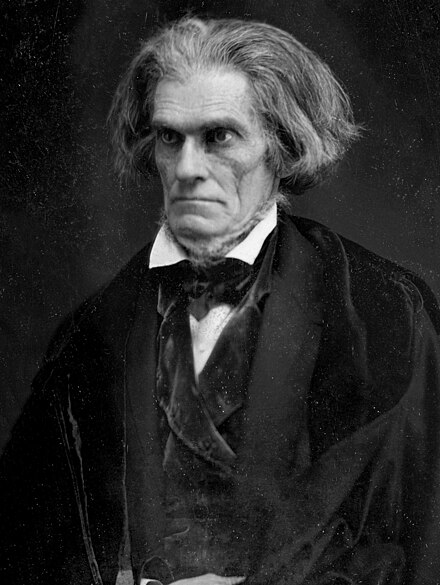

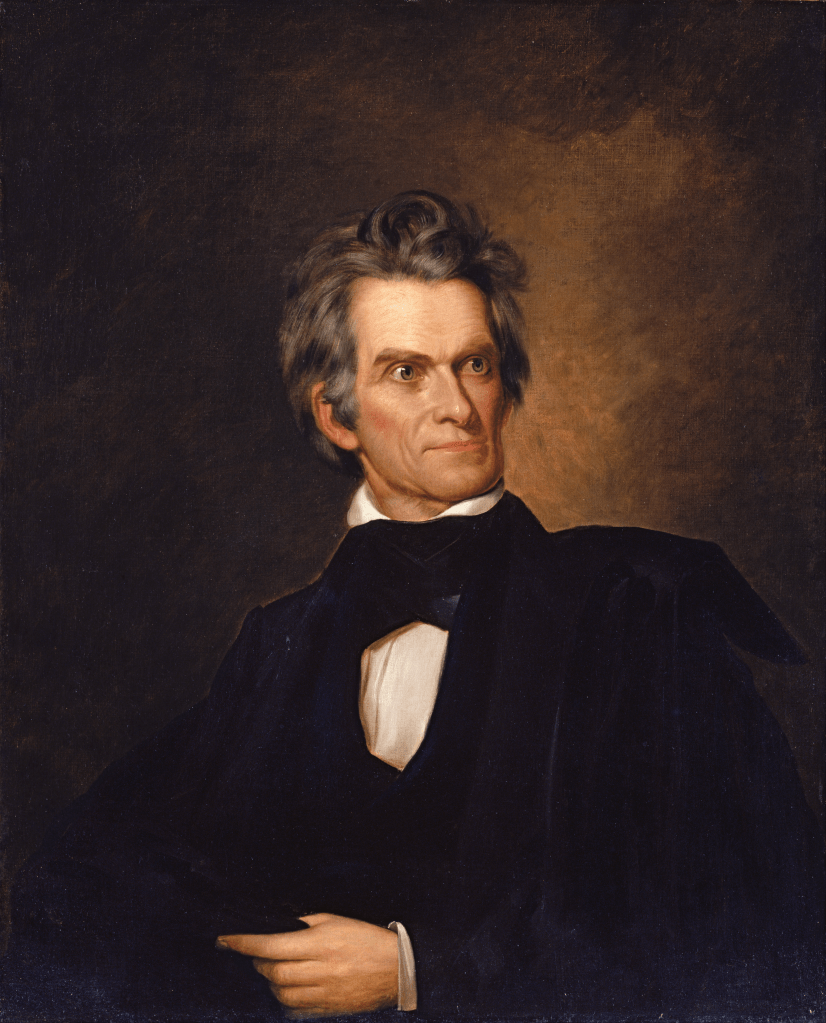

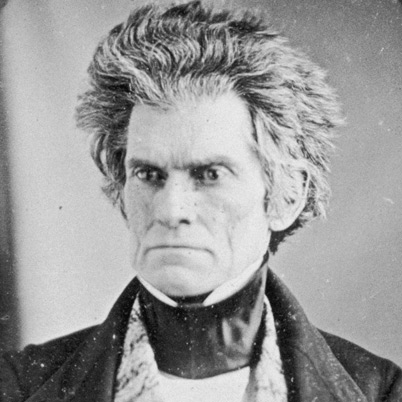

John C. Calhoun (1782 – 1850) Yale B.A. 1804, Yale LL.D. 1822

Witness Post: John C. Calhoun

”Change the name!” The crowd shouted at the administrator. “Calhoun was a slave owning bastard and a rotten-to-the core politician!” The hecklers were not students, but agitators. “CHANGE-THE-NAME,” they chanted.

