Birds of the British Isles

Q: What are the British Isles anyway, you ask?

A: They consist of the human inhabited islands of England, Scotland, Wales, Isle of Man and Ireland.

Q: And any birds?

A: The species we spotted were the birds of late summer (August, 2025), which was problematic: We were attending a wedding in Dublin, so we made the best of our time. [Spoiler Alert!! The colorful, iconic puffins pictured above (Fratercula arctica) which seasonally nest on the cliffs of Rathlin Island, for example, had all fledged and flown the coop by the time we arrived. We had a grand time anyway, identifying some of the standard birds and some new to us species, which was exciting, nonetheless.]

We picked up a copy of Collins Complete Guide to British Birds, HarperCollins Publishers, London [1] at a local Hodges & Figgis bookstore in Dublin. All of these bird sightings were corroborated by consulting with Paul Steery’s Collins bird images and descriptions.[2] It was late summer, so we did the best we could with our time in Ireland and England to spot the birds in our local vacinity. Other than one special half-day trip via ferry to Rathlin Island from Ballycastle, County Antrim, all of the sightings were on our daily walks. Our daughter, Margaret, kept track of our daily steps and reported to us at the end of the trip that we had walked over 102 miles during our three week excursion, which seemed impressive to us.

Starting with the common species, here is our list, along with some minor commentary about the bird, the location and the impressions they left with the watcher. [3]

We spotted several of these beautiful swimmers and courtship stars. The first ones were in Hyde Park, London and the others we watched were visible through the fog on the the Straits of Moyle, between Ballycastle and Rathlin Island, Antrim County, Northern Ireland.

All over the ponds in Hyde Park, London, these stealth swimmers were fun to watch as they submerged, chased after minnows, and resurfaced many yards away from their water entry.

Although the Northern and Southern versions of this “mostly at sea” bird seem similar, from the location we saw it, the fulmars we saw were the Northern species (no dark undersides). They have what is called “light morph.” We were hard pressed to see the full extent of the sea birds, because we were so late in the breeding season, but the ones we spotted were large and glided right past us, while we watched from the bird reserve sponsored by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) on the northwest tip of Rathlin Island.

These birds were sunning themselves, wings lifted and standing on wooden poles in Hyde Park, London. They were easy to identify. We also saw them in the harbors of London, Dublin, and Ballycastle. They were all ankle-banded and well-fed.

There were about a dozen of these beautiful, dull white and black winged birds in the fields outside of Oxford, England. Their orange legs and beak are unmistakable. They seemed to be flocking on this patch of field for food, as the congregation was closely packed into about 100 meter square. We did not see any storks nesting in the towns on roofs or in trees, as we did when we were last in Northern Spain.

While we have named these heron as BLUE, they are in fact grey. They are also my wife’s Spark Bird. She loves to see them in flight, hunting for fish, or just walking among the reeds. We saw a lot of these great grey herons in Hyde Park, London, Dublin, Giant’s Causeway, Rathlin Island, pretty much everywhere. Their graceful flight patterns can still take one’s breath away.

Swans, in this case Mute, were easy to spot: on the Thames, on the ponds, on the lakes, on the rivers, even in the fields. They seem to be a signature species for England and they are extraordinarily white. Unlike the storks, these birds’ coloring is pure as the driven snow. Their orange beaks, with a prominent black knob (visible at the base of the bill, just above the black skin around the nostrils), are distinctive. And, as the name implied, they do not honk like the other swans and geese.

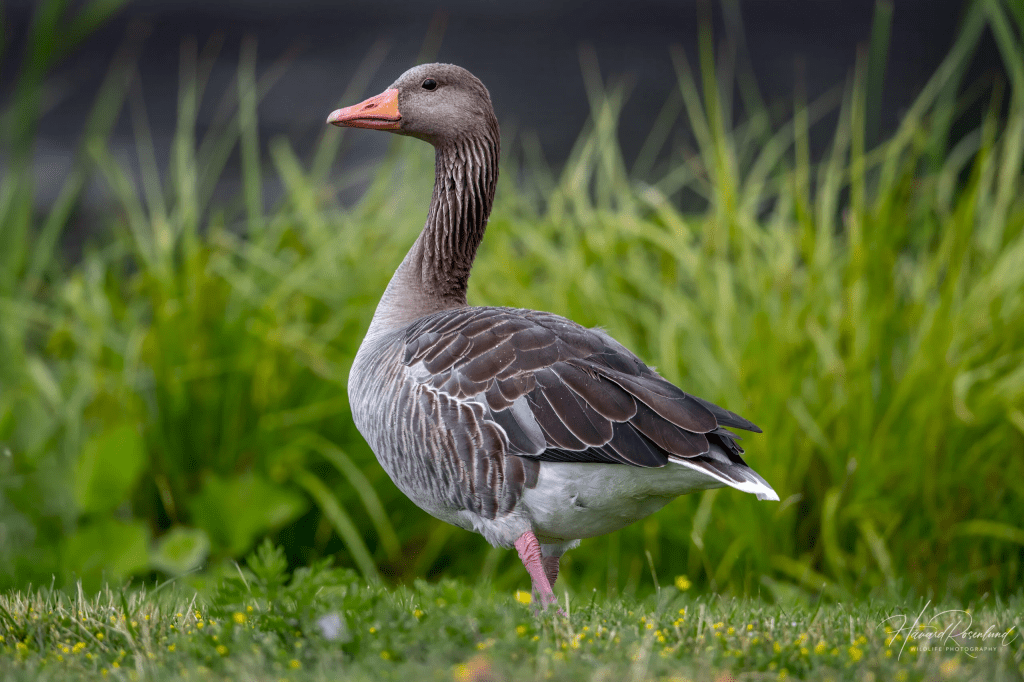

We spotted these geese when we first arrived in Hyde Park. Their poop droppings were legendary. They were munching grass and pooping peacefully, until the man with the English terrier tried, with voice commands, to control the off-leash movements of his dog. Big kerfluffle, as the pup chased the squawking gaggle into the air and off to the safety of a nearby pond. We saw these geese again at many of the parks, including Kew Gardens, which seemed to have its own plump of Greylags on the water.

