Clarence Edward Dutton (1941-1912)

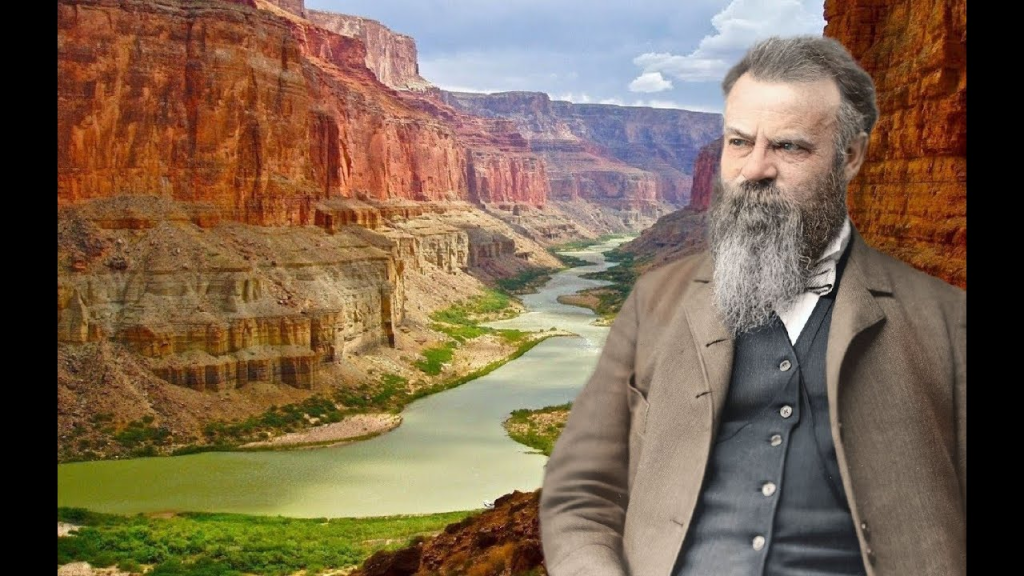

Powell’s Pals: Capt. Clarence E. Dutton

Clarence Edward Dutton was an American geologist and a US Army officer. Dutton was born in Wallingford, Connecticut in May, 1841. He was educated in his home state and graduated from Yale College in 1860. Dutton took postgraduate courses at Yale until 1862, when he enlisted in the 21st Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. He joined the northern forces as second lieutenant. He later fought at three Civil War battles in Virginia (Fredericksburg, Suffolk, Petersburg) and one in Tennessee (Nashville). He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 1871.[1]

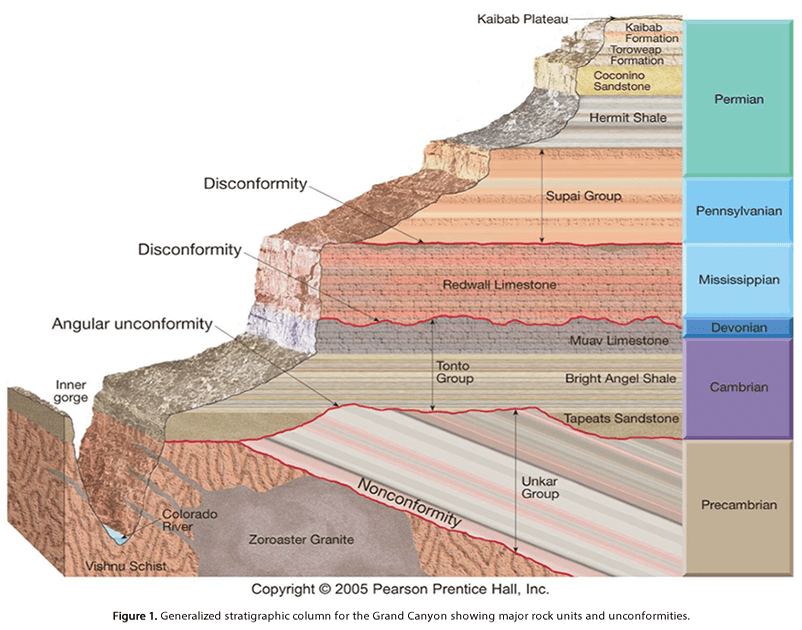

After the Civil War, he developed a deep, personal interest in geology. In 1875, he began work as a geologist for the US Geographical & Geological Survey, under the leadership of John Wesley Powell [2]. Working chiefly in the Colorado Plateau and the Rocky Mountain region, Dutton spent 10 years exploring the plateaus of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. To put Dutton’s work ethic and output into context, he was described as “an energetic and effective field geologist.” That said, over a two year period (1875–1877) Dutton’s field party mapped 12,000 square miles (31,000 km2) of the high plateaus of southern Utah, an area of intensely rugged topography and extraordinarily poor access. He wrote several classic papers, including geological studies of the high plateaus of Utah (1879–80), and the Cenozoic history [3] of the Grand Canyon district (1882).

