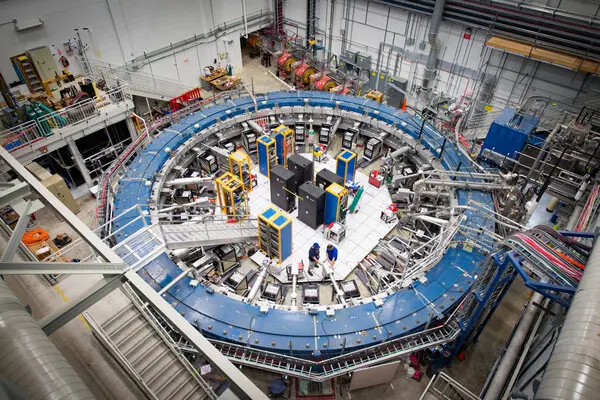

The Muon g-2 Ring at Fermilab particle accelerator complex in Batavia, Ill. Photo Credit…Reidar Hahn/ Fermilab, via US Dept Of Energy

Word Smith: Muon

It seems like it happened in an instant, however, this was an announcement that had been years in the making. The US and international physicists have recommended a pause into further research on particles such as Electrons, Protons, Quarks and Higgs Boson. Instead they urge that future grants shift funding to subatomic particles known as Muons. Although electron and protons are still important in the physics world, now all the buzz is around muons. What exactly is a muon? And what about its “deviant movements” makes it worth billions of dollars for future research? Those are the question for this Word Smith post.

Exploring the Quantum Universe

Physicists claim that their research projects, ”Exploring the Quantum Universe: Pathways to Innovation and Discovery in Particle Physics,” are critical because they open a portal to a new physics of our universe. According to Katrina Miller, a New York Times science reporter who recently earned a Ph.D. in particle physics, researchers convened this past August in Liverpool, England, to unveil a single number related to the behavior of the muon.[1]

There was a collective exhale across multiple continents when scientists claimed they discovered that the muon behaved exactly the way they had computed it would behave two years earlier, but now with greater precision. The precision, found through experiments at the Fermi National Accelerator Lab in Batavia, Illinois, relates to a movement of the muon, known as the Muon g-2 Collaboration.

“It really all comes down to that single number,” said Hannah Binney, a physicist at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory who worked on the muon measurement as a graduate student. Scientists are putting to the test the Standard Model, a grand theory that encompasses all of nature’s known particles and forces. Although the Standard Model has successfully predicted the outcome of countless experiments, physicists have long had a hunch that its framework is incomplete. The theory fails to account for gravity, and it also can’t explain dark matter (the glue holding our universe together), or dark energy (the force that is pulling it apart).

So What is a Muon?

One of many ways that researchers are looking for physics beyond the Standard Model is by studying muons. Referred to as “the heavier cousins of the electron,” muons are unstable subatomic particles, which survive just two-millionth’s of a second before decaying into lighter particles. They also act like tiny bar magnets: Place a muon in a magnetic field, and it will wobble around like a top. The speed of that motion depends on a property of the muon called the magnetic moment, which physicists abbreviate as g.

In theory, g should exactly equal 2. But physicists know that this value gets ruffled by the “quantum foam” of virtual particles that blip in and out of existence and prevent empty space from being truly empty. These transient particles change the rate of the muon’s wobble. By taking stock of all the forces and particles in the Standard Model, physicists can predict how much g will be offset. They call this deviation g-2.

But if there are unknown particles at play, experimental measurements of g will not match this prediction. “And that’s what makes the muon so exciting to study,” Dr. Binney said. “It’s sensitive to all of the particles that exist, even the ones that we don’t know about yet.” Any difference between theory and experiment, she added, means new physics is on the horizon.

What is the g-2 wobble?

To measure g-2, researchers at Fermilab generated a beam of muons and steered the beam into a 50-foot-diameter, doughnut-shaped magnet, the inside brimming with virtual particles that were popping into reality. As the muons raced around the ring, detectors along its edge recorded how fast they were wobbling. Using 40 billion muons — five times as much data as the researchers had in 2021 — the team measured g-2 to be 0.00233184110, a one-tenth of 1 percent deviation from 2. The result has a precision of 0.2 parts per million. That’s like measuring the distance between New York City and Chicago with an uncertainty of only 10 inches, one researcher estimated.

But whether the measured g-2 matches the Standard Model’s prediction has yet to be determined. That’s because theoretical physicists have two methods of computing g-2, based on different ways of accounting for the strong force, which binds together protons and neutrons inside a nucleus.

The traditional calculation relies on 40 years of strong-force measurements taken by experiments around the world. But with this approach, the g-2 prediction is only as good as the data that are used, said Aida El-Khadra, a theoretical physicist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a chair of the Muon g-2 Theory Initiative. Experimental limitations in that data, she said, can make this prediction less precise.