The Canada Goose is one of the most distinctive large birds, whose chevron flight is a harbinger of spring and fall all over the world. The question of the actual name seems to come from the debate whether it is a Canadian goose or a Canada goose. Standard dictionaries and bird guides I’ve consulted, reflecting popular usage, list “Canada Goose” as the common name for the bird, though some of them include “Canadian goose” as a variant usage. Birders and ornithologists generally accept the popular usage when referring to the goose by its English name.

The website of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, for example, refers to the bird as “Canada goose” and describes it this way: “A familiar and widespread goose with a black head and neck, white chinstrap, light tan to cream breast and brown back.” The National Audubon Society refers to the bird online as “Canada goose,” and notes, “This big ‘Honker’ is among our best-known waterfowl.”

This particular goose looks like it was in a knock down drag out fight and has left the brawl with two black/brown bruised eyes! According to the British Waterfowl Association: “Once common along the entire Nile River valley and regarded as sacred in ancient times, the Egyptian Goose is no longer an easy bird to see in the country from which it takes its name. The species is largely confined to upper Egypt. It is, however, widespread and common throughout sub-Saharan Africa, with introduced populations firmly established in England, Holland, Belgium and France. Concerns over conflict with native species has led to restrictions on keeping them in Britain and Europe.” We saw this species in Hyde Park, Green Park, Kew Gardens and Kensington Gardens, proving it to be well represented in London.

Mallards are large ducks with what the Cornell ornithologists call a “hefty body,” which includes rounded heads, and wide / flat bills. Like many “dabbling ducks” the body is long and the tail rides high out of the water, giving a “blunt shape.” In flight their wings are broad and set back toward the rear. Mallards are a fairly large duck, noticeably larger than teal but much smaller than a Canada Goose. We saw them all over Ireland and England, as they have adapted well to the fly zones of Eur-Africa.

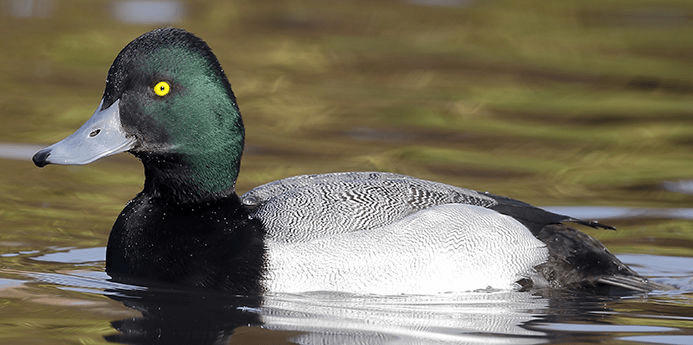

We saw the first Scaup in Hyde Park and then again floating on the Straits of Moyle north of County Antrim in Northern Ireland. The name of this water foul was originally as a “Scaup Duck” (circa 1670s). The name likely comes from (scaup or scalp) the Scottish or Northern English word for a shellfish bed, where this bird typically feeds during the winter months. Another theory on the name is that it comes from the mating call of this duck, which sounds like a percusive and seductive “scaup, scaup, scaup” according to the hens.

We spotted the Madarin Duck on our first day in Hyde Park, but only spotted the females. The males, all of whom have the spectacular feathers, must have been preening or hiding. Hiding? Hiding from what, you ask? The extraordinarily ornate male Mandarin Duck is confined as a wild species to East Asia; however, it is celebrated in art all over the continent. It is also celebrated as a symbol of love and fidelity in the land of exotic birds. Maybe hiding from the kleig lights.

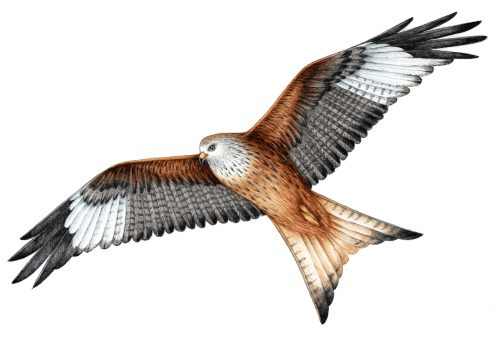

This bird flies like a kite, hence the name. It is a magnificently graceful bird of prey that is unmistakable with its reddish-brown body, angled wings and deeply forked tail. I saw it hovering over some fields, while we were on a train to the Cotswolds. This bird was saved from national extinction by one of the world’s longest-running protection programs. We are all grateful that the Red Kite has now been successfully re-introduced to England and Scotland.

Red Kites are listed under Schedule 1 of The Wildlife and Countryside Act: which means they are afforded the highest level of protection, with special penalties for offenses like disturbing the bird or its dependent young in its nest.

The common buzzard is a medium-to-large bird of prey, and their habitat and migration extends over a large range. It is a member of the Buteo genus and the Accipitridae family.

The species lives in most of Europe, and extends its breeding range across Asia to northwestern China and Mongolia. Over much of its range, it is a year-round resident. However, buzzards from the colder parts of the Northern Hemisphere typically migrate south for the winter months, landing as far away as South Africa.

