O. Henry: Dyslexia

Reading aloud in school was one of the most terrifying public experiences of my life. The easy cadence of fluency always evaded my speaking voice, as I hunted for safe, recognisable words and struggled with the multi-syllabic others. Small, easy words were left out entirely, making sentences with the words “not” or “must” and ”God” bungled and misunderstood. As a dyslexic, comprehension was elusive and demoralising. Self esteem was a mirage.

In a phrase, school was a dreaded place where teachers eyed me with suspicion and the cool, smart kids whispered their tut-tuts. I felt like a target for their jokes and ridicule. My biggest adolescent stress came with standing elecution lessons and spelling bees; and lets just say that phonics was not my jam.

Meanwhile on the grading front, teachers labeled me early, “If he works really hard and applies himself, he might earn a passing grade.” I seemed predestined as a “C” or below student. All the while I wallowed in the lowest reading group. And, since a ton of elementary math calculations were based on word problems and language skills, I also landed in the lowest math section.

Memorization was a high hurdle for me, but my mom cajoled me to tackle math facts and get Cub Scout badges in the process. She said sticking with it was critical. So I did. My parents, at the advice on our pediatrician, removed me from piano lessons, feeling it was “another language that would frustrate me further and torpedo my self worth.” Ironically, more than others in my family, I pursued singing and music to a high level.

Finally in the 8th grade, after eight years of failure, everyone was marvelling at my ascendancy to tackle and master algebra. Especially me.

Early Education

My early education was a painful story of the diagnosis, treatment, and “practice-reading drills.” I ended up hating reading and would do anything I could to avoid it. That ended around the time I had tackled algebra. In the case of reading my transformation came from the book, The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien.

I was sick over the summer and spent many hours lying on a swing we had on a back screened porch. My parents had given me a book to read for the month of July. Out of boredom, I picked it up and started reading. Loving the story, I read that Tolkein had some other books in a Trilogy. My parents bought me The Lord of the Rings, and the daily practice helped to derail my impending reading challenges and embrace the ability of reading to take me to another land.

In college I took educational psychology classes and learned about reading disorders. My unintended major of ed psych was an accident. In the end it was really about self-discovery.

Below are some questions and answers put forward by the Cleveland Clinic and other reputable sources to help demystify this learning disability and put a bright light on this condition which impacts up to 20% of the population worldwide. [1]

What is Dyslexia?

The International Dyslexia Association defines dyslexia as “a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction.” In other words, dyslexia is a language based learning difference that affects a person’s ability to connect letters to sounds, making it hard to read and spell. A person with dyslexia will read below what would be expected despite having normal or even above average intelligence. Dyslexia can also look different in each individual and can range from mild to moderate in severity.

Dyslexia is a learning disability that makes reading and language-related tasks harder. It happens because of disruptions in how your brain processes writing so you can understand it. Most people learn they have dyslexia during childhood, and it’s typically a lifelong issue. This form of dyslexia is also known as “developmental dyslexia.”

Dyslexia falls under the umbrella of “specific learning disorder.” That disorder has three main subtypes:

- Reading (dyslexia).

- Writing (dysgraphia).

- Math (dyscalculia).

How dyslexia affects language understanding

According to the Cleveland Clinic, [2] reading starts with spoken language. In early childhood, speaking starts with making simple sounds. As you learn more sounds, you also learn how to use sounds to form words, phrases and sentences. Learning to read involves connecting sounds to different written symbols (letters).

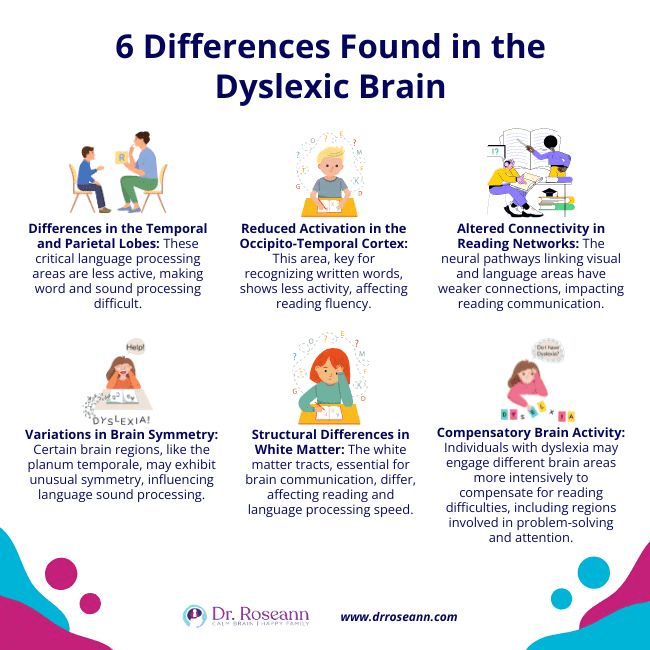

This is where dyslexia enters the picture. It interferes with how your brain uses spoken language to “decode” writing. Your brain has trouble processing what you read, especially breaking words into sounds or relating letters to sounds when reading.

