River Rafting: Huck Finn & Jim

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been among my favorite stories since re-reading it in college. The novel was part of an American Studies class under the gentle hand of Professor Sydney Ahlstrom at Yale [2].

Professor Sydney E. Ahlstrom [3]

Instead of exploring the text as a childhood adventure story, the Twain novel came alive as an allegory for many important American themes: independence, faith, family, adventure, prophesy, racism, slavery and education. Professor Ahlstrom clarified some hidden meanings of the book in ways that were astonishing. Like a preacher “cracking open the word of sacred text,” Ahlstrom read Twain’s language aloud to class and he explained its meaning, in detail. The vernacular, which was hard to fully grasp, became crystal clear as he told the stories of the different religious and cultural traditions that had shaped American thought at that time. Unable to replicate his depth, I will channel my “inner-Ahlstrom” to highlight a few of the pieces from my personal notes and memory bank.

Samuel Clement, through Mark Twain, dubs Huck as “the juvenile pariah of the village,” and describes him as “idle, and lawless, and vulgar, and bad,” qualities for which his friends in the village admire him. But Twain admits that the mothers of Huck’s friends “cordially hated and dreaded” him.

Raft on the Mississippi River near Hannibal, MO

In the first chapter of the novel, Widow Douglas adopts Huck Finn and takes him into her home. She is a strict, old guardian who treats Huck as her son, believing that she can educate and “sivilize” him. She whacks him on the head with her thimble, frequently scolding his behavior, and preaches to him from the Holy Bible. She does allow him to use snuff, because she is partial to it herself as well; however, smoking, drinking and cursing are strictly off limits.

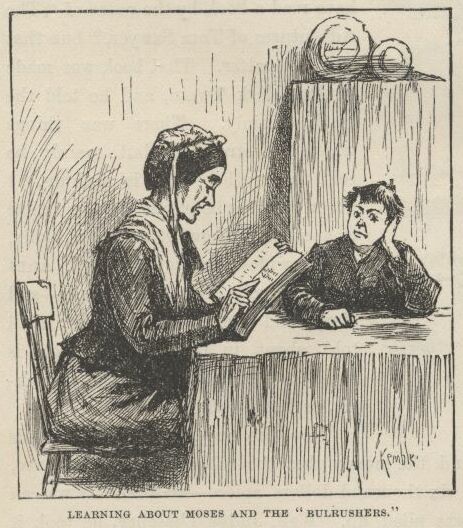

Illustration by E.W. Kemble from the first edition of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn [4]

Widow Douglas most wants to instill in Huck a fear of God. One telling passage is when she reads to Huck from the Good Book [Exodus 2:1-10] about the prophet, Moses:

After supper she got out her book and learned me about Moses and the Bulrushers,

and I was in a sweat to find out all about him;

but by and by she let it out that Moses had been dead a considerable long time;

so then I didn’t care no more about him, because I don’t take no stock in dead people. [5]

Despite his protestations about not taking stock in dead people, Huck’s life as told through his journey with Jim, becomes the story of “Moses and the Bulrushers.” The Bible story is a powerful metaphor of adventure and self-discovery. The Widow Douglas serves as moderator as she reads a prophesy about her soon to be lost adopted child.

The parallels between the life of Moses and the journey of Huck are striking:

- Moses as an infant floats in the Nile River; Huck floats as a child down the Mississippi.

- The wife of the Pharaoh discovers Moses in the bulrushes and raises him as one of her own; Slave Jim raises Huck on the river journey and Huck is born to a new life with his guardian.

- Moses is a messanger from God; Huck is redeemed for his efforts when he returns to St. Petersburg.

- Moses leads his people out of bondage in Egypt to the edge of the Promised Land; Huck helps Jim escape from slavery, and with the help of Tom Sawyer’s Aunt Polly, leads him to the state border, the edge of a new life as a free man.

- Moses becomes an outcast and dies before he can enter into the new Israel; Huck is a pariah among his villagers and leaves the state of Missouri for Indian Country.

The Widow’s Bible reading is a prophesy that comes to life on the river.

Most of the tale follows Twain’s two misfit escapees (slave, Jim, and vagabond, Huck) through a humid gauntlet of adventure. Jim does not have a last name. No known family. Yet he possesses the power of skills, instincts, love, courage and fortitude that his white owners lack.

Jim and Huck flee their island hideout on a raft, when the authorities discover that Huck has faked his own death and Jim has run off to avoid being sold to another slaveholder. The fantastic story flows from the “legal” escape from an abusive father and the “illegal” escape from slavery. The duo hide during the day and run the Mississippi River by night. Along the way they run into every sort of rogue, rascal and grifter a young boy could imagine. Jim can sense evil in other men’s hearts and he uses his instincts. He is truly a trustworthy guardian.