The image above of an Osprey being attacked by a Bald Eagle is an interesting one, as it seems both true to life and to government policy. Although we saw neither of these fish-diet birds on the wing, it is an ironic image. The bird that the United States chose as it’s national symbol is the Bald Eagle. It may be more than a coincidence that Bald Eagles are reluctant fish divers, they are more likely to wait and watch for other birds to catch a fish. The next thing you notice is the Eagle is likely chasing the smaller osprey to drop it’s catch. The eagle, through harassment and intimidation, and sheer size, then collects the dropped spoils from the diminutive osprey. Sounds like the US national diplomacy policies (or tariffs) versus other countries, doesn’t it?

We saw them in a clutch with some young chicks huddled under bushes in the countryside outside of Oxford, England. They quickly disappeared, probably fearing we were after them with shot guns. Or perhaps they were looking for a pear tree.

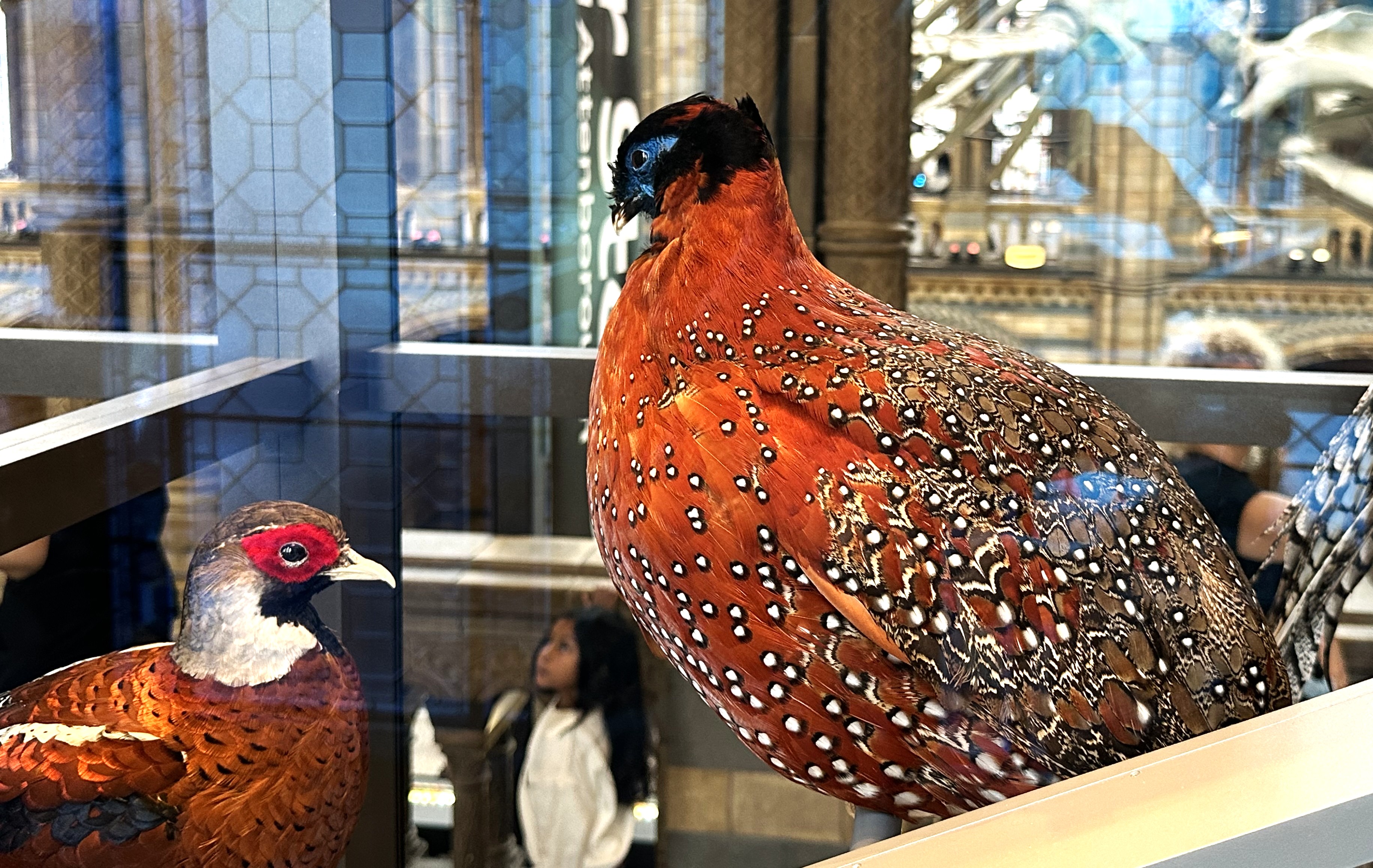

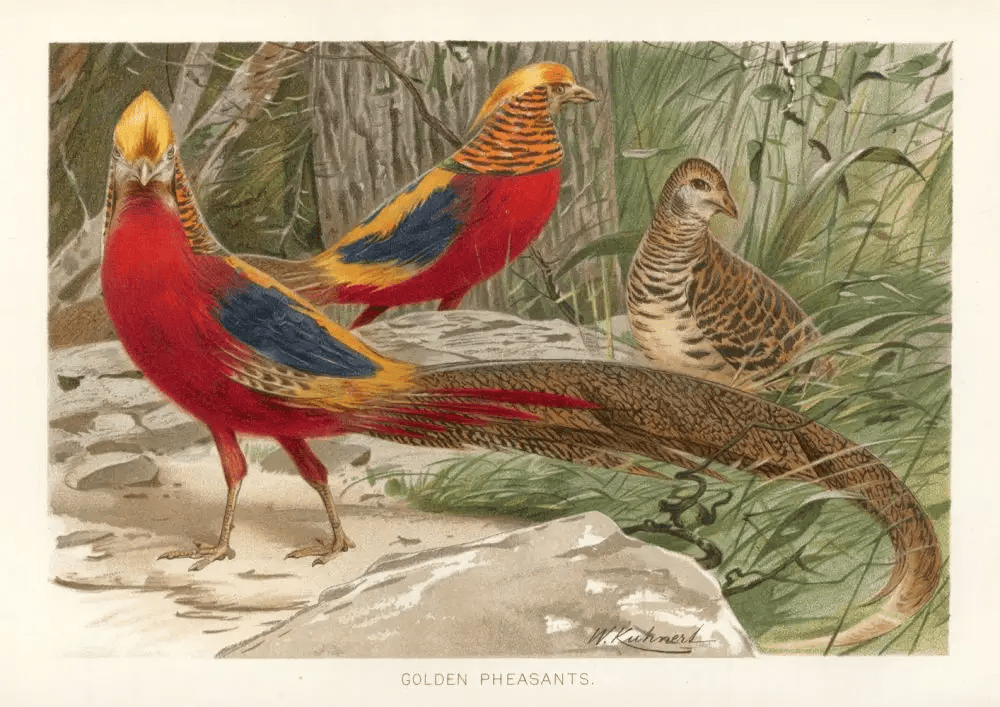

Stuffed pheasants in the Museum of Natural History, London … no we did not see these birds IRL, but in ‘taxidermied condition’ (top) and in ink by Richard Lydekker & W. Kuhnert (bottom).

We have often called these birds Gallinules, which is my American-biased understanding. When we were visiting New Zealand they were stictly called Moorhens, so it goes in the English-speaking world. We saw them in the many beautiful garden ponds around London. It is interesting to note that early every time we spotted a Moorhen, there was a Coot in the vicinity.