That slowdown in processing can affect everything that follows. That includes:

- Slowed reading because you have trouble processing and understanding words.

- Difficulties with writing and spelling.

- Problems with how you store words and their meanings in your memory.

- Trouble forming sentences to communicate more complex ideas.

How common is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is uncommon overall but widespread enough to be well-known. Experts estimate it affects about 7% of people worldwide. It affects people equally regardless of sex and race.

However, many people have symptoms that aren’t severe enough for diagnosis. Including people with symptoms but without a diagnosis, dyslexia may affect up to 20% of people worldwide.

Symptoms and Causes:

What causes dyslexia?

The exact cause of dyslexia isn’t clear. However, several clues hint at how and why most cases happen.

- Genetics. Dyslexia is highly genetic and runs in families. A child with one parent with dyslexia has a 30% to 50% chance of inheriting it. Genetic conditions like Down syndrome can also make dyslexia more likely to happen.

- Differences in brain development and function. If you have dyslexia, you’re neurodivergent. That means your brain formed or works differently than expected. Research shows people with dyslexia have differences in brain structure, function and chemistry.

- Disruptions in brain development and function. Infections, toxic exposures and other events can disrupt fetal development and increase the odds of later development of dyslexia.

Risk factors

Several risk factors can contribute to whether someone develops dyslexia. They include (but aren’t limited to):

- Toxic exposures. Air and water pollution can increase your risk of developing dyslexia. This is especially true with heavy metals (like lead or manganese), nicotine and certain chemicals used as flame retardants.

- Lack of access to reading material. The risk of developing dyslexia is higher for children who grow up in households where reading isn’t encouraged or where reading material is less available.

- Learning environment limitations. Children with less learning support in school or similar environments are more likely to develop dyslexia.

What are the signs and symptoms of dyslexia?

As a child gets older, dyslexia can often look like:

- Difficulty spelling simple words.

- Trouble learning the names of letters.

- Problems telling apart letters with similar shapes, such as “d” and “b” or “p” and “q.”

- Trouble rhyming.

- Reluctance to read aloud in class.

- Trouble sounding out new words.

- Trouble associating sounds with letters or parts of words.

- Trouble learning how sounds go together.

- Mixing up the position of sounds in a word.

Having one of the above doesn’t mean a person has dyslexia, but if they’re having trouble learning the basic skills for reading, then dyslexia screening and testing is a good way to see if they need specialized help.

Dyslexia also has levels of severity:

- Mild: Difficulties are there, but you can compensate or work around them with the right accommodations or support.

- Moderate: Difficulties are significant enough that you need specialized instructions and help. You may also need specific interventions or accommodations.

- Severe: Difficulties are so pronounced that they continue to be a problem even with specialized interventions, accommodations and other forms of treatment.

Diagnosis and Tests:

How is dyslexia diagnosed?

Although dyslexia is due to differences in your brain, no blood tests or lab screenings can detect it. Instead, careful evaluation and testing of common signs identify someone with this reading problem.

Testing for dyslexia should look at:

- Decoding (reading unfamiliar words by sounding them out).

- Oral language skills.

- Reading fluency and reading comprehension.

- Spelling.

- Vocabulary.

- Word recognition.

When should I have my child tested for dyslexia?

Typically, early testing is best for learning disabilities. Your child can begin learning new reading strategies sooner with an early diagnosis. Many children show reading problems before third grade, but the reading demands increase with age, and it’s important to diagnose any learning disorder as early as possible.

Your child’s school may recommend an evaluation for learning disabilities with a certified educational psychologist. Ask the school administration for help finding one available to you.

Management and Treatment:

What treatment options exist for dyslexia?

Currently, no medications treat dyslexia. Instead, educational interventions can teach effective new ways to learn and read.

