Witness Post: Climbing that Tree

Henry Cotheal Evans, Background

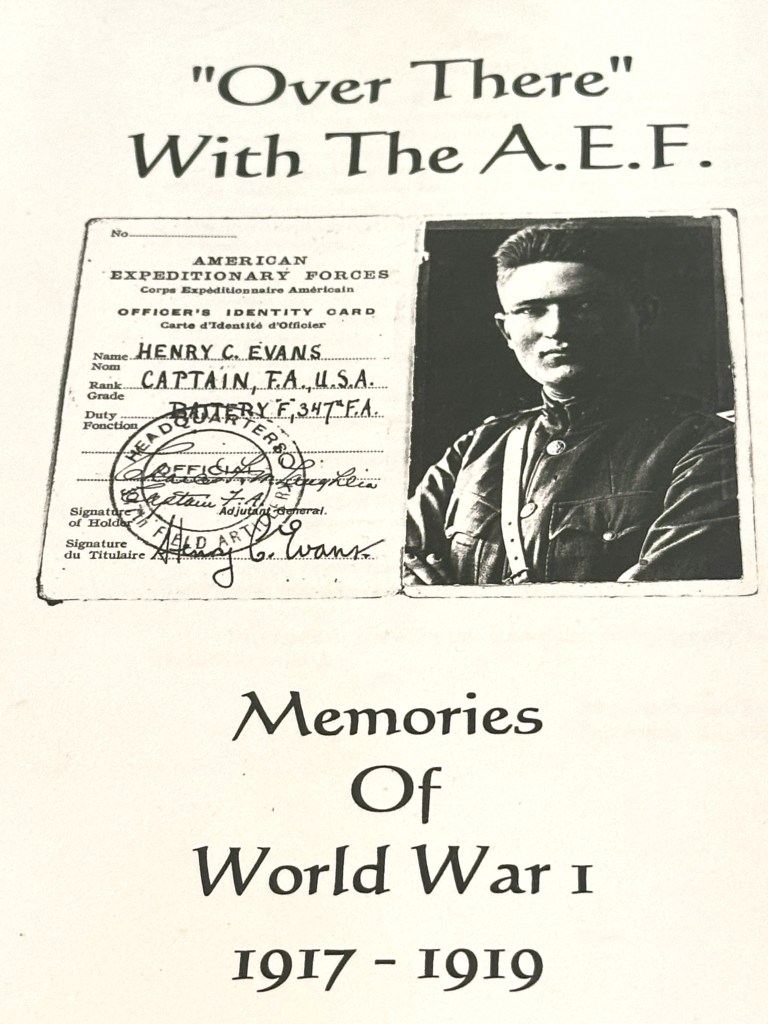

Our mother’s father, Henry Cotheal Evans (HCE), was a highly decorated war hero from two World Wars. He had served in the American Expeditionary Forces while in France during WWI (1917-1919), [1] and in Italy and North Africa under Gen. Patton in WWII (1941-1945). And he had the medals to prove it. Between and after the wars, during the peace-time years, Evans enlisted in the Maryland National Guard. His professional career was as a banker and investment banker in Baltimore, Maryland.

The 1960s

As elementary school kids my brothers and I would spend Thursday nights with our grandparents. Our grandfather (we called him Pa) would pick us up after choir practice at the Cathedral and bring us back to their house for the last moments of studying and homework, then baths and bedtime. The next day our grandmother would offer us breakfast (softboiled egg in the shell & toast), make us lunch (soggy tunafish sandwiches, wrapped in waxed paper) and drive us to school a few blocks away. We loved the ritual of it.

Over the mantle in the Evans family study was a framed collection of medals that Pa had been awarded for his heroics in both wars. I distinctly remember one conversation I had with him on a Thursday night about a particular medal in his collection. It was not an ordinary medal; it had a notable blue, red and white ribbon on top with the clasp and an Eagle suspended on a cross and landing on a wreath.

There are at least two sides to this story: my childhood memory and the facts. I remember that the medal had something to do with climbing a tree, but had only a few real specifics. And with that disclaimer, here are the words I remember Pa Evans saying (short and sweet), and what he had written for the record in his personal journal. Both versions are reported in this Witness Post. The actual journal entry gives us a glimpse into the mind of a young American soldier in enemy territory.

What I Recall HCE Saying:

Q: Can you tell me about that medal with the eagle you earned?

A: That medal there (pointing to the DSC) has a good story.[2] I was in France serving with the Expeditionary Forces. We were pinned down by enemy fire and we could not see where the Germans were positioned. They had a machine gun. So, I climbed a tree to see over the ridge, spotted them and their guns. I relayed a message to our artillary, who fired on the Germans and soon our forces sent them running. For my tree climbing and spotting skills, the French gave me that medal.

