Images of the bronze statues at the Scottsdale Museum of the West (2025)

______________

References:

[1] The image of the bronze was taken in 2023, 111 years since the statue was placed at the Huntington Street entrance. The language from plaque in front of the Boston MFA is repeated above with near exact wording. The Lakota dress, including braids, headdress, loin cloth and moccasins, are complemented by the Navajo bead necklace with the Naja crescent.

[2] These images are from the Scottsdale Museum of the West in Arizona, June, 2025. Interestingly the statue excludes the Naja at the bottom of the warrior’s necklace. It is replaced by some non-descript beads. The smaller statue does includes the same horse and the Lakota rider has all of the other powerful qualities of the larger statue: braids, leather moccasins, headdress, loin cloth, and up-lifted arm positions. There is the same feeling for the viewer of honor offered by the rider to the divine.