Image of a boat similar to Jim and Huck’s [6]

Huck, despite missing any formal education from school, is an archetypal innocent boy. He picks up enough spelling and reading from Widow Douglas’ sister, Miss Watson, to get by. Huck thinks about right and wrong. He may not have attended Sunday school either, but he keenly discovers the “right thing to do” despite the corporal punishment and Bible thumping around him. He is an independent thinker, especially around slave ownership, which was the prejudiced right of the whites in the South at that era. Twain does not moralize about the topic, yet the character Jim is a powerful reminder of the basic human rights for all people in the Utopian America. One example of young Huck’s moral compass is his decision to help Jim escape slavery, even though Huck believes he is condemning himself to go to hell for it.

Another interesting female character in the novel is Tom Sawyer’s Aunt Polly. She calls Huck Finn a “poor motherless thing.” In the prequel story to Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Huck confesses to Tom that he didn’t feel motherless. He remembers his mother distinctly. But mostly he remembers his alcoholic Pap. His father yelled at his Mom a lot and his parents were relentlessly fighting. The fights only stopped with her death. Justifiably, he feels that he raised himself without the comfort and support of a mother and the example of a good father for many years.

Image of Jim and Huck on the river [7]

The maternal Aunt Polly is a loving woman, but she too often shows her affection by being stern with and condescending of Tom Sawyer. In one episode Aunt Polly receives a letter from her sister, Sally Phelps, stating that Tom’s younger brother, Sid, had arrived safely with Tom at the Phelps’s house. Knowing that Sid was at home with her, Aunt Polly became suspicious. She wrote Sally two letters asking her to explain what she meant by Sid arriving with Tom. When Aunt Polly received no written response, she traveled to the Phelps plantation to find out the truth. Aunt Polly smugly uncovered Tom’s tricks: Huck was hiding out with the Phelps family, as Tom, and Tom was playing Sid. Huck describes Aunt Polly as “looking as sweet and contented as an angel half-full of pie,” when she uncovered the ruse.

A key reason to include Aunt Polly in the story is that she helped secure Jim from a sure return to slavery. She was able to confirm, as a valid witness, that Jim, the former slave being held at the Phelps plantation, was actually a legally free man. Without Aunt Polly’s positive identification, no one would have believed Tom, who had proven himself untrustworthy. Her confirmation prevented Jim from being sold to a new slave owner and headed back into servitude.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art [8]

In the novel, Huckleberry Finn the maternal relationships with Miss Watson, Mrs. Phelps, Widow Douglas, and Aunt Polly are plainly overshadowed by Jim’s influence on Huck’s life. It was their time together on the river that becomes the most enduring and powerful on his young life. Life on the river steers Hugh with firm control. Jim senses the wickedness of other men and women and he protects the young man from their treachery. He comes up with the plan to navigate the rivers, and to land in free territory, when they hit the Ohio. Unfortunately, a fog bank descends on the river and the two miss the mouth of the Ohio River and the float to freedom. Instead they return to St. Petersburg, only to discover that the corpse in their island hideout is Huck’s father, Pap Finn. Jim risked his freedom for Huck; what an act of love he showed his young accomplice!

The metaphor of the Nile and the Mississippi is a show stopper. The name Moses means “a stranger among us” which is exactly what Huck felt he was in his hometown. Both Moses and Huck were perpetrators of civil disobedience. Both were deeply flawed individuals, conflicted about their identities, ophaned and homeless for long stretches of their lives. They were criminals in their home towns. And the stories of redemption are throughout: the lives of both of these men were dramatically changed and repurposed for the greater community.

The lyrics of the Huck and Jim story, as read to the class by Professor Ahlstrom, still sound as melodic and urgent to my ears as they did back in the day. Trips downriver and upriver, trips across the ocean, all metaphorical trips can be transformative. As Mark Twain predicts:

Twenty years from now,

you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the ones you did do.

So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails.

Explore. Dream. Discover. [9]

References:

[1] http://gallery4collectors.com/AndyThomas-HuckleberryFinn.htm

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sydney_E._Ahlstrom

[3] https://thewayofimprovement.com/category/sydney-ahlstrom/

[4] Clement, Samuel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Random House, 1885.

[5] Ibid, page 4.

[6] http://aaabadieenglish10.weebly.com/huck-finn.html

[7] http://2readornot2read.weebly.com/the-adventures-of-huckleberry-finn-pacing-guide.html

[8] http://www.reynoldahouse.org/

[9] http://www.twainquotes.com/quotesatoz.html