What Henry Evans (HCE) Wrote in his Journal:

Below is the story of what really happened ….

This was War: Setting the Scene

The German machine gun bullets skipped all around us but, luckily none of us were hit. We soon made our way through the Moroccan lines and they looked at us as though we were crazy – marching directly in from the German lines toward them. We got back to the Batteries and brought them up into new positions in the middle of a large wheat field, west of Missy-aux-Bois ….

The positions that we had taken up were in an old German trench and that afternoon, as we had very little fighting to do, we tried to get some sleep. After getting the position in order, we let the men take turns catching a few hours nap. We slept down in the old German trenches, which was a big mistake, as we all were covered with cooties when we woke. We found that the German cooties were much larger and much heartier than French, American, British, Moroccan or Algerian cooties. They showed their nationality as each one had a distinct iron cross on its back.

That afternoon a Regiment of French Calvary came up with the idea of breaking through the line and cutting off the Germans’ lines of communication. However, there was so much barbed wire all over the fields that it was hard to see how they could do very much. The French dismounted and waited in the field not far from us and pretty soon some German airplanes came over and the German Artillery opened up on them, adjusted by the German plane. The slaughter was terrific, until they pulled the French Cavalry out again and sent it back.

The next morning early, we moved forward to new positions at Missy-aux-Bois. On the way, I ran into some of the 26th Infantry, who were moving back into reserve and found Jim Manning in command. I stopped and talked to him for a few minutes, as we went by. That afternoon he went back into the lines and was wounded.

Finding a View Point

When we got into our new position, we were told that the advance of the Infantry had been held up by German machine guns and to endeavor to fire on the Germans. We were unable to get any information as to the location of our own front line or the location of the enemy. I sent Lieutenant Cheston forward to try to find out something. He came back in a little while reporting that it was impossible to see the German front lines without going on the crest of a hill, which was in plain view and was being swept by enemy fire so thoroughly that it was impossible to get there. Cheston had tried climbing a tree from the top of which he thought he could see over the hill, but found the machine gun fire on the tree so heavy that he felt it was suicide to climb up.

Climbing the Tree & Signalling

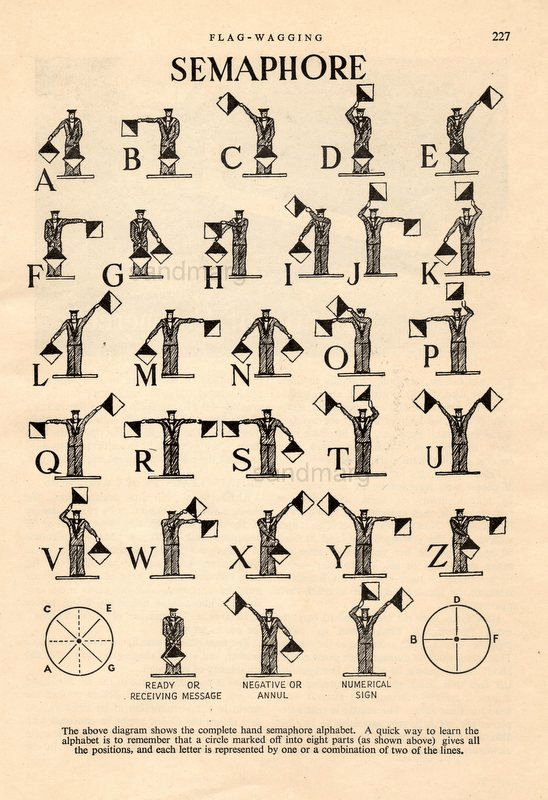

I had a terrible headache all morning, principally from lack of sleep but decided to make a try at locating the enemy anyway. A tank had run over most of our telephone wire and we did not have enough left to run a line to the observation post. I finally climbed into one of the trees along the Soissons-Paris road and found that I could see the enemy position clearly from high up in the tree. I had Corporal Scully with me who had a pair of semaphore flags and I called down data to him. He semaphored the data back to Sergeant Blalock, who had climbed up on top of the rudder of a German airplane that had crashed nose down in a field nearby. He relayed the messages to Sergeant Karns who was on a small hill near the Battery.

We got a few artillery shots off that landed close to the German machine guns and apparently they saw me and [Scully] the semaphore man at the base of the tree. They turned the works on the tree and it was lucky that the trunk of the tree was large enough so that we could get completely behind it, except for one arm that I had to expose in order to hold on. Once, when I was peering out around the tree in order to observe the shots, a machine gun bullet clipped off a leaf that was attached to a branch that was touching the side of my head and a number of shots hit the trunk of the tree within a few inches of my hand. Whether the firing arriving from the Infantry to the tree had anything to do with it or whether the Artillery fire on the machine guns had anything to do with it, I do not know, but, in any event, at about that time the Allied Infantry dashed forward and rushed over the machine guns. I got out of the tree as quickly as I could and Scully and I went back to the Battery.