Note the feet on the Coot above, it has unusual webbing, which helps it with its swimming and diving in streams and lakes. The Eurasian coot is known known under several monikers: the common coot, the Eurasian coot, or the Australian coot. This water bird is a member of the rail and crake bird family. It is found in Europe, Asia, Australia, New Zealand and parts of North Africa.

The Coot has a slaty-black body, a glossy black head and a white bill with a white frontal shield. We saw it practically wherever there was standing water in England and Ireland.

The Oystercatcher, like the Killdeer, is often heard before it is seen. Oystercatchers are a group of wading birds in the Haematopodidae family, which is harder to say than to spell. We first heard and spotted them in Alaska in Glacier Bay. This time around we heard them / saw them in Ballycastle, Ireland, on our way to the ferry to Rathlin Island. They are found on coasts nearly worldwide. There are several species of this wader including the Eurasian, South Island and Magellanic birds of the species, which also breed inland.

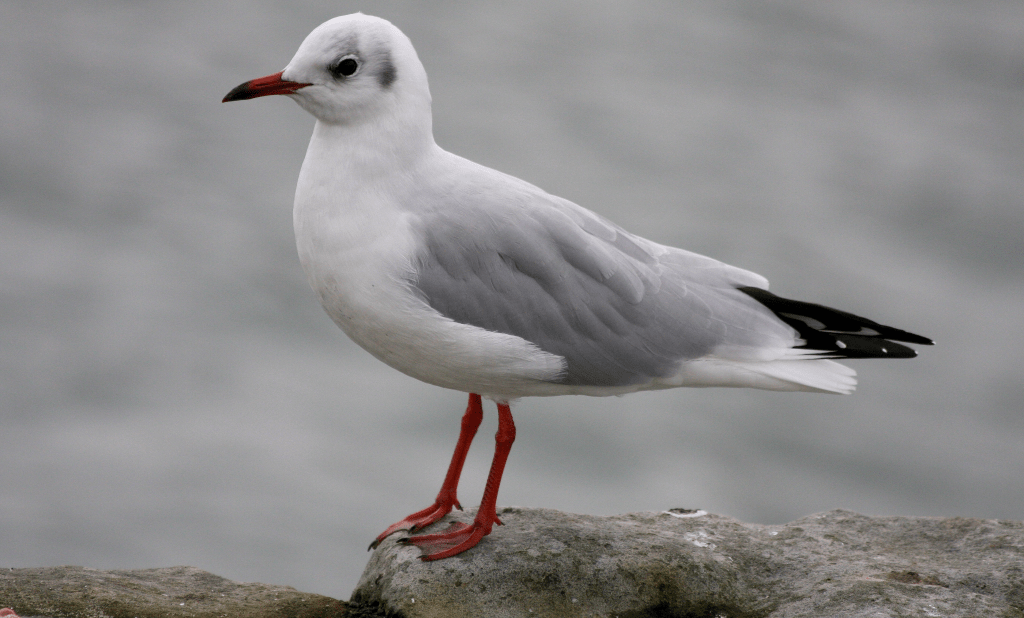

Noted for its dark head, the gull’s head is not really a black, the Black-Headed Gull’s head is more of a chocolate-brown. In fact, for much of the year, it has a white head, with some black smudges behind its eyes. It’s most commonly found almost anywhere inland. We saw them wherever there was water nearby. They are easily identified by their red legs, black-tipped red beak and seasonally brown head.

Black-Headed Gulls are known to be sociable, quarrelsome, noisy birds, usually seen in small groups or flocks, often gathering into larger parties where there is plenty of food, or when they are roosting. Sounds like some college fraternity houses I know.

For some reason, we saw these gulls in Trafalgar Square, Trinity University, Queen’s College and any site that had a bronze statue where the bird could land, stand and take a massive white dump.

