Suddenly Seventy: X

No, this Suddenly Seventy Post is not about Elon Musk, and the not-so new name for Twitter.

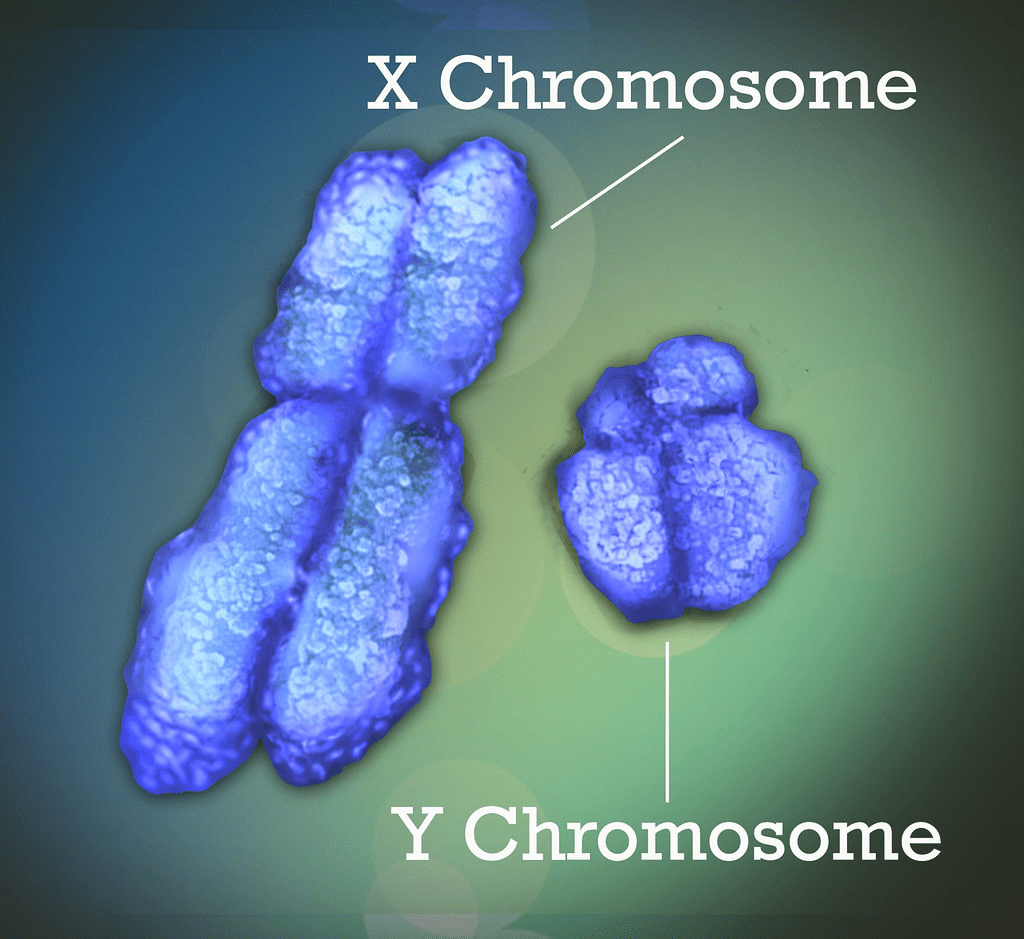

It is about the human body and X, as in X chromosomes.

What is it?

The X chromosome is one of the two sex chromosomes in many organisms, including mammals. It is found in both males and females. It is a part of what is called “The XY Sex-Determination System” or XO sex-determination system. The X chromosome was named for its unique properties by early researchers, which resulted in the naming of its counterpart Y chromozome, for the next letter in the alphabet, following its subsequent discovery.

According to Wikipedia,[1] the X chromosome was first noted as ‘special’ in 1890 by Hermann Henking in Leipzig, Germany. Henking was studying the testicles of Firebugs (Pyrrhocoris) and noticed that one chromosome did not take part in meiosis. Chromosomes are so named because of their ability to take up staining (chroma in Greek means color). Although the X chromosome could be stained just as well as the others, Henking was unsure whether it was a different class of the object and consequently named it X element, which later became X chromosome after it was established that it was indeed a chromosome.

