Birds of America: J.J. Audubon

The bird population in the US has several species named after J.J. Audubon: Audubon’s shearwater, Audubon’s warbler and Audubon’s oriole, for example. Many bird names are on the chopping block in 2024-2025 because of an upheaval in the American Ornithological Society. The impending changes are due to more than simple naming conventions.

More Than Birds

The Audubon Society faces a backlash after deciding to keep its name which, according to publications “evokes a racist enslaver.” John J. Audubon may have inspired generations of birders with his Birds of America compendium, but his legacy also includes racist views. He is now known to have owned and sold enslaved people, which is bringing calls for the National Audubon Society to change its name.

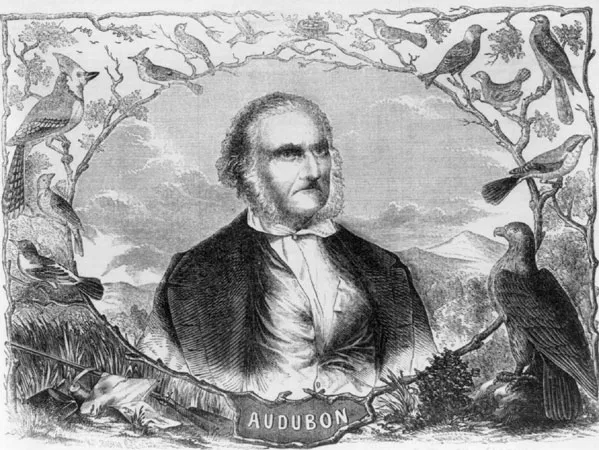

John James Audubon (1785-1851)

J.J. Audubon: Genius or Fraud?

John James Audubon (1785-1851) was not the first person to attempt to paint and describe all the birds of America (Alexander Wilson has that distinction), but for half a century he was the young country’s dominant wildlife artist. His seminal elephant folio The Birds of America, a collection of 435 life-size prints, quickly eclipsed Wilson’s work and it is still a standard against which 20th and 21st century bird artists, such as Roger Tory Peterson and David Allen Sibley, are measured.

It’s fair to describe John James Audubon as a genius, and a pioneer. His contributions to ornithology, art, and culture are enormous. At the same time he was a fabulist. More specifically he is now known as someone whose actions reflected a dominant white man’s view in his pursuit of scientific knowledge, and he was a complex and troubling character who did despicable things even by the standards of his day. He was contemporaneously and posthumously accused of both academic fraud and plagiarism. But far worse, he enslaved Black people and wrote critically about emancipation. He was accused of stealing human remains and sending the skulls of those he disinterred to a colleague who used them to assert that whites were superior to non-whites.

Complicating this history is his ambiguous background: Some researchers have credibly argued that Audubon was born to a woman of mixed race, which would mean that the most famous American bird artist was a man of color. Others insist that Audubon’s mother was white. Audubon himself lied about the circumstances of his birth, claiming to have been born in Louisiana. Whatever his circumstances of his birth, his beliefs and actions speak for themselves.

The Origin of the Audubon Society

Audubon died decades before the first Audubon societies were founded, so how did National Audubon Society come to bear his name? A naturalist named George Bird Grinnell, one of the founders of the early Audubon Society in the late 1800s, was tutored by Lucy Bakewell Audubon, John James Audubon’s widow. Grinnell chose the society’s name because of Audubon’s stature in the world of wildlife art and natural history. The Audubon name was honored and venerated by the Society for the next 170 years.[3]

Audubon: Early Years

John James Audubon was born in Saint Domingue (now Haiti) in 1785, the illegitimate son of a French sea captain and sugar plantation owner. The identity of his mother is in dispute; she could have been a French chambermaid named Jeanne Rabine, but there is compelling evidence that she was a mixed-race housekeeper named Catherine “Sanitte” Bouffard. At the age of five — which coincided with the beginnings of the Haitian Revolution — Audubon was sent to Nantes, France, and was raised by his father’s wife, Anne. There, John James Audubon took an interest in birds, nature, drawing and music.

