Birds: Flamingo

There is a collection of homeowners in SW Portland, Oregon, who love flamingos. Not the live ones exactly. They seem to love the plastic versions which are displayed on their fences, planted in their gardens, and pointing to their flower pots. Why these Oregonians gravitate to this aviary is a mystery. As strange as it is for those in the Northwest to see these shorebirds, it is even stranger to see them covered in snow and ice.

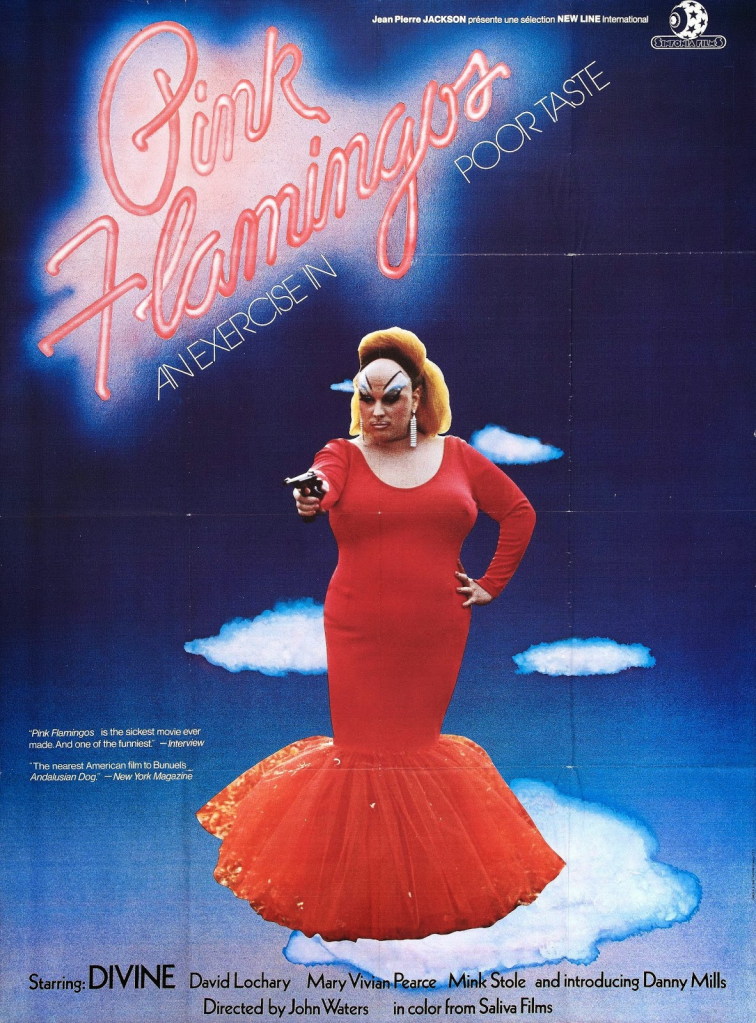

That said, having grown up in Baltimore and watched the John Waters budget movie, Pink Flamingos, an Exercise in Poor Taste, starring Divine and produced by Saliva Films, it should not seem too unusual. [2] After all there are lots of bird icons that have lives of their own beyond the flying creatures: think of Edgar, Allen, and Poe, the Ravens’ Mascots, and Woody the Woodpecker cartoons.

Yet, these beautiful creatures are otherworldly. Look at their colors, their beaks, their legs, their mating habits, their hanging on to life in this strange planet.

American Flamingo: the Survival Story of an endangered species …

American Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber)

One of the Caribbean’s greatest conservation success stories began in the early 1950’s. Ornithologist Robert Porter Allen, Audubon’s first director of research, arrived in the Bahamas’ southernmost islands to discover only a scant hundred or so flamingos — one of the last remaining breeding colonies of American Flamingo on earth. Thanks to the efforts of Allen, the Audubon Society, Morton Salt, and others, the Bahamian government preserved roughly half of the island of Great Inagua as a National Park. The island’s flamingo population blossomed in the decades since and now tops 80,000 — outnumbering human residents on Great Inagua by more than 80 to 1.

What is Different About Flamingos? [1]

In the shallow, salty waters of Lake Rosa in Inagua National Park, adult flamingos herd chicks into groups called crèches. Just a few babysitting adults supervise each crèche while other parents forage, returning periodically to feed their own young, which they recognize by vocal patterns and appearance. Flamingos lay only a single egg each year; if it is lost or damaged, they do not typically lay a replacement egg. Both the male and female gather mud with their beaks, then shape the nest with their feet. Flamingos are social birds; they often build nests close together, creating flamingo neighborhoods.

But those chicks that stray from the crèches are vulnerable to predators. Adults feed their chicks a secretion of the upper digestive tract referred to as flamingo “milk,” much like doves and pigeons provide. The secretion is caused by the hormone prolactin, which both male and female flamingos produce. Chicks must be fed by adults for about three months, until their short, straight bills gradually lengthen and curve downward enough for them to begin picking up food on their own. Once a chick can forage, it is effectively weaned, and the parents no longer provide for it.

The Morton Salt Company is Inagua’s biggest employer. Audubon Society members have helped train guides for a bird-based ecotourism program on Great Inagua that aims to diversify islanders’ income. Guides now earn part of their living by showing visitors Inagua’s flamingos and other birds. “Our ancestors were in the business of hunting the flamingos,” one guide says. “Now our generation is in the business of protecting them.”

A Morton Salt Company railroad track creates a hill of salt drawn out of ocean water through natural evaporation. Though development and habitat loss threaten flamingos in much of their range, Morton’s salt-concentrating ponds provide valuable shallow-water habitat for Great Inaguas’ birds.

Salty foam, which forms on water when organic matter churns up, blows across a road that runs between Morton’s ponds. Brine shrimp eat algae that grows at the bottom of the ponds, and the flamingos eat the brine shrimp, which helps the process of concentrating salt—creating a symbiotic relationship.

Born a drab gray or white, the flashy waders derive their brilliant mature plumage from red-orange pigments found in their steady diet of crustaceans, larvae, and algae.

Even John Waters would cheer this survival story on … as an exercise in great taste.

References:

[1] the idea for this bird post started with an Audubon Magazine article about Robert Porter Allen.

[2] the ideas in John Waters’ head are anyone’s guesses.