Wilson’s Phalarope wading in a pond.

Birds: Spark Bird

May 1962, four kids in the Hooper family piled into our Ford station wagon to go “birdwatching at Druid Hill Park” in downtown Baltimore. Our mom was an avid birder, and she brought along our lone pair of binoculars for the weekend excursion. That Saturday morning we were walking with the Audubon Society, seeking views of spring migratory birds headed north to breed. The birders clustered around the Audubon guide guru as he pointed to thrushes, warblers, doves, buntings and swallows.

As the youngest birder in the brood, I got the binoculars last — well after the bird had flown. The cluster of birders had moved quickly to the next location for avian sightings and I never figured out how to focus the binoculars’ lenses, much less spot the species. I was left hopelessly cursing this avian curiosity as a waste of time.

Ten years later, I met naturalist and ornithologist, Arch McCallum. He proved an inspiring birder and nature biologist. With Arch’s prompting, I was bird-brained into changing my bias and had a change of heart. We were camping in New Mexico, and with us were two young birders, Tim Lord from Baltimore and Bryan Malcolm from Boston. For a solid month they had been seeking the positive identification of the rare Pygmy Nuthatch. Both boys already had extensive life lists with bird species from all over the US. That summer, they positively identified a Wilson’s Phalarope nesting in the marshy area of Bluewater Lake near our Base Camp outside Thoreau, New Mexico. They were reluctantly open to studying new species, when they stumbled upon the nest of the Phalarope. Their favorite bird, or Spark Bird, was immediately changed from the nuthatch to the phalarope forever.

Those two young birders were able to document their findings, including photos of the nest and eggs, which Dr. Arch McCallum helped them document for an entry in the American Birding Association magazine. The boys’ research enabled the ABA to extend the phalarope’s western nesting range by over 500 miles beyond its previous west Texas limits.

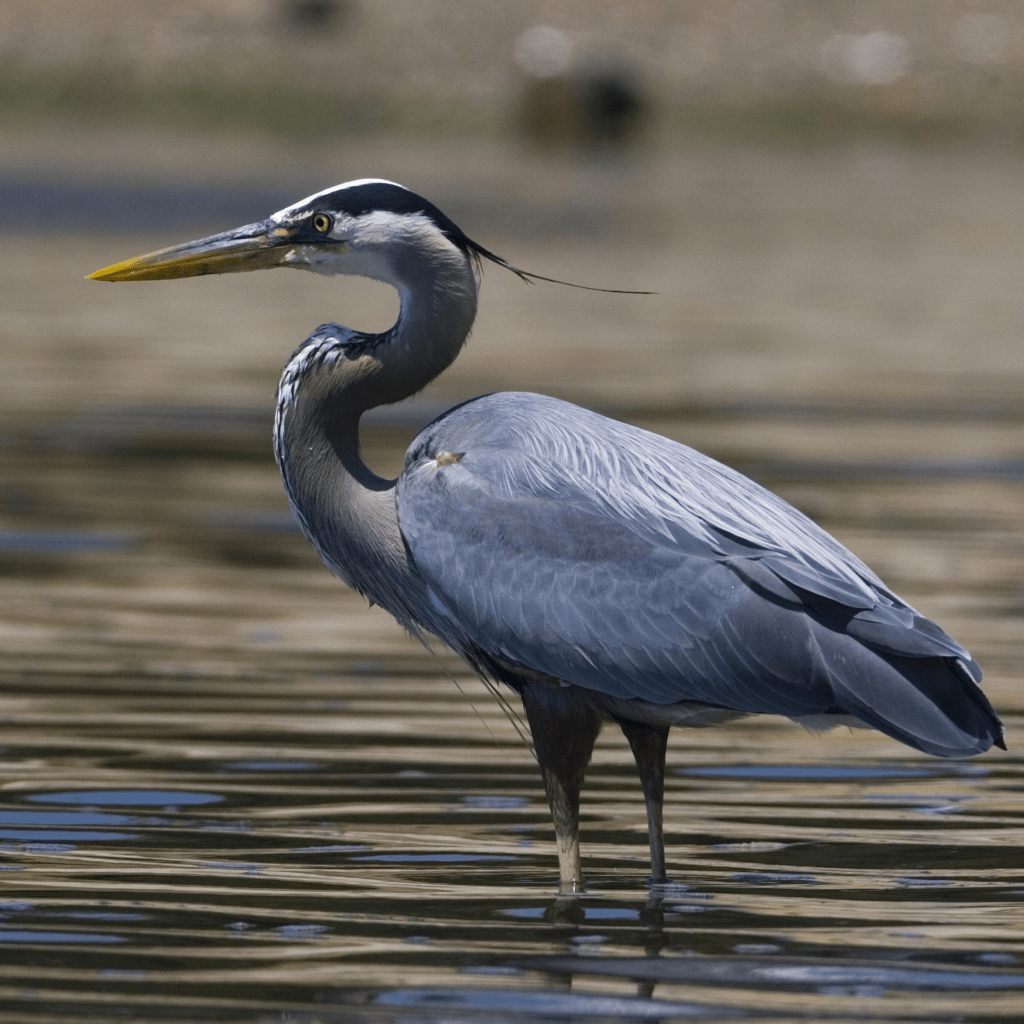

Great Blue Heron searching for its next meal

My wife, Tracy’s, Spark Bird is a Great Blue Heron, which we saw swallowing a whole large mouth bass, while it was spear fishing in Florida. Our children were with us in a canoe, paddling in Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Florida, when we spotted the bird dining, just a canoe length away from us. We sat quietly and watched the heron flip the fish around and slide it down his throat, like a large rodent in a garter snake’s mouth.

Although she has been tempted to abandon her spark bird for a Black-Necked Stilt or a Yellow-Headed Blackbird (both from fabulous sightings in Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Preserve), quickly shifted as she retold the Great Blue Heron story.

Red Breasted Nuthatch always looking for the next meal

My personal Spark Bird is the Red-Breasted Nuthatch, which I tracked by sound for several hundred yards, and faintly spotted in the branches of a few pine trees, before I positively identified it in a large Pinion Pine in El Morro, New Mexico, near Inscription Rock. The bird call of a nuthatch is distinctive and surprisingly audible, coming from this small creeper, often spotted clinging upside down while looking for bugs and just the right sap. The idea of tracking a bird by its call was foreign to me until it happened. The idea of a spark bird was planted.

What is your Spark Bird? Think through the birds you have positively spotted over the years and ask yourself a series of subsequent questions:

Which species do you keep a “mental bird list” of where you saw it last and when?

What do you like or admire about the bird?

Have you seen the bird in its breeding (most colorful) phases?

Naming your Spark Bird or birds shows the strong connections between humans and birds, which are lasting and durable. Ask most birders their spark bird and they will willingly share theirs, with avian stories of excitement and discovery.