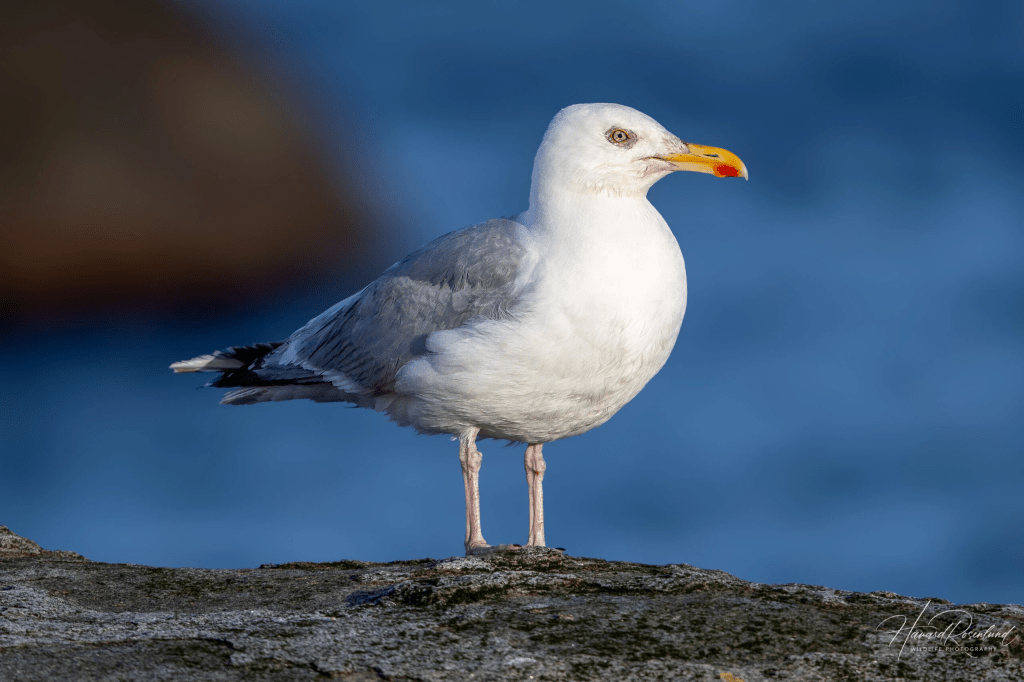

This pink legged pretty can poop with the best of them. As I understand it, the red spot on the lower beak of most gulls is to imprint on their young to peck at their mouths for feeding.

Make no mistake, these fellas are bigger and darker than their pesky, pooping fellow-gull friends. We saw them on the coast and along rivers, even in Dublin and London.

We were very late in the nesting and mating season, as stated above; however, we did identify one kittiwake roosting in the crevices along the rocks on Rathlin Island. It was pretty exciting to spot at least one nest, as weeks before there had been hundreds of them. This bird nests on seaside cliffs, often among auks and Northern Fulmars, in arctic, subarctic, and northern temperate regions. They forage over open ocean, mostly in cold waters. Note their dark black legs, as they are named in many places “Black-Legged Kittiwakes.”

Kittiwakes are known to forage while in flight by dipping or plunging into the sea, almost ternlike, to seize small fish and other prey, usually far offshore.

What shocked us most was the sheer size of the Skua, compared with the other birds that flew by, it was huge. We spotted it on Rathlin Island at the bird sanctuary sponsored by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). This large and bulky sea-lover seems more gull-like than many others. With the white on its wings and its hooked bill, there were other give-aways that we had indeed seen a Skua.

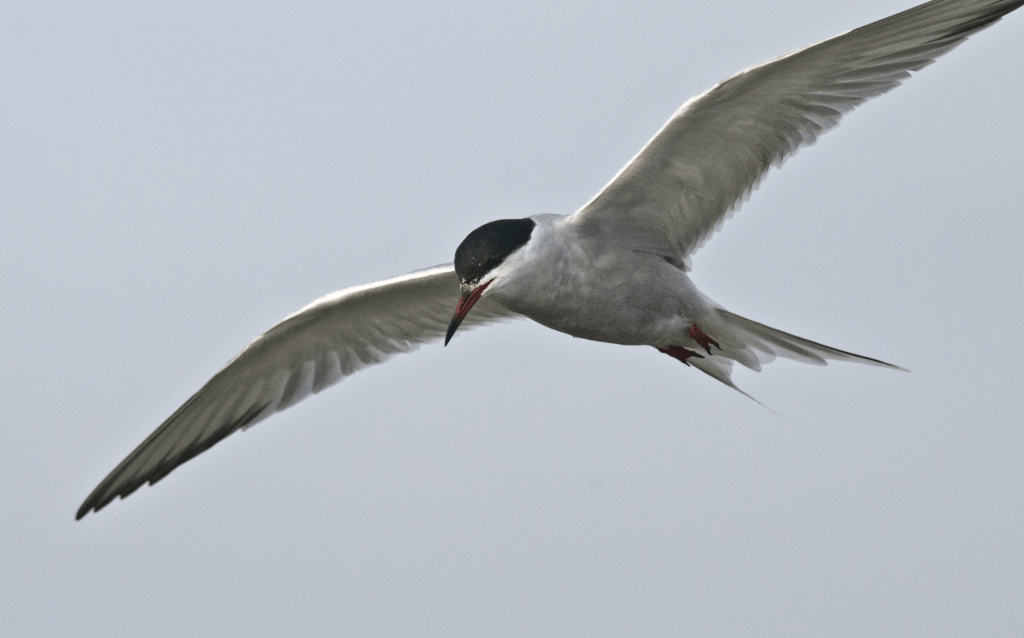

So fun to watch as they drift and pause and dive, these guys have amazing vision through to the creatures in the water below. We saw them on the Thames River in London and the River Liffey in Dublin, and many coast lines along the way. They are indeed common in the British Isles.

