Birds of Say

The proper name “Say” has been identified with many bird and animal species. These monikers refers to Thomas Say, an admired American naturalist and entomologist in his day, for whom Say’s Phoebe (Sayornis saya) and other animals were named. There are at least two other birds named after Thomas Say as requested by scientific admirers: the Black Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans) and the Orange-crowned warbler (Vermivora celata).[1]

Who is Thomas Say?

Born in Philadelphia into a prominent Quaker family, Thomas Say was the great-grandson of John Bartram, and the great-nephew of William Bartram. His father, Dr. Benjamin Say, was brother-in-law to another Bartram son, Moses Bartram. The Say family owned a house known as “The Cliffs” at Gray’s Ferry, which was adjoining the Bartram family farms in Kingessing township, Philadelphia County. As a boy, Say often visited the family garden, Bartram’s Garden, where he frequently took butterfly and beetle specimens to his great-uncle William Bartram. Beyond his Bartram connections, Say is credited with some remarkable work on his own

Say is described in records as: An early 19th Century American explorer, entomologist, conchologist, herpetologist, zoologist, pharmacist, herbalist and naturalist. (Note: that although some of these descriptions are redundant, that is 8 different areas of expertise!) In 1820, he was the chief zoologist on an expedition to the Rocky Mountains led by Stephen Harriman Long. On that trip and other expeditions he is credited with writing and documenting the first descriptions of many animal species, and the Sayornis genus of phoebe birds was named in his honor.

Thomas Say’s studies of insects, birds, reptiles and shells, included thorough writing on many topics. He is credited with numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Georgia, the Rocky Mountains, Mexico, and elsewhere. These expeditions made him an internationally known and admired naturalist. Say has been called the “Father of American descriptive entomology and American conchology,” which is quite a mouthful. He served as librarian for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, curator at the American Philosophical Society (elected in 1817), and he served as a professor of natural history at the University of Pennsylvania in 1822.

Thomas Say’s Career

Say trained to be an apothecary and herbalist, leading to his interest in being a pharmacist. A self-taught naturalist, Say helped found the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP) in 1812. In 1816, he met Charles Alexandre Lesueur, a French naturalist, malacologist (study of conch shells), and ichthyologist (study of fish species) who soon became a member of the Academy and served as its curator until 1824.

At the Academy, Say began his work on what would eventually be publish as American Entomology. To collect insects, he made numerous expeditions to frontier areas, risking American Indian attacks and weather hazards of traveling in wild countryside. In 1818, Say accompanied his friend William Maclure, then the ANSP president and father of American geology; Gerhard Troost, a geologist; and other members of the Academy on a geological expedition to islands in the Atlantic, off-shore of Georgia and Florida. The islands were then a Spanish colony and not yet part of the US.

In 1819–20, Major Stephen Harriman Long led an exploration to the Rocky Mountains and the tributaries of the Missouri River, with Say accompanying the group as zoologist. Their official account of this expedition included the first descriptions of the coyote, swift fox, western kingbird, band-tailed pigeon, rock wren, Say’s phoebe, lesser goldfinch, lark sparrow, lazuli bunting, orange-crowned warbler, checkered whiptail lizard, collared lizard, ground skink, western rat snake, and western ribbon snake.

In 1823, Say served as chief zoologist in Maj. Stephen Long’s expedition to the headwaters of the Mississippi River. He traveled on the “Boatload of Knowledge” to the New Harmony Settlement in Indiana (1826–34), a utopian society experiment founded by Robert Owen. Say was accompanied by Maclure, Lesueur, Troost, and Francis Neef, an innovative pedagogue. There he later met Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz, another naturalist.

On January 4, 1827, Say secretly married Lucy Way Sistare, whom he had met as one of the passengers to the new settlement of New Harmony, Indiana. She was a highly regarded artist and illustrator of specimens, as in her illustrated book American Conchology. Lucy was the first woman to elected to the Academy of Natural Sciences, which formally recognized her scientific contributions and achievements in 1868.

At New Harmony, Thomas Say carried on his monumental work describing insects and mollusks, leading to his completion of two classic works:

- American Entomology, or Descriptions of the Insects of North America, 3 volumes, Philadelphia, 1824–1828.

- American Conchology, or Descriptions of the Shells of North America Illustrated From Coloured Figures From Original Drawings Executed from Nature, Parts 1–6, New Harmony, 1830–1834; Part 7, Philadelphia, 1836.

Many of the scientific names assigned by Say are no longer accepted by the Academy. Lists of the former names matched with current scientific and common names are available from other sources.

During their years in New Harmony, the Say family experienced considerable difficulties. Say was a modest and unassuming man, who lived frugally like a hermit. He abandoned commercial activities and completely devoted himself to his studies, making “normal life” difficult for his family. Lucy Way Sistare Say outlived her husband by 52 years.

Thomas Say died, apparently from typhoid fever infections, in New Harmony, Indiana, on October 10, 1834. He was 47 years old. His wife, Lucy Say, returned to New York after his death and remained active in art and science. She died in 1886, at the age of 86.