In 1878, he was one of the ten founding members of the Cosmos Club. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1884.

In 1886, Dutton led a USGS exploratory party to Crater Lake, Oregon, which is the ancient site of a collapsed volcano. His team carried a half-ton survey boat, the Cleetwood, up the steep mountain slope of the cinder cone. They then lowered it 2,000 feet (610 m) onto the lake. From the Cleetwood, Dutton used piano wire with lead weights to measure the depth of the lake at 168 different points. The survey team determined the lake was 1,996 feet (608 m) deep. The currently-accepted maximum depth figure, measured by sonar, is 1,943 feet (592 m). Pretty darn good for government work.

View of Crater Lake from Dutton Ridge

Also in 1886 Dutton was pulled aside from his other geologic responsibilities to investigate the earthquake in Charleston, South Carolina. As head of the division of volcanic geology at the USGS, he studied volcanism in the states of South Carolina, Hawaii, California, and Oregon. (Congress chided Maj. John Wesley Powell for sending Dutton to Hawaii, which felt foolish to those on Capitol Hill — Hawaii was a far away island archipelago, at that time.)[8]

Internationally he helped coordinate the scientific response to a large earthquake in the Mexican state of Sonora in 1887. Through these studies of lava events, he investigated the volcanic action that caused the uplifting, sinking, twisting, and folding of the Earth’s crust. In his research he advanced a method for determining the depth of the focal point of an earthquake and for measuring, with unprecedented accuracy, the velocity of waves.

In 1889, Dutton was asked questions by Congress on the appropriateness of John Wesley Powell’s Irrigation Survey. Having trained a full staff of hydrology engineers for the Survey, Powell was both surprised and wounded that Dutton stated before Congress that he was skeptical of the amount of the USGS budget dedicated to topography. The testimony severely undermined the topography maps that were the basis of the irrigation surveys of 1888. Once an ally, who had been a loyal friend and collaborator for over 15 years, Dutton was now squarely squatting in another camp. [4]

Dutton used his research to propose his principle of isostasy in the paper: “On Some of the Greater Problems of Physical Geology” (1892). In 1904 he published the semipopular treatise called Earthquakes in the Light of the New Seismology. Late in his career Dutton concluded that lava is liquefied by the heat released during decay of radioactive elements and that it is forced to the surface by the weight of overlying rocks.[5]

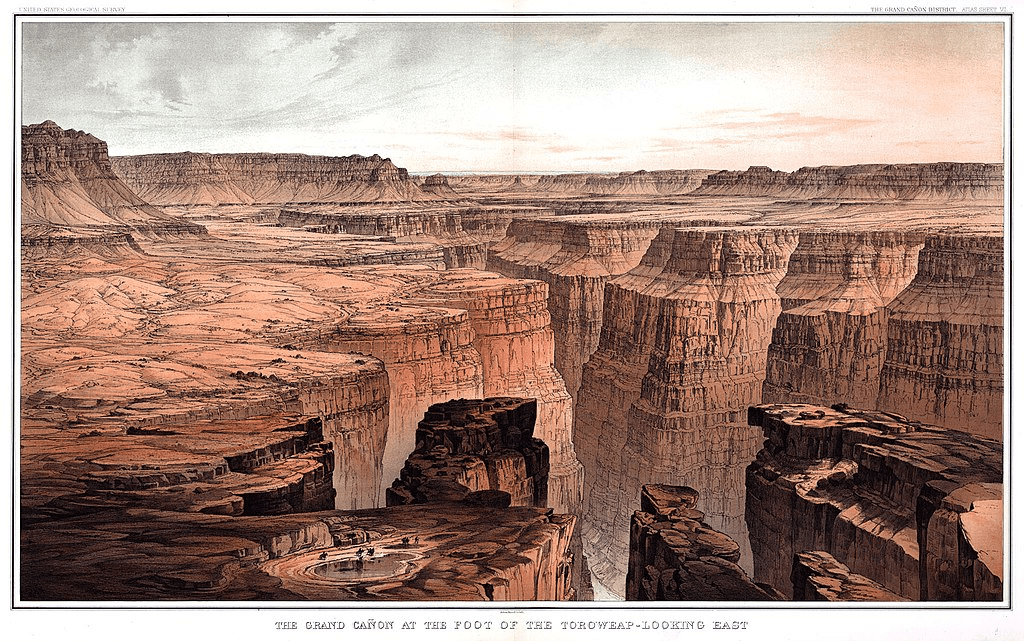

Time out for Point Sublime & Toroweap Valley

One of the key characteristics of this Pal of Powell, is that he was a Word Smith. He could whip up a good story and tell it in a romantic way, as few other scientists could do. Read the following description of a part of the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, known as Point Sublime:

