Witness Post: Pointe du Hoc

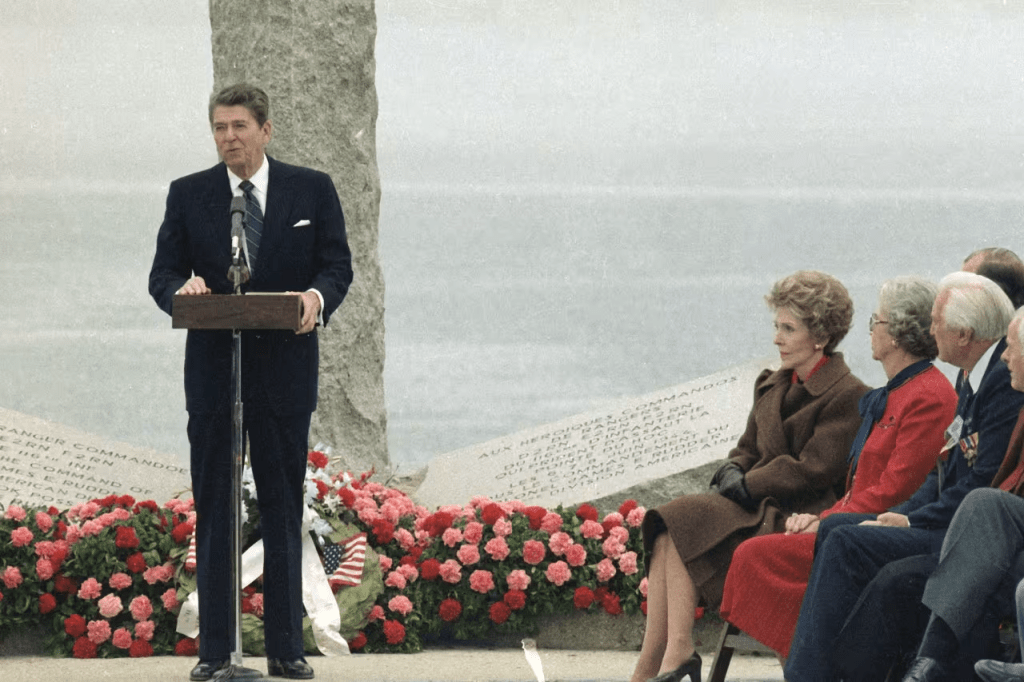

In June 1984, forty years after the start of D-Day on the northern coast of France, Pres. Ronald Reagan gave a speech that stirred the hearts and minds of Americans and French citizens alike. The world was paralyzed by the Cold War and it was a dangerous time for all NATO countries and for Russia.

As I read an OpEd article by Peggy Noonan in the Wall Street Journal on June 8, 2024, [1] my mind wandered to the stories told by my grandfather, Gen. Henry C. Evans. He was with Gen. George Patton in Italy and North Africa at the time of D-Day. The allied forces were fighting against German armies of Field Marshal Rommel, known as the “Desert Fox.” Rommel seemed to be everywhere: leading the Afrika Korps in North Africa and overseeing the fortification of the bunkers and German defences in northern France. Evans missed the in-person carnage of the D-Day invasion, so he had only oral and written accounts of the day from General Eisenhower and other survivors. Decades later, Evan was selected as an Army advisor on the movie, Patton, starring George C. Scott. On the whole, Gen. Evans said the director, “Got it about right…describing Patton as the historian, the fighter, the commander.”

The recollections of Ms. Noonan of President Reagon’s speech are powerful. They brought me to tears, as did our family trip to Normandy a few years ago. Lest we forget, 50,000 people gave their lives over those days to take back Europe for its citizens.

Below are excerpts of the Noonan WSJ article along with some photos of Pointe du Hoc from our family trip with Tracy and Margaret.

President Reagan delivers speech commemorating the 40th anniversary of D-Day in Normandy, France, June 6, 1984. PHOTO: ASSOCIATED PRESS

Ronald Reagan was the last unambiguously successful American president. In January 1981, he walked into his presidency saying he would do two big and unlikely things, one domestic and one in foreign affairs, and walked out in January 1989 having done them. He revitalized the U.S. economy after decades of drift and demoralization, and he defeated the Soviet Union, the Berlin Wall falling months after he left the presidency. He did a third thing he hadn’t promised. He changed the mood of the country. We’d been depressed since JFK’s assassination and Vietnam, since Nixon and Watergate. Reagan said no, we aren’t a spent force, we aren’t incapable, we’ve got all this energy and brains. We’ve got this, he said. We did.

When presidencies are huge they are clear and you don’t have to finagle around with vague or technical language to cite their achievements.

To the D-Day speech at Pointe du Hoc. There’s something I always want to say about it.

The speech was a plain-faced one. It was about what it was about, the valor shown 40 years before by the young men of Operation Overlord who, by taking the Normandy beaches, seized back the Continent of Europe.

But there was a speech within the speech, and that had to do with more-current struggles.