Say’s Legacy and Honors

Say described more than 1,000 new species of beetles, more than 400 species of insects of other orders, and seven well-known species of snakes.

Other zoologists honored him by naming several taxa after him:

- Dyspanopeus sayi (S. I. Smith, 1869) – Say’s mud crab

- Portunus sayi (Gibbes, 1850) – a swimming crab of the family Portunidae

- Porcellana sayana (Leach, 1820) – an Atlantic porcelain crab

- Lanceola sayana (Bovallius, 1885) – an amphipod from the family Lanceolidae

- Calliostoma sayanum (Dall, 1889) – a sea snail in the family Calliostomatidae

- Diodora sayi (Dall, 1899) – a sea snail in the family Fissurellidae

- Oliva sayana (Ravenel, 1834) – a sea snail in the family Olividae

- Sayella (Dall, 1885) – a genus of sea snails in the family Pyramidellidae

- Propeamussium sayanum (Dall, 1886) – a saltwater clam in the family Propeamussiidae

- Appalachina sayana (Pilsbry in Pilsbry & Ferriss, 1906) – a land snail in the family Polygyridae

- Pituophis catenifer sayi (Schlegel, 1837) – the bullsnake

- Sayornis (Bonaparte, 1854) – a genus in the tyrant flycatcher family

- Sciurus niger rufiventer – Say’s squirrel

- Chlorochroa sayi (Stål, 1872) – Say’s stink bug, a species of stink bug

Birds named after Thomas Say

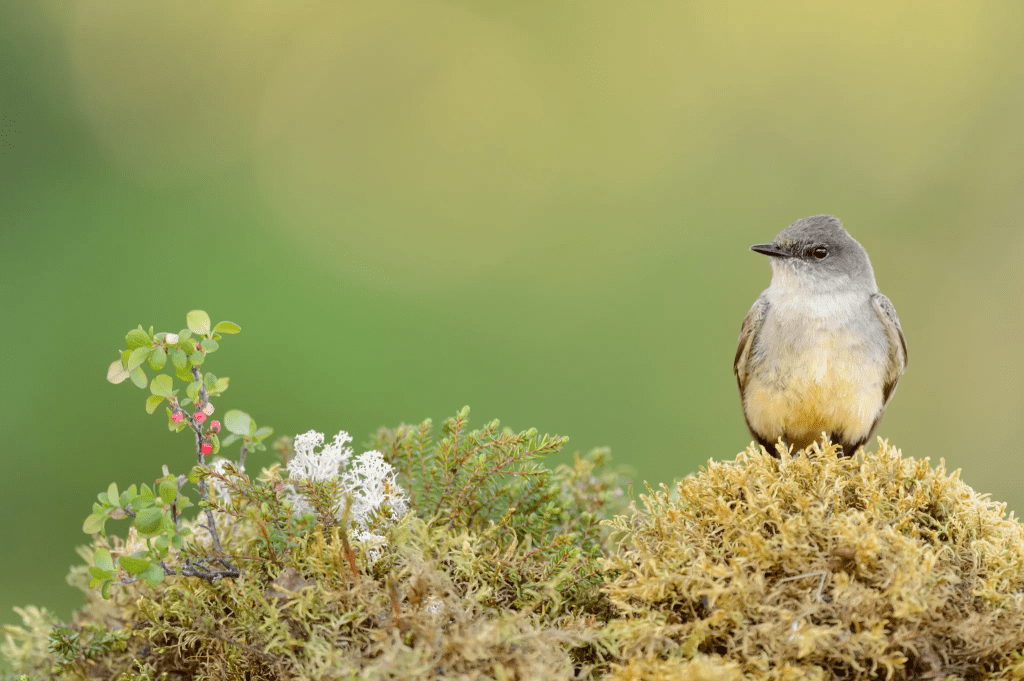

- Say’s Phoebe (Sayornis saya): This bird was named by Charles Bonaparte after Say encountered it in 1819.

- Black Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans): This bird is from the same genus as Say’s Phoebe and was also named in honor of Thomas Say.

- Orange-crowned warbler (Vermivora celata): This bird also has a name associated with Thomas Say.

- Fringilla psaltria: While it’s not a common name, Say named this bird, which was later reclassified.

What’s in a Name? The Fate of Say’s Phoebe Moniker?

Say’s Phoebe is one of 150 or so eponymously named birds in the classic bird books and life-lists we all research, curate, and cherish.

PLEASE NOTE: the American Ornithological Society has stated that it will soon rename ALL of these species. While Say’s name has long been attached to many bird and animal species, other names, such as Western Bridge-Pewee, Rocky Mountain Pewee, and Desert Phoebe, drop the longtime name and hint at the species’ western range and habitat preference.

One Colorado birder suggested the name be changed to Sunrise Phoebe as a replacement for the Say’s name. This descriptive name captures the hint of glowing, rusty orange found on the species’ stomach and flanks. And they think it’s this quality of the Say’s Phoebes that makes them such a welcome winter visitors. When they arrive, they warm the world. Or at least they remind us of warmer times ahead.

References:

[1] The bulk of this post is from the Wiki pages created by others to describe Thomas Say. The primary site is: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Say