Word Smith: Hyperaccumulators

The New Weapon Against China’s Mineral Dominance: Plants

The search for new suppliers for the minerals needed for everything from batteries to missiles has driven novel extraction methods

Om Parkash Dhankher’s project grows plants that can absorb and store metals extracted from soil

By Jon Emont | Photographs by Sophie Park for WSJ

Updated Jan. 25, 2025 at 12:01 am ET

AMHERST, Mass.—Money doesn’t grow on trees. But soon the minerals used in the battery of your electric vehicle might.

Worries about China’s domination of critical minerals are driving Western scientists and companies to embark on increasingly novel ways to develop alternative sources.

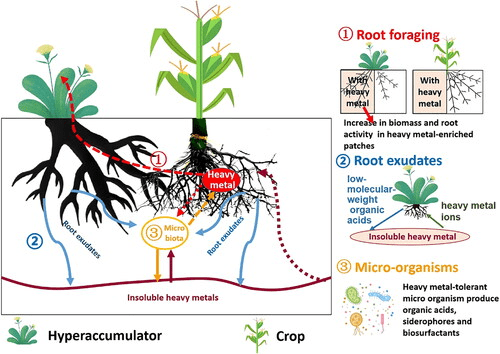

One such effort seeks to exploit a quirk of nature: Certain plants, called hyperaccumulators, absorb large quantities of minerals, like nickel and zinc, from the soil. Cultivating these plants, and then incinerating them for their metal, could provide U.S. companies with a small stream of domestically sourced minerals—without the expense and environmental destructiveness of conventional mining.

“When we’re in this intense competition we do have to think about alternative methods,” said Evelyn Wang, the former director of ARPA-E, an Energy Department agency that is dispensing $10 million to find ways to make nickel farming feasible in the U.S. “It is a technological white space that potentially could be transformative.”

At a greenhouse in Amherst, professors are using the funding to undertake gene editing to build a new fast-growing, nickel-absorbing oilseed plant. If successful, the plant could be used to harvest the metal from mineral-rich soils in states such as Maryland and Oregon.

Meanwhile, an American startup called Metalplant is paying a dozen farmers in Albania to farm nickel using a local plant species. The company is editing the genes of those plants to adapt them to the U.S.

Nickel extraction from plants

Nickel is the element of choice in this experiment.

STEP 1 Plant roots absorb nickel from the soil.

STEP 2 Nickel is transported to the shoots.

STEP 3 Plants are dried and incinerated, becoming an ashy nickel concentrate.

STEP 4 This concentrate can be further purified and turned into battery–grade material.

Sources: Metalplant; Om Parkash Dhankher; WSJ reporting, Ming Li/WSJ

“This could shift how we think about mining in the future,” said Eric Matzner, the company’s chief executive.

Some 10 million acres of barren, nickel-rich soil are scattered around the U.S. In such areas, concentrations of minerals are generally too low to justify large-scale mining, but could offer opportunity for inexpensive nickel farming.

In the case of nickel phytomining, as such efforts are known, the plants are dried and incinerated, leaving an ashy nickel concentrate. This concentrate can then be further purified and turned into battery-grade material.

To be sure, phytomining is small in scale. Companies in the field are targeting harvests of around 300 pounds of nickel per acre per year, roughly enough for six EV batteries.

But the funding for nickel-farming plants is one small piece of a broad effort by the U.S. government to develop secure supplies of the minerals that are needed for defense and cutting-edge industry, and are an area where China is dominant.

In recent years, Chinese mining and processing companies have won a near-monopoly on minerals used in batteries, lasers and bombs, in part because of those companies’ lower costs and superior processing technology.

Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst are hoping mineral-rich soil can be used to grow plants for the harvesting of metals such as nickel.

Many Western attempts to fight back have fizzled. The heavy costs and environmental regulations involved in setting up mines in rich countries have frustrated American miners. The U.S. currently has only one operating nickel mine, the Eagle mine in northern Michigan, but that is slated to shut in 2029.

In recent years, nickel mines in Brazil, New Caledonia and Australia have closed, unable to compete with low-cost Chinese refiners. Today, Chinese companies control around 54% of the global supply of refined nickel, up from 34% in 2015, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. Its companies control an even higher share of key technology minerals such as lithium, cobalt and rare earths.