“Wherever we reach the Grand Cañon in the Kaibab, it bursts upon the vision in a moment. Seldom is any warning given that we are near the brink. At the Toroweap it is quite otherwise. There we are notified that we are near it a day before we reach it. As the final march to that portion of the chasm is made the scene gradually develops, growing by insensible degrees more grand until at last we stand upon the brink of the inner gorge, where all is before us. In the Kaibab the forest reaches to the sharp edge of the cliff and the pine trees shed their cones into the fathomless depths below.”

The Toroweap Valley: “At the witches water pocket”

“In every desert the watering places are memorable, and this one is no exception. It is a weird spot. Around it are the desolate Phlegnean fields, where jagged masses of black lava still protrude through rusty, decaying cinders. Patches of soil, thin and coarse, sustain groves of cedar and piñon. Beyond and above are groups of cones, looking as if they might at any day break forth in renewed eruption, and over all rises the tabular mass of Mount Trumbull. Upon its summit are seen the yellow pines (P. ponderosa), betokening a cooler and a moister clime. The pool itself might well be deemed the abode of witches. A channel half-a-dozen yards deep and twice as wide, has been scoured in the basalt by spasmodic streams, which run during the vernal rains. Such a stream cascading into it has worn out of the solid lava a pool twenty feet long, nearly as wide, and live or six feet deep. Every flood fills it with water, which is good enough when recent, but horrible and stagnant when old. Here, then, we camp for the night.”

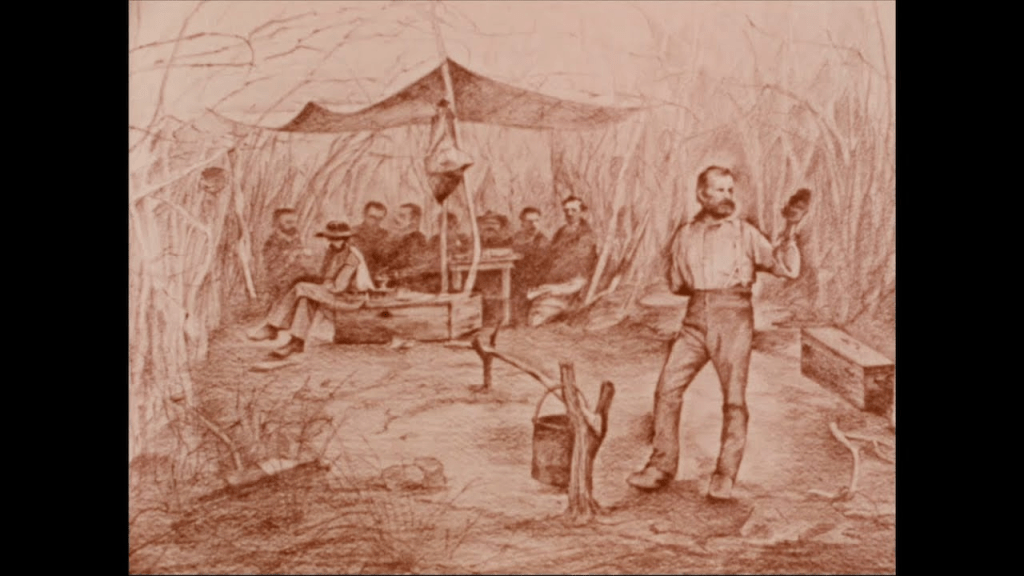

Image of one-armed John Wesley Powell, as his crew rested beneath a tarp

Dutton certainly had a distinctive flair for literary description, and he is perhaps best remembered today for his colorful (and sometimes flamboyant) descriptions of the geology and scenery of the Grand Canyon region and of Arizona. “Dutton first taught the world to look at that country and see it as it was … Dutton is almost as much the genius loci [6] of the Grand Canyon as John Muir is of Yosemite” – Wallace Stegner, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian.

Dutton’s writing would be considered florid by many modern readers, but as one of the first scientific reporters on the Grand Canyon, he can perhaps be forgiven. His exuberance at the scenes he saw was unbridled. AND the views were astonishing.