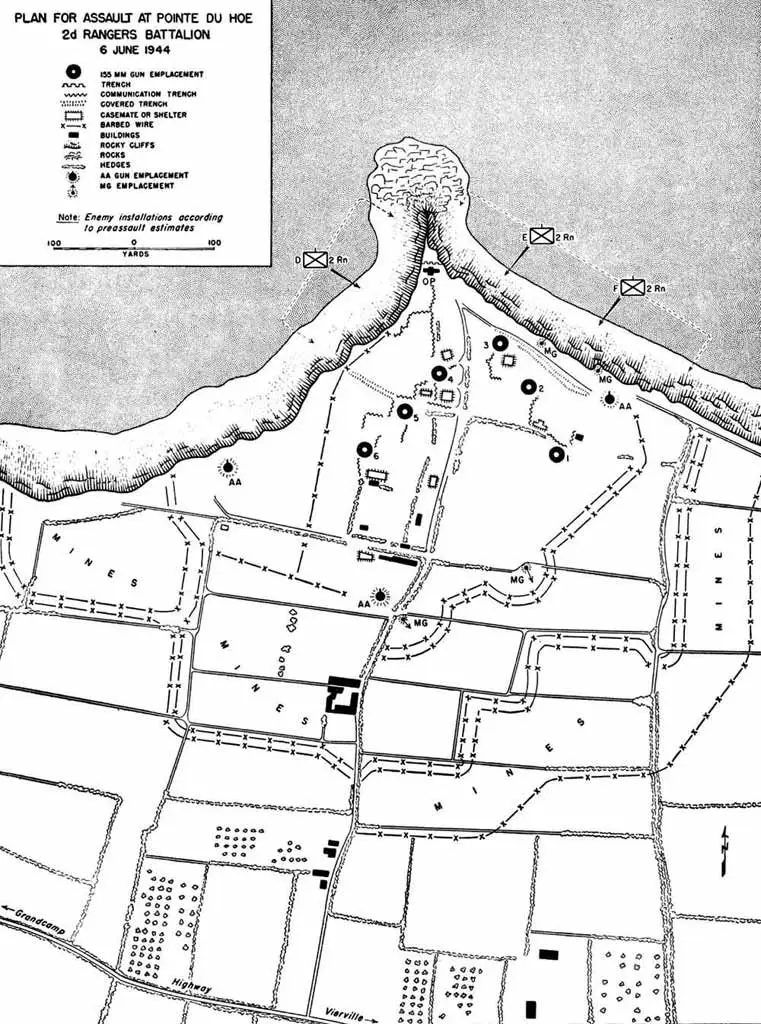

Reagan wished to laud the reunited U.S. Rangers before him, so he simply described what they’d done: “At dawn, on the morning of the 6th of June, 1944, 225 Rangers jumped off the British landing craft and ran to the bottom of these cliffs.” Their mission was one of the hardest of the invasion, to climb the cliffs to take out enemy guns.

“And the American Rangers began to climb.” They shot rope ladders, pulled themselves up. “When one Ranger fell, another would take his place.” Two hundred twenty five Rangers had come there. “After two days of fighting, only 90 could still bear arms.”

“Behind me is a memorial that symbolizes the Ranger daggers that were thrust into the top of these cliffs. And before me are the men who put them there. These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs.”

The “boys,” in the front rows, began to weep. They had never in 40 years been spoken of in that way, their achievement described by an American president, who told all the world what they’d done. Nancy Reagan and others, as they looked at them, were moved, and their eyes filled. Reagan couldn’t show what he was feeling, he had to continue. But afterward, in the Oval Office, he told me of an old Ranger who, before the ceremony, saw some young U.S. Rangers re-enacting the climb, and the old vet joined in and made it to the top. Reagan’s eyes shined: “Boy, that was something.”

The speech within the speech was about the crisis going on as Reagan spoke. The Western alliance was falling apart. Its political leaders were under severe pressure at home. British, West German and Italian peace movements had risen and gained influence in 1982 and 1983, pushing to stop the U.S.-Soviet arms race. The Soviets had placed SS-20 missiles in Eastern Europe. In response, in late 1983, the U.S. put Pershing II and cruise missiles in Western Europe. Arms talks continued but went nowhere, and the Soviets often walked out. In New York, a million antinuclear protesters had marched from Central Park to the United Nations. In Bonn, hundreds of thousands protesters took to the streets in what police called the largest demonstration since the end of the war.

It was one of the tensest moments of the Cold War.

Reagan hated nuclear weapons but believed progress couldn’t be wrung from the Russians with words and pleas. More was needed, a show of determination.

He understood the pressure the political leaders of the West were under, and at Pointe du Hoc he was telling them, between the lines: Hold firm and we will succeed.

That’s why he spoke at such length of all the Allied armies at D-Day, not only the Americans. It’s why he paid tribute to those armies’ valor—to remind current leaders what their ancestors had done. It’s why he talked about “the unity of the Allies.” “They rebuilt a new Europe together.”

He was saying: I know the pressure you’re under for backing me, but hold on. They pretty much did. And in the end the decisions of 1983 and ’84 led to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, signed in 1987 by Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, a turning point in the Cold War.

If you hear that speech, be moved by the Rangers who climbed those cliffs and the country that sent them there. Care that Ronald Reagan became the first public person to capture and laud the greatest generation, but delicately, because it was his generation and he couldn’t self-valorize. (Yes, a sweeter time.) But he was telling the young: That guy you call grandpa, see him in a new way. See his whole generation for who they were.

And hear, too, a message that echoes down the generations: Good people with a great cause must stand together, grab that rope and climb, no matter what fire.

A Memorial Plaque to the Rangers who gave their lives to scale the cliffs to Pointe du Hoc.

One of the remaining cement encased cannon locations on the top of the Pointe du Hoc

Another cannon location on Pointe du Hoc, Normandy

Photos and descriptions of the scaling of Pointe du Hoc in Normandy

The view of the Normandy coast, seen through barbed wire left in place on the hilltop

[1] https://www.wsj.com/articles/reagan-at-pointe-du-hoc-40-years-later-f0c5a7f9