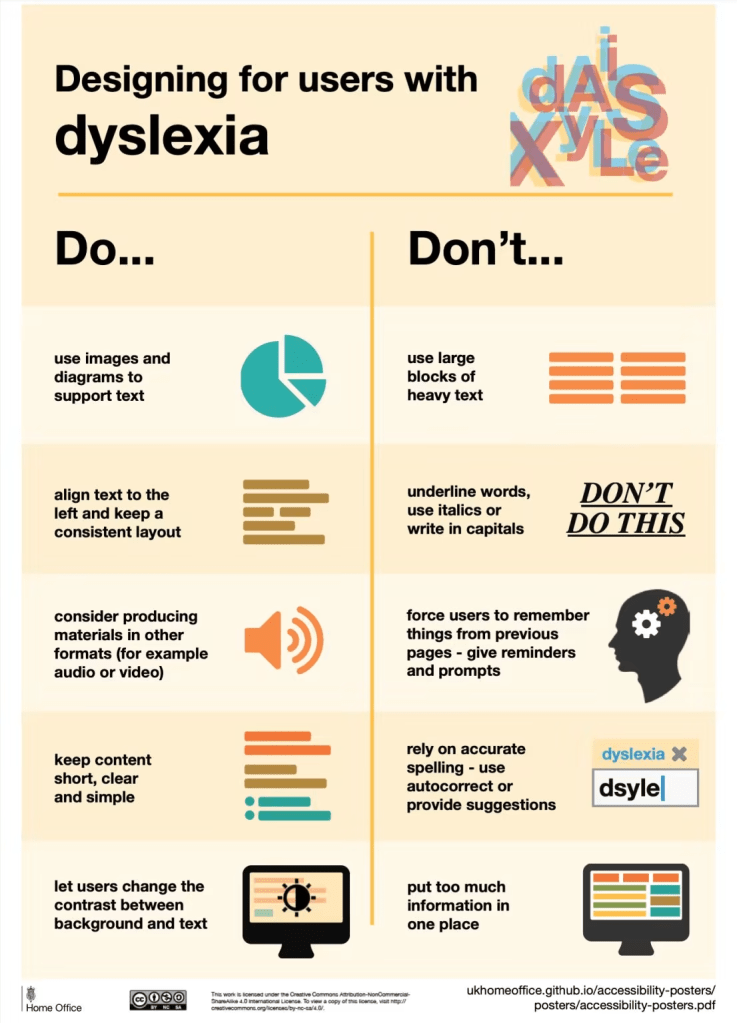

Children with dyslexia may work with a trained specialist to learn new reading skills. Sometimes, slowing down a lesson gives a child with dyslexia more time to cover topics. Work with your child’s school to ensure your child gets the education they deserve.

How can I help my child with dyslexia?

The most important thing you can do is to spend time reading aloud with your child. That time spent together can help them as they work on their reading skills.

It’s also important to remember that dyslexia isn’t something that your child has control over. Be patient and supportive. The encouragement and backing you provide can be the boost your child needs as they learn to manage their dyslexia. It can also help them feel less anxious or afraid about reading-related activities.

You can also be an advocate for your child. You and your child’s school can develop an Individualized Education Plan (called an IEP). This document sets personalized expectations and lesson plans for your child at school.

Is dyslexia in adults treatable?

Yes, adults can benefit from treatment for dyslexia. There are programs and tools available that can help you with dyslexia-related reading difficulties no matter your age.

Prevention:

How can I prevent dyslexia?

Dyslexia isn’t preventable, but it’s often manageable with different strategies for learning and reading. You should:

- Talk with a healthcare provider if you notice any early signs of dyslexia.

- Work with your child’s school to develop an individualized education plan.

- Support your child’s mental health, too, and consider mental health care if your child experiences anxiety or other issues related to their dyslexia.

Outlook / Prognosis:

What is the outlook for dyslexia?

Dyslexia often draws attention when children begin learning to read, but it isn’t always detected early. Without early diagnosis, many children struggle with reading problems throughout school and into adulthood.

When dyslexia remains undiagnosed, children struggle to succeed in school. Identifying dyslexia by second grade gives children more time to find different ways to learn and read.

Misconceptions about dyslexia have led some to believe that people with dyslexia aren’t smart. Although untrue, this assumption can have negative effects on children.

A child with dyslexia may suffer self-esteem issues or believe they aren’t intelligent. They also have a higher risk of developing mental health conditions like anxiety or depression. Positive support from parents and teachers can help a child overcome these obstacles.

Living With Dyslexia:

What does living with dyslexia mean?