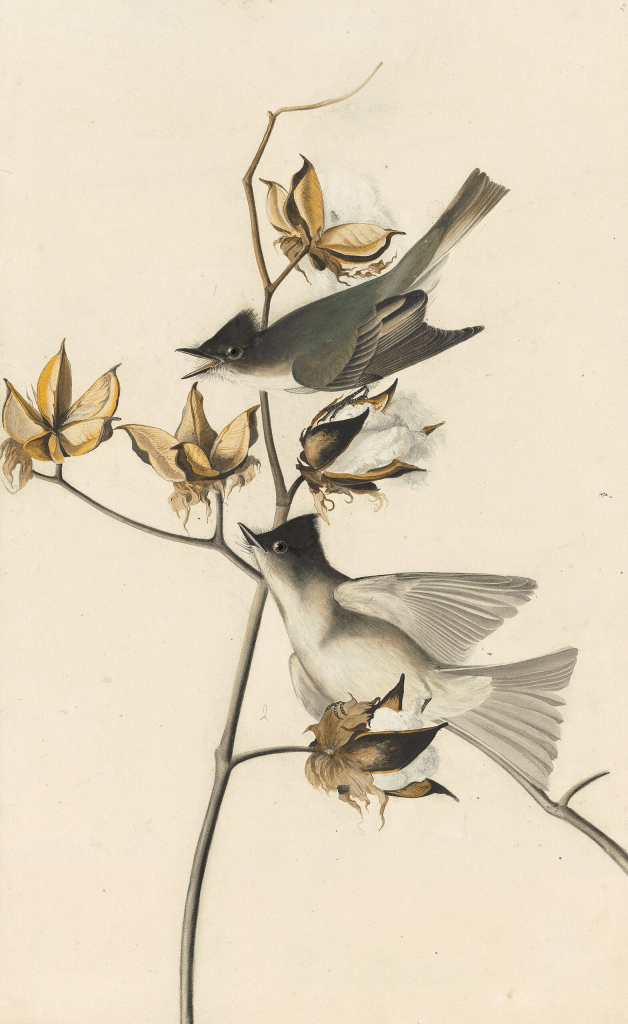

In 1803, at the age of 18, he was sent by his family to America, in part to escape conscription into Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s army. Audubon lived on the family-owned estate at Mill Grove, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, where he hunted, studied and drew birds. It was there that he met his wife, Lucy Bakewell. While living in Mill Grove, he conducted the first known bird-banding experiment in North America, tying strings around the legs of Eastern Phoebes; he learned that the birds returned to the very same nesting sites each year.

Audubon Octavo Print – Pewee Flycatcher / Eastern Phoebe – Plate 63 – 3rd Edition

Audubon spent more than a decade as a businessman, traveling down the Ohio River to western Kentucky — then the beginning of the western frontier — and setting up a dry-goods store in Henderson. He continued to draw birds as a hobby, amassing an impressive portfolio. He also bought and sold enslaved people during this time to support his venture. Audubon was successful in business for a while, but hard times hit, and in 1819 he was briefly jailed for bankruptcy.

With no other prospects, in the early 1820s Audubon set off to depict America’s avifauna, with nothing but his gun, artist’s materials, and a young assistant. In 1826, he sailed with his partly finished collection to England, where his life-size, highly dramatic bird portraits, along with his embellished descriptions of wilderness life, hit just the right note at the height of the Continent’s Romantic era. Audubon found a printer for The Birds of America, first in Edinburgh, then London, and later collaborated with the Scottish ornithologist William MacGillivray on the ornithological biographies — life histories of each of the species in the work.

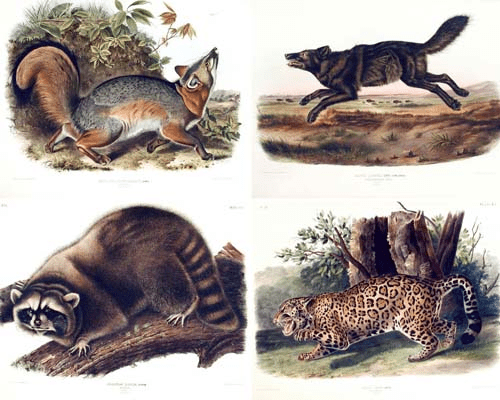

The last print was issued in 1838, by which time Audubon had achieved fame and a modest degree of comfort, traveled the country several more times in search of birds. He eventually settled in New York City. He made one more trip out West in 1843, the basis for his final work of mammals, the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, which was largely completed by his sons and the text of which was written by his long-time friend, the Lutheran pastor, John Bachman (another anti-abolitionist whose daughters married Audubon’s sons).

The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

Audubon died at age 65. He is buried in the Trinity Cemetery at 155th Street and Broadway in New York City. [1]

Birds depicted throughout Audubon’s Birds of America reflect the once-common practice of naming flora, fauna, and landscape features for the person who “discovered” them. The record of this in Birds of America stands to remind us of the colonialism, racism, and violence that marked the period during which Audubon was collecting and drawing American birds.

While the majority of birds in his books are named with descriptive language that helps identify them (information about their behaviors, as in Hermit Warbler; or about their plumage, as in Black Throated Gray Warbler), some carry the names of slave owners, anti-abolitionists, Confederate generals, U.S. Calvary officers associated with the genocide of indigenous peoples, and “scientists” whose work is now understood to be disreputable, damaging, or spurious.

A growing number of scientists and naturalists now advocate for replacing so-called eponymous bird names with descriptive alternatives. Many recommend the removal of all eponymous bird names, regardless of the character or qualities of the individuals for whom birds were named. A comprehensive change, they argue, honors wildlife and natural history over human endeavor and the will to dominate the natural world.

It’s especially hard for me to imagine calling certain birds, such as Cooper’s Hawks and Swainson’s Hawks, for example, by another name. That said there’s a long list of other birds that I see regularly or occasionally whose biologist’s names would likely be changed, including the following:

- Bullock’s Oriole

- Cassein’s Finch

- Clark’s Grebe

- Clark’s Nutcracker

- Cooper’s Hawk

- Gambel’s Quail

- Lewis’s Woodpecker

- Lincoln’s Sparrow

- MacGillivray’s Warbler

- Say’s Phoebe

- Steller’s Jay

- Swainson’s Hawk

- Townsend’s Solitaire

- Williamson’s Sapsucker

- Wilson’s Phalarope

- Wilson’s Snipe

- Wilson’s Warbler

- Woodhouse’s Scrub Jay

More about the movement to change bird names: What’s in A Name? – reading and resources. [2]

[1] https://johnjames.audubon.org/john-james-audubon-0

[2] https://beineckeaudubon.yale.edu/whats-name-reading-and-resources

[3] https://www.nypl.org/events/exhibitions/galleries/explorations/item/4094