Referring to John C. Calhoun, the crowd’s jeers didn’t necessarily square with the feelings that the alumni of the college felt. Nor did the chants land well with the students, when thinking about their college dorms, their suite mates, or the overseers at Calhoun College (one of the undergraduate residence halls at Yale). Strong bonds with their classmates meant the world to these students. The name of the college was not the main consideration for them here: their fellow students and classmates were front and center. And the Yale undergraduate alumni who were in Calhoun had a deep seated Calhoun-pride that rose above historical politics and ancient racial squabbles. The alums lamented over protests.

However, as months dragged on, it seemed as if the name change for the residential college, mired in rancor and controversy, was inevitable.

Who Was This Man? Why Is Everyone So Angry With Yale?

John Caldwell Calhoun was an American statesman and political theorist, who served as the seventh vice-president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He also served as a Senator, Secretary of State, and Secretary of War under various administrations. He was appointed to positions as a Republican, a Democrat, and as a Whig, artfully finding and then opportunistically aligning himself with the party that served him best.[1]

After reviewing his life, it will be important to recall “what he stood for and did” with his political positions of power for the benefit of all constituents.

Calhoun Beginnings

Born in South Carolina, John Calhoun was the fourth child of Patrick Calhoun and Martha Caldwell. The elder Calhoun and his wife were both Irish immigrants who sailed to the States from Ulster and County Donegal. They landed in Charleston and settled, raising a family in the low country of South Carolina. With the financial support of his older brothers, John Calhoun attended and graduated from Yale College in 1804. He went on to study law at the Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut. [Yale claims Calhoun as a Yale Law School honorary LL.D. grad in 1822.] He was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1807. In 1811 he married Floride Bonneau, who was his first cousin once removed. The couple had 10 children over the next sixteen years. Three of their children died of various ailments in infancy, leaving seven children who survived to adulthood.

Calhoun is described by historians as high-strung. They described him as a brilliant intellectual orator and strong organizer. With a political base among the Irish, Calhoun won his first election to Congress in 1810. In those early years he became a leader of the “War Hawks,” along with House Speaker Henry Clay.

War of 1812

On June 3, 1812, Calhoun’s committee called for a declaration of war against Great Britain. When the War of 1812 was declared, Calhoun labored to raise troops and provide funds to aid the war effort. Disasters on the battlefield lead to the signing of the Treaty of Ghent eighteen months later on Christmas Eve, 1814. The mismanagement of the US Army for most of the war greatly upset Calhoun, and he resolved to strengthen the War Department, so it would never fail again.

In 1817, President James Monroe appointed Calhoun to be Secretary of War, where he served until 1825. Calhoun’s first priority was to create an effective navy, including steam frigates, and a standing army of adequate cavalry size. He also wanted a system of government taxation which would not be subject to collapse by any war-time shrinkage of maritime trade, like customs duties.

Calhoun’s political ambitions, as well as those of William H. Crawford, the Secretary of the Treasury, welled up over pursuit of the presidency in 1824. These political wranglings complicated Calhoun’s tenure as War Secretary. After failing to gain party support to run for president, Calhoun agreed to be a candidate for vice president. The Electoral College elected Calhoun vice president by an overwhelming majority.

Calhoun served as vice-president under both President John Quincy Adams and President Andrew Jackson. Adam’s loss to Jackson in the election of 1828 made Calhoun the most recent U.S. vice president to serve under two different presidents. During his political career, Calhoun adamantly defended the right of American farmers to own slaves, and he sought to protect the financial interests of white Southerners.