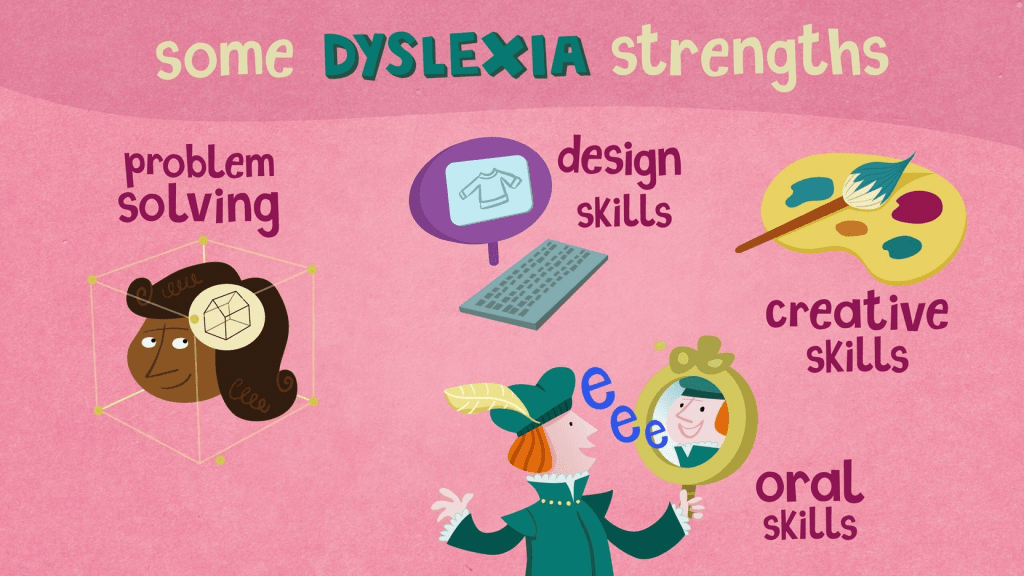

A common misconception is that dyslexia is a disease. Another misconception is that a person with dyslexia is less intelligent. Both of these ideas are false. In fact, research shows no link between intelligence and dyslexia. Many people with dyslexia go on to achieve highly in their fields of choice.

Having dyslexia means reading is hard for you, not that you’re incapable or lazy. Finding techniques to help manage dyslexia is critical to successful learning and self-esteem. Understand that having dyslexia doesn’t reflect poor intelligence.

Can you still be successful if you have dyslexia?

Yes. While dyslexia presents challenges for many who have it, there’s no shortage of high-achievers with dyslexia. Some examples of famous or very successful people with dyslexia include:

- Jennifer Anniston (actor, producer).

- Richard Branson (entrepreneur, businessperson and philanthropist).

- Cher (singer).

- Anderson Cooper (journalist).

- Tom Cruise (actor).

- Amanda Gorman (poet).

- Selma Hayek (actor, director).

- Tom Holland (actor).

- Earvin “Magic” Johnson (athlete).

- Keanu Reeves (actor, philanthropist, publisher).

- Octavia Spencer (actor, author)

- Steven Spielberg (director).

- Tim Tebow (athlete).

- Henry Winkler (actor).

Additional Common Questions

Is dyslexia a form of autism?

No, dyslexia and autism are separate conditions. Autism spectrum disorder and specific learning disorder (including dyslexia and the other two subtypes) all fall under neurodevelopmental disorders. But they aren’t the same thing. You can have both at once, but having them at the same time doesn’t mean one causes the other.

Similarly, dyslexia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are also separate conditions. Like autism, ADHD is in the same class as specific learning disorder, and you can also have both ADHD and dyslexia at the same time. However, they’re also independent of each other, meaning having both doesn’t mean one caused the other.

Is dyslexia always a learning disability?

No, dyslexia isn’t always a learning disability. While developmental dyslexia (the learning disability form) is the most common type, another type is possible but much less common.

Acquired dyslexia is a form that can develop later in life. It’s almost always due to another medical event or condition. Damage to your brain can disrupt processes like reading. It’s most common with damage from a stroke, head injury or other illness that can injure your brain.

Is dyslexia a visual problem that causes letters to appear flipped or rotated?

Sometimes, but not always. Dyslexia is a condition that can affect your perception of letters and writing. However, not everyone experiences the exact same symptoms of dyslexia.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Having dyslexia can be frustrating or embarrassing at any age. For children, it can be a major source of fear or anxiety, especially if they don’t know why they struggle to do something that others don’t have trouble with. If you or your child has dyslexia, it’s important to remember that it’s a widespread condition. It’s also not a sign that you’re less intelligent, unmotivated or lazy. It’s a difference in how your brain works. It creates challenges for you but doesn’t have to stand between you and your goals.

If your child’s teacher suspects your child has dyslexia, you can get help. Talk to your child’s healthcare provider, teacher or their school administrators and specialists to learn more about how you can help your child manage and even overcome their dyslexia.