Shubhendu Sharma’s Backyard Forest in 2016

Word Smith: Miyawaki Method

Known in various parts of the world as tiny forests, pocket forests, and in the United Kingdom as “wee” forests, there is a movement afoot in the forest environment. It is to create Miyawaki Forests. Named after the Japanese botanist and plant ecologist, Dr. Akira Miyawaki, the “method” or movement has gained traction on every continent, save Antarctica, as one of the best ways to create fast-growing native forests.

Miyamaki developed his techniques in the 1970’s, after observing that thickets of indigenous trees and shrubs around Japan temples and shrines were healthier and more resilient than those in single-crop plantations or forests. The single crop forests rarely protected the old-growth forests and were highly susceptible to deforestation, fire and diseases. There are several key advantages to the Miyawaki Method: native species of plants provide vital resilience amid climate change and the community has excellent access to nature in their neighborhoods.

Unfortunately for the rest of us, Dr. Miyawaki died in 2021 at the age of 93. In 2006 he won the Blue Planet Prize, which is widely considered the Nobel award for ecology.

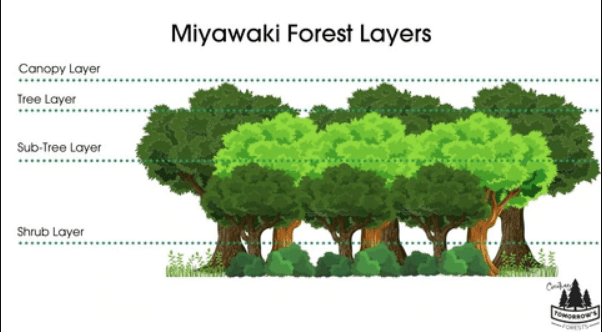

One of the most noticeable differences in a Miyawaki forest is that the seedlings are planted at very high densities. The theory is that this replicates the regeneration process that occurs in a natural forest when a clearing in the canopy opens up due to a larger tree falling. The saplings grow very fast to compete for the light and then natural selection will favor the fastest growing individuals and act to thin out the trees. The result is a densely packed pioneer forest that grows in 20 to 30 years instead of taking 150 to 200 years. This has obvious benefits for projects that are working to maximize a forest’s carbon sequestration potential or recreate habitat for biodiversity and wildlife.

Dr. Akira Miyawaki (1928-2021)

Not everyone believes in this method of forestry, but it is gaining traction in many urban areas, where carbon sequestration is prized and valued by businesses, which are seeking carbon credits. The Miyawaki Method is not all a bed of roses, as it has its own critics.

The planting method has been criticized for creating forests that look monotonous, because the trees are all the same age. The foresters counter that the diversity inherent in the planting and the biodiversity, which has been recorded is prolific: more than 3000 sites have been identified world-wide. These sites demonstrate that a functioning ecosystem has been created, and that the appearance of the forests is more of an aesthetic issue.

It is important to note, as critics have also stated, that the Miyawaki Method is a more expensive method of planting, because it requires soil enhancements and more seedlings to cover a certain area; however, the rapidity of the forest growth and the minimal maintenance required recompense some of that initial expenditure. One forest in Cambridge, MA cost $18,000 for the plants and extensive soil treatment, not including the consulting fees and labor. For comparison the cost of a single street tree in Cambridge is about $1,800 in 2023 dollars.

The Miyawaki Method received some unexpected popularity, when in 2014, an Indian engineer, named Shubhendu Sharma took part in the plantings in his native India. Sharma was so enthralled that he turned his own backyard into a forest and he created a plant company called Afforestt. Then Sharma was inspired to create a 2016 TED Talk entitled How to Grow a Forest in Your Backyard, about the Miyawaki Method. The TED Talk attracted over 3.7 million viewers as the story went viral. [2]

The devout followers of the Miyawaki Method believe that it is an effective way of jump starting the creation of a forest or woodland, with considerable benefits for carbon capture and recreating biodiversity. At one organization, Creating Tomorrow’s Forests, they consistently employ the Miyawaki Method alongside restoration of other habitats such as ponds and meadows, to create diverse, rich forest ecosystems for people and wildlife.

It may be time for every neighborhood to pull up the English Ivy, pickleball court, or grass and start planting our own forests of the future. Miyawaki has shown us the way.

[1] https://www.creatingtomorrowsforests.co.uk/blog/the-miyawaki-method-for-creating-forests

[2] https://www.ted.com/talks/shubhendu_sharma_how_to_grow_a_forest_in_your_backyard?language=en