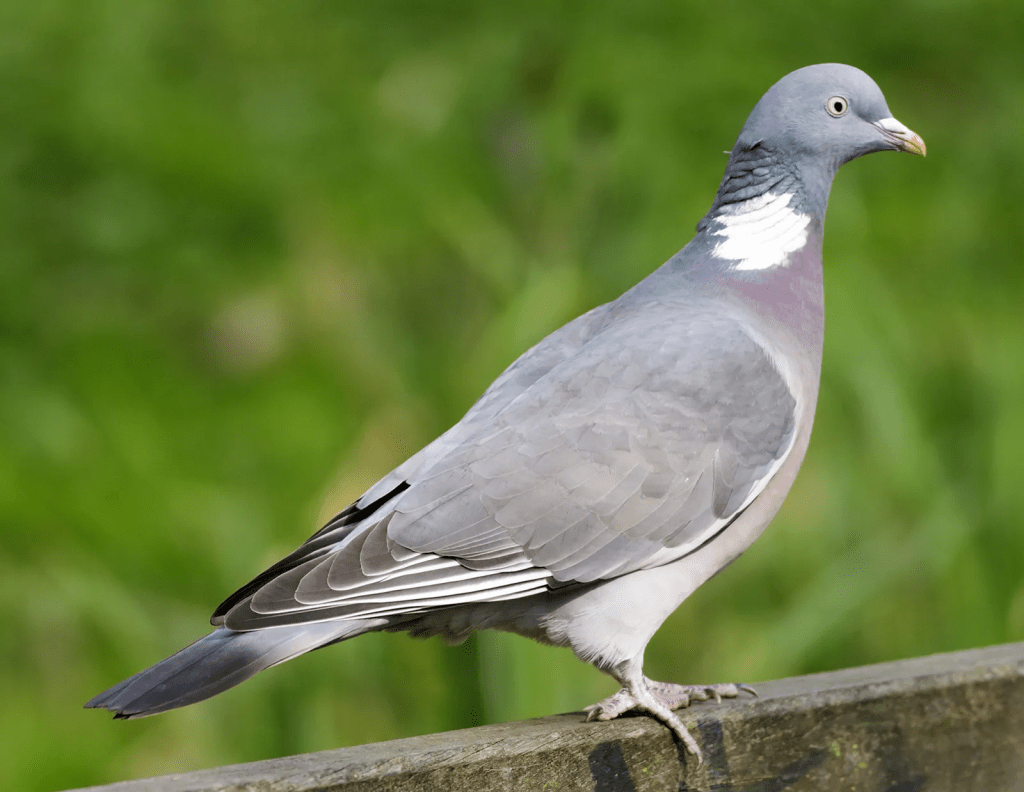

Another plump and familiar bird we spotted and heard every day was the Woodpigeon, this one was all over Hyde Park and pedestrian walkways. These birds seems much larger and louder than their pigeon and dove cousins and are about as tame as the US versions of this species. Their cooing and white neck spot are unmistakable.

Smaller than its cousin, the Woodpigeon, and a bit slimmer, these Stockdoves seemed more skiddish and not as “in your face.” We saw them in the parks at a distance. Their solitary presence seemed mostly in the fields and gardens: Kew Gardens, for example.

This species has lots of names because it is part of a ubiquitous family: Doves. The family, by the way, included pigeons. The term “feral” refers to the fact that these animals were at one time bred (i.e. domesticated) for their use as rooftop feathered food, pets and carrier pigeons, which have long since disappeared; therefore, the bird is often simply referred to as a “pigeon.”

The domesticated pigeon includes about 1,000 different breeds. Escaped domestic pigeons have increased the populations of feral pigeons around the world. Wild rock doves are pale grey with two black bars on each wing, whereas domestic and feral pigeons vary in may different colors and patterns.

The Eurasian Collared Dove, or more simply just Collared Dove, is noted for its grey head, red eye, and black stripe on its collar. This dove species is native to Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. It has also been introduced to and is thriving as far away as Japan, North and Central America, and the islands in the Caribbean. We saw it nearly everywhere pigeons would congregate, even inside Connolly Train Station in Dublin.

Active mostly in the cities near dusk, we saw the swifts in London and Dublin. A flurry of them was flying around Queen’s University in Dublin. They are beautiful fliers and are noisy, making distinctive twittering sounds (loud and shrill calls, almost like echo-location) which makes them easier to spot, when they are active chasing flying urban insects. According to researchers, this swift flies horizontally at an average speed of about 80 km/h, with peaks that may exceed 200 km/h. Doing the mental math, that means that during the typical 24 hours/day these birds may comfortably cover distances of 1,000 km and in the year approx. 360,000 km (which is 223,000 miles or 9 times around the globe annually)!

Ring-Necked Parakeet, or Pink-Necked Parakeet, as it is sometimes called, sightings were a real surprise to us, as it seems to be an exotic bird from the jungles of Central Ameria and not in an urban setting, like London. They may be a species that escaped from captivity or was released and found safe havens in the local parks. We first saw a single parakeet, when is flew at a fast pace right in front of my wife’s face, while we strolled in Kensington Gardens. We saw it again a week later in Kew Gardens, when a flock of about a dozen of them squawked their calls and flapped in unison above us. A nice surprise.

We saw swallows frequently; they all seemed to be barn swallows. We enjoyed watching them at Luttrellstown Castle outside Dublin and again at the Giants’ Causeway in County Antrim, Ireland, where we had time to walk alongside the cows, the sheep, and the bugs. The flying bugs of early August were hatching in wild profusion, so there was plenty of fuel for these birds to feast upon, and lots of swatting by us. Thank goodness the bugs were only annoying and not biting.