The idea that the X chromosome was named after its similarity to the letter “X” is mistaken. All chromosomes normally appear as an amorphous blob under the microscope and take on a well-defined shape only during mitosis. This shape is vaguely X-shaped for all chromosomes. It is entirely coincidental that the Y chromosome, during mitosis, has two very short branches which can look merged under the microscope and appear as the descender of a Y-shape.

It was first suggested that the X chromosome was involved in sex determination by Clarence Erwin McClung in 1901. After comparing his work on locusts with Henking’s on Firebugs and others, McClung noted that only half the sperm received an X chromosome. He called this chromosome an accessory chromosome, and insisted (correctly) that it was a proper chromosome, and theorized (incorrectly) that it was the male-determining chromosome.

The eXceptional nature of the X chromosome

According to Balaton, Dixon-McDougall, Peeters & Brown, as written in a paper published in the Oxford Journals on Human Genetics, the X chromosome is unique in the genome.[2] This article goes deeply into the science here, too deeply perhaps, so feel free to skip to the end.

In recent years there have been advances in our understanding of the genetics and epigenetics of the X chromosome. The X chromosome shares limited conservation with its ancestral homologue the Y chromosome and the resulting difference in X-chromosome dosage between males and females is largely compensated for by X-chromosome inactivation. The process of inactivation is initiated by the long non-coding RNA X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) and achieved through interaction with multiple synergistic silencing pathways. Identification of Xist-interacting proteins has given insight into these processes yet the cascade of events from initiation to maintenance have still to be resolved. In particular, the initiation of inactivation in humans has been challenging to study as: it occurs very early in development; most human embryonic stem cell lines already have an inactive X; and the process seems to differ from mouse. Another difference between human and mouse X inactivation is the larger number of human genes that escape silencing. In humans over 20% of X-linked genes continue to be expressed from the otherwise inactive X chromosome. We are only beginning to understand how such escape occurs but there is growing recognition that escapees contribute to sexually dimorphic traits. The unique biology and epigenetics of the X chromosome have often led to its exclusion from disease studies, yet the X constitutes 5% of the genome and is an important contributor to disease, often in a sex-specific manner.

Introduction to the X Chromosome

The genomes of males and females differ dramatically, with males having a single X chromosome and the sex-determining Y chromosome; whereas females have two X chromosomes, and thus 100 Mb more DNA than males (X: ∼155 Mb, Y: ∼55 Mb). The X and Y are derived from an ancestral pair of autosomes, but the human Y retains functionality for only 17 of the over 600 genes once shared with the X. Whether there is upregulation of X-linked genes to maintain equivalence to ancestral autosomal gene dosage remains controversial, in part due to the unique gene composition of the X. Both the X and Y have acquired ampliconic gene families that are expressed only in testes, are not well-conserved between humans and mice, are often palindromic and are argued to underlie dramatic selective sweeps on the X. The X has also been both recipient and donor for retrogenes, with autosomal copies of X-linked genes compensating for the X silencing that occurs during meiotic sex chromosome inactivation (MSCI) in spermatogenesis. miRNA genes are also over-represented on the X, and respond differentially to MSCI during spermatogenesis. Regardless of whether the X to autosome dosage has equilibrated, there is a dosage imbalance between males and females for the ∼1000 X-linked genes. As hypothesized by Lyon in 1961, compensation for this difference occurs by inactivation of one of the two Xs in early female development.

So What Does That Mean to ME???

In simple terms women live five years longer, on average, than their male counterparts. Many scientists believe that the secret to human longevity lies in that second X chromosome.

So boys? Your longevity may have more to do with your mother’s X chromozome, and her menopause than with your diet or your exercise or your own Y. The research at NIH is now all stopped by the feckless Trump administration. And it appears it will remain that way until the old bastards realize that they want to live longer too.

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X_chromosome

[2] Balaton, Dixon-McDougall, Peeters & Brown, The eXceptional nature of the X chromosome, as written in a paper published in the Oxford Journals on Human Genetics, April, 2018.