Calhoun, in the early years, was described as an ardent nationalist, a moderizer and a proponent of a strong federal government and protective tariffs. By the late 1820s, however, his views had changed radically, as they did at other times in his political career. In lieu of a strong government with steep tariffs, he became a leading proponent of states’ rights, limited federal government, nullification, and opposition to high tariffs. Calhoun saw Northern acceptance of those policies as a condition of the South’s remaining in the Union. His beliefs heavily influenced the South’s secession from the Union for many years after his death (1850). The Southern States finally seceeded from the Union in 1860 and 1861.[1]

Calhoun resigned from his VP post in 1832 to secure a seat in the US Senate; he was the first of two vice presidents to resign from the position, the second being Spiro Ted Agnew, who resigned in 1973.

Political Dynamics at Work

Calhoun had a difficult relationship with Andrew Jackson, primarily because of the Nullification Crisis and what was called “the Petticoat affair.” In contrast with his previous sentiments towards nationalism, Calhoun vigorously supported South Carolina’s right to nullify federal tariff legislation that he believed unfairly favored the North. Calhoun’s states’ rights stance put him into conflict with Unionists such as Jackson. In 1832, with only a few months remaining in his second term, Calhoun resigned as vice president and was elected to the Senate. He sought to be nominated for the presidency by the Democratic Party in 1844 but lost again. This time he lost to surprise nominee James K. Polk, who won the general election. Calhoun went on to serve as Secretary of State under President John Tyler from 1844 to 1845. In that role as Secretary of State he supported the annexation of Texas as a means to extend the Slave Power and helped to settle the Oregon boundary dispute with Britain.

Later in life, Calhoun became known as the “cast-iron man” for his rigid defense of white Southern beliefs and practices. His concept of republicanism emphasized pro-slavery thought and minority states’ rights as embodied by the South. He personally owned dozens of slaves, when he lived in Fort Hill, South Carolina, near Clemson, and he asserted that slavery, rather than being a “necessary evil,” was a “positive good” that benefited both slaves and enslavers. To protect minority rights against majority rule, he called for a concurrent majority by which the minority could block some proposals that it felt infringed on their liberties. To that end, Calhoun supported states’ rights and nullification, through which states could declare null and void all federal laws that they viewed as unconstitutional. Calhoun was one of the “Great Triumvirate” or the “Immortal Trio” of congressional leaders, along with his two colleagues Daniel Webster and Henry Clay.

In the late 1840s Calhoun returned to the Senate, where he opposed the Mexican–American War, the Wilmot Proviso and the Compromise of 1850. He often served as a virtual independent who variously aligned his beliefs as needed with Democrats, Republicans and Whigs.[1]

John Caldwell Calhoun died of tuberculosis at a boarding house in Washington, D.C. in March, 1850. He was 68 years old.

The Calhoun Legacy and Yale

It is interesting to note that the name of Calhoun College had long been a subject of discussion and controversy on the Yale campus. John C. Calhoun leaves behind the legacy of a leading statesman who used his office to advocate ardently for slavery and white supremacy. In 1850, when Benjamin Silliman, Sr. (1796 B.A., 1799 M.A.) learned of Calhoun’s death, he mourned the passing of his contemporary, while immediately condemning his legacy:

“[Calhoun] in a great measure changed the state of opinion and the manner of speaking and writing upon this subject in the South, until we have come to present to the world the mortifying and disgraceful spectacle of a great republic — and the only real republic in the world — standing forth in vindication of slavery, without prospect of, or wish for, its extinction. If the views of Mr. Calhoun, and of those who think with him, are to prevail, slavery is to be sustained on this great continent forever.”

Why should we listen to Silliman? First, he was a distinguished professor of chemistry at Yale. He is also the namesake of another residential college. For the rest of his life, Silliman’s conviction remained that Calhoun was one of the more influential champions of slavery and white supremacy. His bigoted views speak across the generations to people today.

As a national leader, Calhoun helped enshrine his racist views in American governmental policy, transforming them into consequential actions. The Calhoun legacy that Benjamin Silliman decried was the evil at the root of his policies. Here was a man who shaped “the state of opinion” on slavery. Calhoun’s political influence enshrined that slavery not should only survive, but should be expanded across North America. Even in 1860, at the onset of the Civil War, Silliman he felt that Calhoun’s policies must be overturned.