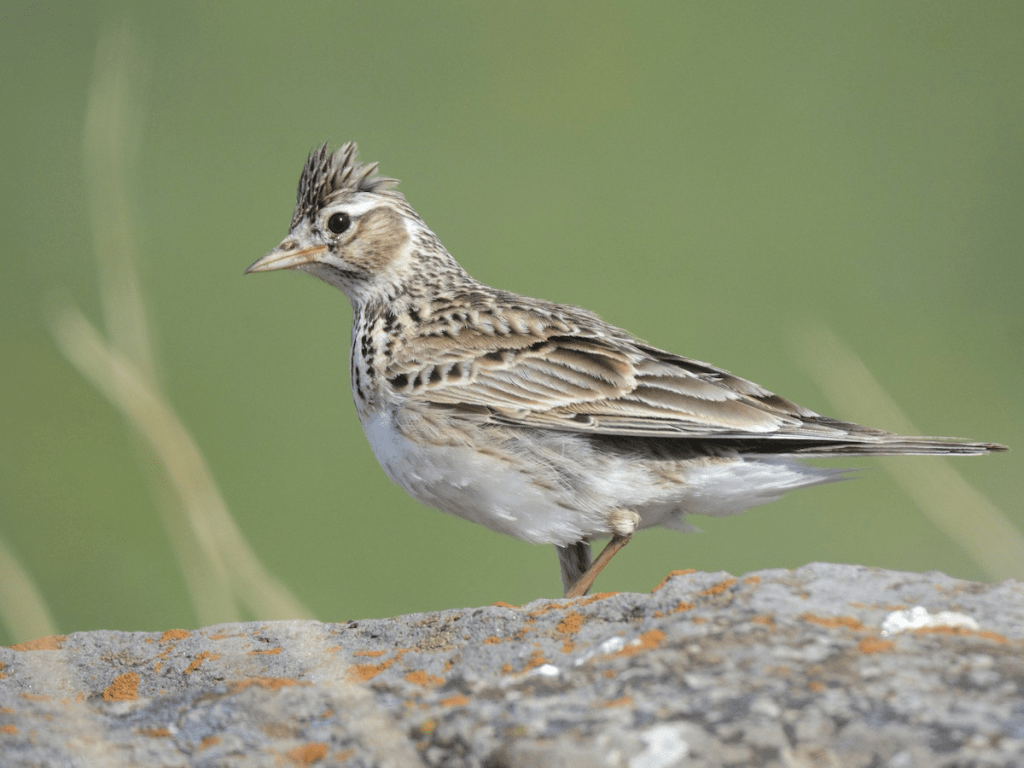

We saw the Skylark hopping ahead of us on the trails in the Cotwolds of England and the trails of Antrim, Ireland. They were mostly muted colors, like sparrows, and seemed particularly good at hopping on insects on the ground, rather than nabbing them out of the air (or sky) as their name seems to indicate.

Of the two Wagtails in this post, I had a hard time distinguishing them from eachother. We watched them in Belfast and then again for a long time on the Giants’ Causeway in Antrim, Ireland. Their tails bobbed up and down and these birds competed with each other for the juciest of worms on the grass above the Causeway Visitor’s Center. The ones we spotted had the black eye-stripe, but the app I used said they were Pied Wagtails. Since I am not sure which of the species we saw, I have posted both of these birds.

The White Wagtail is known for its long, continuously waggng tail, and bold black, white and grey plumage. They are, however, more rare. The exact coloration of the bird seems to vary across its breeding range, which extends to North Africa. This insect loving bird is most often found in open habitats like wetlands, farmland, and urban areas. According to one source, “the Motacilla alba alba is the nominate subspecies of the breed.”

The Pied Wagtail is pictured for comparison to the White Wagtail above, as the immatures and females of the species are hard to distinguish for amateur birdwatchers, like us. The more I look at these wagtail images, I think we were watching the Pied yarrellii sub-species.

While walking along the Giants’ Causeway, we heard, but did not see the tiny wrens. They were there, but hiding in the briars along the hillside. It was raining off and on, and the crowds were prolific, so we did not have time to stop and make positive visual identification. But we heard the wren, no doubt, which are wonderfully melodic, even during inclement weather. I have always been struck by the Latin name of the wren, as if they are from another world, the realm of troglodytes, which seems fitting with the myths and tales of Finn mac Cumhaill and Benandonner, his Scottish rival, on this UNESCO World Heritage site in Ireland.

The Waxwing, in this case the garrulous Bohemian version, can be heard as they congregate and forage for berries. We heard and saw them first in Hyde Park, London. The Waxwing has a moveable crest of feathers on its head. The feathers are mainly gray-brown. There is a thin black stripe through the eye with a white stripe below it. The tail has a yellow tip. The wings include some yellow, white and red markings. The feathers below the tail are orange-red. This species eats insects, fruits and berries. Bohemian waxwings are often seen in cities and towns where they feed on the fruits of ornamental trees. We also saw and heard them in the Cotswolds, west of London.

Contrary to nursery rhymes, I have never known blackbirds to be baked in a pie. That said, these are genuinely curious birds, whose yellow eye ring and beak are remarkable. When they stand still, the yellow pops out at the viewer. We spotted a few Blackbirds on the first day in England, when we were strolling in Hyde Park, London, and again in Kew Gardens. They were having the best time, as were we.

We heard a great racket of noise, all coming from a patch of willows on the streams around Upper Slaughter in the Cotswolds of England. Going closer for a view, it was their sound, rather than their color that I noticed. These warblers are perhaps best identified by their voices: their song is pleasant, a slightly descending warble. I thought it might be a yellow warbler or a chiffchaff. These Willow Warblers were found in a wooded habitats, from mixed forest to willow thickets in open country.