What I Wish Now in 2025:

I have so many wishes from those times and today, it is hard to separate them. Our Thursday nights with Pa and Grandma Evans were in the early 1960’s and Pa’s tree climbing heroics were nearly a half century earlier. Pa had also had five heart attacks before we spent those nights with him. He was mostly deaf, due to the many artillery shells that were fired in close proximity. Yet, he had such amazing stories to tell, such heroism to explain.

I wish I had had more than an abbreviated glimpse into his life, his decision making process, and his sense of justice. So many thoughts and dispositions from this man must have been crystalized in War. Yet I know so little about him. Yes, all of the thirty-three grandkids know the facts: Henry C. Evans was decorated as a Captain at the end of WWI and as a General at the end of WWII. He served under Generals Pershing, Patton and Eisenhower. He fought in “the Battle of the Bulge” in the Ardennes Forests of Eastern Europe. He was a man of integrity and principle. His family was dedicated to service to our country: Two of his sons (our uncles) attended The Military Academy at West Point and served in the conflicts in Korea and the War in VietNam. Two of his daughters (our aunts) were nurses. There is an Armory in Maryland named in Henry C. Evans’ honor. Yet these are just facts; there is so much more between the lines.

My parents named me after him. So, what do I wish? I wish I knew him better. I wish I could tell the stories with more accuracy and respect for this man and his times. I wish I knew what made him tick. Certainly by his actions, he lived his justifications for war and can be honored for the principles he upheld with his precious time among us.

We need more men like HCE among our elders, living in our midst!

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

[1] From an Evans Family memoir written by Henry Cotheal Evans, entitled “Over There“ With the A.E.F.: Memories of World War I (1917-1919), Army University Press. The medals above are not Pa Evans’ but some replicas for visual affect.

The Climbing the Tree Story is copied nearly verbatim from his (HCE) Journal, pages 53-54.

[2] The medal that H.C. Evans was awarded was the Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.), as cited below in the local newspaper:

Henry C. EVANS TO GET D.S.C. FOR HEROISM

Baltimorean Cited for Extraordinary Episode in France During War Under Fire While in Tree.

Also Declared to have Inspired His Men By His Coolness When in Danger.

Henry C. Evans, son of Frank G. Evans, vice-president of the Eutaw Savings Bank, and an officer of

the Field Artillery Officers’ Reserve Corps, yesterday was cited by the War Department for the Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.)

He is to be decorated, the War Department announced, for “extraordinary heroism at Chaudon,

France, while serving as first lieutenant in the Sixth Field Artillery, First Division.”

The particular episode for which Mr. Evans was cited occurred July 9, 1918.

The citation reads as follows:

“Henry C. Evans, captain, Field Artillery Officers’

Reserve Corps, then first lieutenant, Sixth Field

Artillery, First Division, for extraordinary heroism in

action near Chaudon, France, July 9, 1918. Learning

that the advance of the infantry which his battery was

supporting was meeting with stubborn resistance,

Lieutenant Evans voluntarily went forward through

artillery and machine gun fire to the crest of a hill

and climbed a tree overlooking the enemy position

for the purpose of adjusting fire upon the enemy.

Though subjected to severe fire from hostile artillery

and machine guns, he remained courageously in this

exposed position and this was able to direct the fire of

his battery materially, so as to assist in the advance of

the infantry.”

Toward the end of the war, he was cited again,

this time by his division commander, Major General

McGlachlin. He was commanding his battery in

the Argonne-Meuse battle, and among General

McGlachlin’s citations of his men “for conspicuous

gallantry and heroism” was this paragraph:

“First Lieutenant. Henry C. Evans, Sixth Field

Artillery, during an intense enemy bombardment of a

battery position, went from piece to piece, giving the

crews the data for continuing the rolling barrage in

support of the Infantry and inspiring his men by his

coolness and disregard of personal danger.”

Mr. Evans got into the war before the American

armies started across. He went to France in May, 1917;

served in the French Motor Transport Service; was

commissioned second lieutenant of United States Field

Artillery in October, 1917, and was assigned to the

First Division.

He saw service in every major engagement in

which American troops fought in France. Besides

being a reserve officer, he is captain of Battery F, One

Hundred and Tenth Field Artillery, Maryland National

Guard. He lives in Calvert Court Apartments.