China has recently flexed its muscles by restricting exports to the U.S. of strategic minerals such as antimony and gallium, which are used in semiconductors and weaponry. Beijing may use the tactic again in response to the new tariffs on Chinese goods floated by President Trump.

In response, the U.S. is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on conventional efforts such as drilling for underground mineral deposits and building domestic refining facilities. But environmental reviews have slowed some efforts, while domestic miners face higher production costs than Chinese rivals, scaring off investors.

In search of alternative sources of metals, government agencies are funding ideas once regarded as outlandish.

In 2023, ARPA-E dispensed $5 million to explore extracting minerals like rare-earth elements—which are crucial to radar and missile systems—from seaweed. Another program from the defense department seeks to design microbes to separate rare-earth elements from ore.

Rufus Chaney, an agronomist who many consider to be the father of phytomining, struck on an idea when he was working on decontaminating soil in the 1980s. Could he use hyperaccumulating plants to both remove nickel from mine sites, and then harvest it from plants afterward?

“You’re cleaning up the soil while making a profit selling the nickel,” said Chaney, who spent decades conducting research on cleaning contaminated soils for the U.S. Agriculture Department.

If Dhankher succeeds, farmers planting his creation in nickel-rich soils in the U.S. could glean revenue both from seed oil and minerals.

However, when Chaney worked with a mining company to clean up soil near a mine site in Canada, he found that the plant roots stretched deeper than the contaminated soil’s top layers so failed to absorb the nickel deposits. Chaney concluded that phytomining should be used where nickel naturally is found deep in the soil.

A private company piggybacked off Chaney’s research to attempt to phytomine nickel, but by 2009 the plant had become invasive, spreading beyond the planted fields and outcompeting native flora. Authorities in Oregon declared the plant, known as Alyssum, a noxious weed and instructed anyone who encountered it to dial the state’s intruder species hotline, “1-866-invader.”

Brett Robinson, a professor at New Zealand’s University of Canterbury, is a co-author of a decade-old paper “Phytoextraction: Where’s the Action?” That paper concluded that phytomining was inefficient, in part because of the expense involved in gathering the ore from scattered farms and delivering it to nickel smelters.

“I was frankly surprised at the renewed interest,” he said of the U.S. government’s new program.

Now, a handful of private companies are seeking to capitalize on the appetite for minerals that are both environmentally sustainable and free of Chinese influence.

The nickel recovered from plants is already in a purer chemical form than that coming from conventional mining, saving on energy-intensive and costly processing.

One phytomining initiative is Botanickel, a tie-up between Econick, a biotechnology company, and Aperam, a Luxembourg-headquartered steel company on the hunt for environmentally friendly nickel.

Botanickel has greenhouses in Europe and Malaysia, where it grows a nickel-absorbing plant that has been named Phyllanthus Rufuschaneyi—after Chaney, who advises the company. The company is hoping to commercialize production as soon as possible.

A student in Dhankher’s lab processes a dried sample of camelina exposed to nickel in a mixer mill.

A team led by Om Parkash Dhankher, a plant biotechnologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, recently received $1.3 million in U.S. funding to try to imbue an oilseed plant with genetic material from the nickel-absorbing plant deemed a noxious weed by Oregon authorities.

Dhankher’s team must isolate the array of genes involved in absorbing nickel and then shift them into an entirely new plant. Nickel is toxic to plants, so consuming the nickel could kill the oilseed plant. As a result, Dhankher’s team must identify the genes that will direct the nickel flow to central vacuoles—parts of plant cells that function as landfills—where the nickel can be stored safely.

By taking the nickel-absorbing genes from Alyssum and inserting them into the oilseed plant, which is widely cultivated in North America, they hope to avoid it becoming the noxious type that prompted pushback from state authorities.

If Dhankher succeeds, farmers planting his creation in the nickel-rich soils of Oregon or Maryland could glean revenue both from seed oil, used in biofuel, and nickel.

On a recent day, the lab and greenhouse saw a flurry of activity. A postdoctoral researcher ground a plant that has been exposed to nickel to extract its RNA so that the team can work out how exposure to nickel alters its genes.

“Our target is to have maximum accumulation,” Dhankher said.

Om Parkash Dhankher looks at plant samples at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Write to Jon Emont at jonathan.emont@wsj.com