At length the sun sinks and the colors cease to burn. The abyss lapses back into repose. But its glory mounts upward and diffuses itself into the sky above. Long streamers of rosy light, rayed out from the west, cross the firmament and converge again in the east ending in a pale rosy arch followed by the darkening pall of gray, and as it ascends, it fades and disappears, leaving no color except the after-glow of the western clouds, and the lusterless red of the chasm below. Within the abyss the darkness gathers. Gradually the shades deepen and ascend, hiding the opposite wall and enveloping the great temples. For a few moments the summits of these majestic piles seem to float upon a sea of blackness, then vanish in the darkness, and, wrapped in the impenetrable mantle of the night, they await the glory of the coming dawn.

— Clarence Dutton, The Chasm in the Kaibab

At the same time, John Wesley Powell had a lot of writing flair as well. His naming techniques of one of the most magnificent cliffs in the Canyons of the Colorado River prove the point:

“Starting, we leave behind a long line of cliffs, many hundred feet high, composed of orange and vermilion sandstones. I have named them Vermilion Cliffs. When we are out a few miles, I look back, and see the morning sun shining in splendor on their painted faces; the salient angles are on fire, and the retreating angles are buried in shade, and I gaze on them until my vision dreams, and the cliffs appear a long bank of purple clouds, piled from the horizon high into the heavens.”

Dutton went on to publish many papers and to invest some new geological theories. Some of his writings are listed below [7]. He also is credited with inventing the Raisin Theory – A theory that explains how the earth likened to a grape that contracted into a raisin due to a cooling process. 13.77 Billion Years Ago – When did the cooling process occur? Clarence Edward Dutton – An American seismologist and geologist that explained the contract Earth concept thru Isostacy.

In 1891 Dutton retired from the USGS to serve as commander of the arsenal of San Antonio, Texas; then as ordnance officer of the USGS department of Texas. After retiring from the Army in 1901, he returned to the study of geology. Dutton spent his last years at the home of his son in Englewood, New Jersey. He died in 1912 and was buried in a grave with his sister, Marion Dutton Prime (who died in 1903).

Dutton Family Gravesite

The ungulation of the sandstone is a mystical as it is facscinating. How do you think it was formed?

Map of the Colorado Plateau

John Wesley Powell with image of the Colorado River below him.

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clarence_Dutton

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Wesley_Powell . The title of the USG&GS was later shortened to the USGS (US Geological Survey).

[3] Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, Penguin Books, 1954.

[4] The Cenozoic Era, spanning from 66 million years ago to the present, is known as the “Age of Mammals.” The Era is characterized by the rise of mammals and flowering plants following the asteroid impace that ended the Mesozoic Era. Key events include the continents moving with the tectonic plates to their current positions, the formation of major mountain ranges like the Himalayas, and the evolution of humans from primates. The era is divided into the Paleogene, Neogene, and Quaternary periods, witnessing significant shifts in global climate, with periods of warming followed by cooling and the onset of the Ice Ages.

[5] In a footnote to an 1882 review in the American Journal of Science, Dutton coined the term “isostasy.” He later stated: “In an unpublished paper I have used the terms isostatic and isostacy (sic) to express that condition of the terrestrial surface which would follow from the flotation of the crust upon a liquid or highly plastic substratum – different portions of the crust being of unequal density.” Thus, he realised that there is a general balance within the Earth’s crust, with lighter weight blocks coming to stand higher than adjacent blocks with higher density, an idea that was first expressed by Pratt and Airy in the 1850s. Dutton elaborated these ideas seven years later in his address to the Philosophical Society of Washington in 1889. When this theory was printed in 1892, the term isostasy was formally proposed. On the advice of some Greek scholars, Dutton changed the ‘c’ in the key term to an ‘s’. Going forward the condition would be known as ISOSTASY.

[6] Genius Loci, Latin expression that Stegner used to describe both John Muir and Clarence Dutton.

[7] Notable Dutton publications include:

- 1880, Report on the Geology of the High Plateaus of Utah. U.S. Geog. and Geol. Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, vol. 32, 307 pp. and atlas.

- 1882, Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon District. U.S. Geol. Survey Monograph 2, 264 pp. and atlas.

- 1884, Hawaiian Volcanoes. U. S. Geol. Survey, 4th Ann. Rpt., pp. 75–219.

- 1889, The Charleston Earthquake of August 31, 1886. U.S. Geol. Survey, Ann. Rpt. 9, pp. 203–528.

- 1889, On Some of the Greater Problems of Physical Geology. Bull. Phil. Soc. Wash., 11:51–64. Proposed the new term isostasy.

- 1904, Earthquakes, in the light of the new seismology

[8] Clarence Dutton was one of the men with whom John Wesley Powell found some of his strongest kinship. The exploration of the relationship is outlined and discussed in another Powell’s Pals post on Dutton and eight other scientists and explorers from the Powell era.