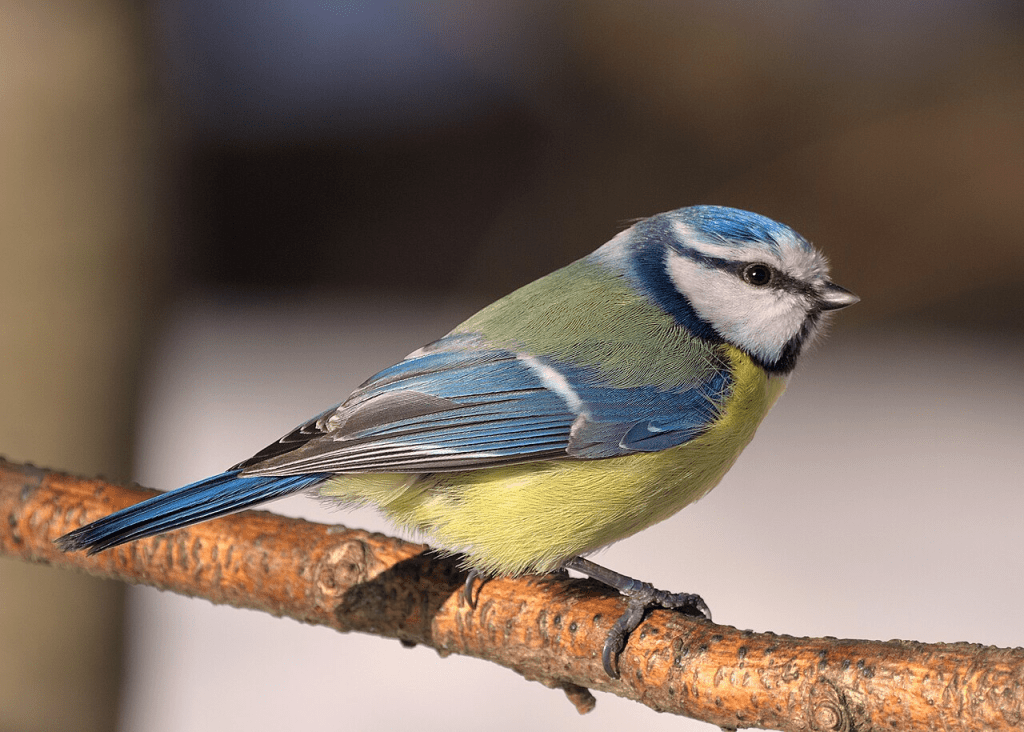

On our first day in London, we spent a glorious day strolling in Hyde Park. Quite close to our hotel, we were able to take our time, recover from Jet Lag, and see some wildlife. The first birds we heard were what sounded like the Black-Capped Chickadees we have in Oregon. On closer inspection they were Tits. We saw several species of Tit those early days, varying in size and habitat. They are pictured below.

Tits, or Titmice, are common and widespread across the British Isles and the rest of Europe. We saw them in Hyde Park and Kew Gardens, London, and Trinity University in Dublin. They are fascinating little creatures that seem to have been part of Britain’s avian population for thousands of years. The name “caeruleus” means “blue” in Latin, describing the blue coloration of the bird’s plumage.

Beyond its charming appearance and cheerful songs, blue tits hold a special place in British folklore and natural history. Seeing a blue tit is often associated with various meanings: cheerfulness and joy; resourcefulness and adaptability; hope and optimism. Each one of these interpretations of sighting a Tit is uplifting, so dig into the folk lore and see what appeals to you. There are also various Latin names for these birds, so I have included the ones I have found, not being sure which is definitive.

Stunningly beautiful in its own right, the Starling, or Eurasian Starling, has nearly taken over the world. Not only is it prolific in the British Isles, it is also a scourge on North America. An invasive, non-native species to the US, Starling were introduced by the Schieffelin family to New York City’s Central Park in the late 19th century. They now are numbering in the millions. They are known for outcompeting native cavity-nesting birds for nest sites, causing damage to crops, and spreading diseases, leading to the recommendation to control their populations.

Starling are also known for their curious flight patterns, or murmurations, which take up the evening sky, like a modern day drone exhibition.

We saw this loud bird in Hyde Park and just about every other park after that sighting. The coloration and long tail are fun to watch, particularly in flight. Magpie are among the few avians whose tail is longer than its torso. [Everywhere in the world we have seen these birds, there is a trash pile nearby. They seem to be attracted to the sight and smell of human garbage.] In the US there are black and yellow billed species. There seems to be only the black billed version in the British Isles.

Growing up in Baltimore Maryland: let me introduce Edgar, Allen, and Poe!!! Go, Ravens.

We saw this variation of the crow in Luttrellstown, Ireland, when we went to the Castle for the wedding. The Hooded Crow we saw looked less scruffy than the image I found of this species.

Aptly named, this is one of the most fierce home fighters I know. In the US the House Sparrow, like the Starling, harasses the other birds to go somewhere else to feed and nest. It is just nasty to other birds.

The Collins Guide had an entire section of birds listed as “out of the ordinary species.” Unfortunately, we saw none of them.

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=

References:

[1] Sterry, Paul – writer/editor, Collins Complete Guide to British Birds, HarperCollins Publishers, London, 2004. As pronounced on the book’s cover, BBC Wildlife claims this collection of avian creatures is “everything a birdwatcher needs to know in one easy-to-use portable guide.”

[2] Some of the Latin names of the birds I researched may have been modified over the years. The Tits, for example, seem to have different Latin names since I looked them up in the Collins Guide.

[3] Please note: except for a few personal photos, these images were captured and copied from public sources on the internet. When the photographer is known, I have attempted to include their names with the image.