How Should Physicists Measure a Muon?

A newer technique called a lattice calculation, which uses supercomputers to model the universe as a four-dimensional grid of space-time points, has also emerged. This method does not make use of data at all, Dr. El-Khadra said. There’s just one problem: It generates a g-2 prediction that differs from the traditional approach. “No one knows why these two are different,” Dr. Alex Keshavarzi said. “They should be exactly the same.”

Rarely in physics does an experiment surpass the theory, but this is one of those times, Dr. Kevin Pitts said. “The attention is on the theoretical community,” he added. “The limelight is now on them.”

Dr. Binney said, “We are on the edge of our seats to see how this theory discussion pans out.” Physicists expect to better understand the g-2 prediction by 2025. Gordan Krnjaic, a theoretical particle physicist at Fermilab, noted that if the experimental disagreement with theory persisted, it would be “the first smoking-gun laboratory evidence of new physics,” he said. “And it might well be the first time that we’ve broken the Standard Model.”

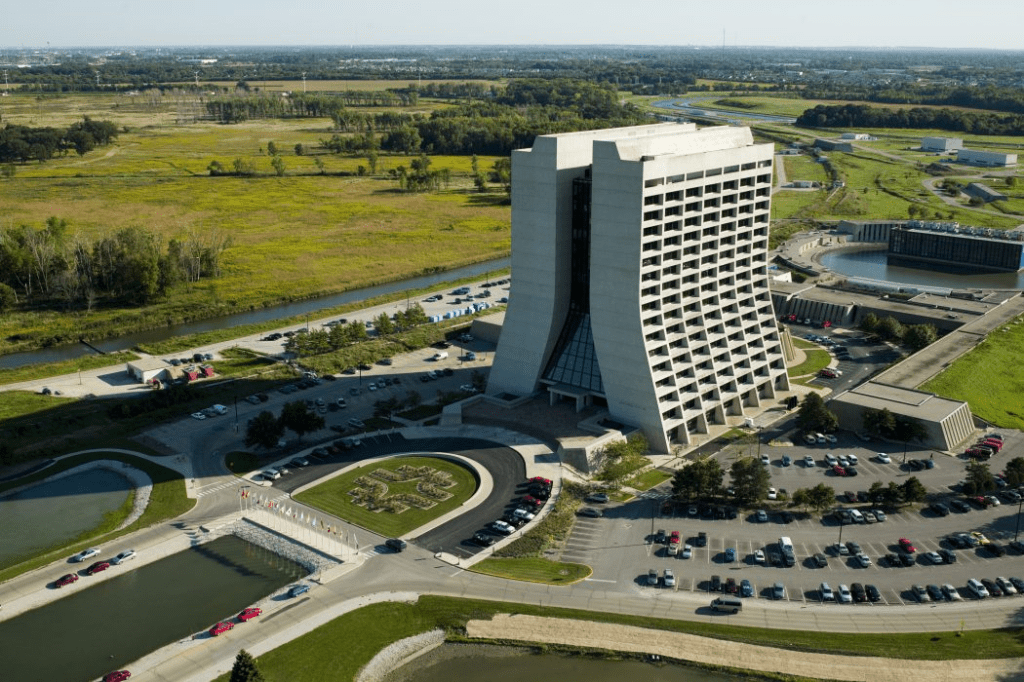

Fermilab, Batavia, Illinois, US Dept of Energy

While the two camps of theory hash it out, experimentalists will hone their g-2 measurement further. They have more than double the amount of data left to sift through, and once that’s included, their precision will improve by another factor of two. “The future is very bright,” said Graziano Venanzoni, a physicist at the University of Liverpool and one leader of the Muon g-2 experiment, at a public news briefing about the results.[2]

The latest result moves physicists one step closer to a Standard Model showdown. But even if new physics is confirmed to be out there, more work will be needed to figure out what that actually is. The discovery that the known laws of nature are incomplete would lay the foundation for a new generation of experiments, Dr. Alex Keshavarzi said, because it would tell physicists where to look. “Physicists get really excited when theory and experiment do not agree with each other,” said Elena Pinetti, a theoretical physicist at Fermilab who was not involved in the muon g-2 work. “That’s when we really can learn something new.”

For Dr. Kevin Pitts, who has spent nearly 30 years pushing the bounds of the Standard Model, proof of new physics would be both a celebratory milestone and a reminder of all that is left to do. “On one hand it’s going to be, ‘Have a toast and celebrate a success,’ a real breakthrough,” he said. “But then it’s going to be ‘back to work.’ What are the next ideas that we can get to work on?”

References:

[1] There have been several stories in the New York Times, science sections on muons lately. This is one from this summer in mid August: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/10/science/physics-muons-g2-fermilab.html