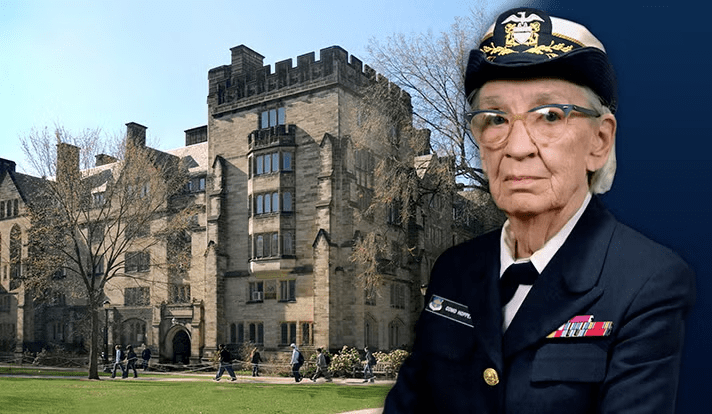

The former Calhoun College at Yale University is now named Grace Hopper College

Calhoun College at Yale Renamed Hopper College

The original name “Calhoun College” had been assigned to the residential hall in 1933 during the Depression, along with seven other residential colleges. The name change from Calhoun to Grace Hopper College was made by the administration in 2017. According to the University, the name change was very controversial because John C. Calhoun, the college’s original namesake, was a strong defender of slavery. In stark contrast, Grace Hopper was a not a politician but an esteemed mathematician. She was also a computer scientist and US Navy rear admiral, who broke resistence barriers and glass ceilings in several male-dominated fields.[2]

Rather than delving further into the life and legacy of Grace Murray Hopper, who is truly remarkable, this Witness Post has quotations from the first and subsequent statements about the Name Change, by the steadfast college administration caught in a rare state of uncertainty and hesitation. It shows a University in flux as it deliberates on an important matter of principle.

In April of 2016, after closed door sessions with the administration and the Yale Corporation — the university’s board of trustees — President Peter Salovey unequivocally stated that, despite the controversy, the name Calhoun College would remain in tact. “At that time, as now, I was committed to confronting, not erasing, our history. I was concerned about inviting a series of name changes that would obscure Yale’s past,” said Salovey.[3]

As the “heat in the kitchen” became intolerable, in August 2016, Salovey stepped out of the kitchen and asked John Witt ’94 B.A., ’99 J.D., ’00 Ph.D., the Allen H. Duffy Class of 1960 Professor of Law and professor of history, to chair a Committee to “Establish Principles on Renaming.”

Less than one year after his original statement, President Peter Salovey announced, “These concerns remain paramount, but we have since established an enduring set of principles that address them. The principles establish a strong presumption against renaming buildings, ensure respect for our past, and enable thoughtful review of any future requests for change.” Thus, with the guidance of the Witt report and three interpreters of name-changing protocols, the university determind it would honor one of Yale’s most distinguished graduates, Grace Murray Hopper ’30 M.A., ’34 Ph.D., by renaming Calhoun College after her.

The Final Decision

The Yale Corporation made its final decision at its 2017 annual meeting. President Salovey verbally affirmed their statements: “The decision to change a college’s name is not one we take lightly, but John C. Calhoun’s legacy as a white supremacist and a national leader who passionately promoted slavery as a ‘positive good’ fundamentally conflicts with Yale’s mission and values,” Salovey went on to report: “I have asked Jonathan Holloway, dean of Yale College, and Julia Adams, the head of Calhoun College, to determine when this change best can be put into effect.”[3]

Without further public deliberation, the Calhoun name was removed and the college was renamed to honor Grace Hopper.

So who made the ultimate name change decision? Was it the university or society writ large? Society today (as espoused by the Whit report) holds sway. Universities, afterall, are not monoliths, but creations of human interation and reaction. Interesting times like these may look very different through the lenses of the generations to come, or not. Time will tell.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_C._Calhoun

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_Hopper_College

[3] https://news.yale.edu/2017/02/11/yale-change-calhoun-college-s-name-honor-grace-murray-hopper-0