Powell’s Pals: O.C. Marsh

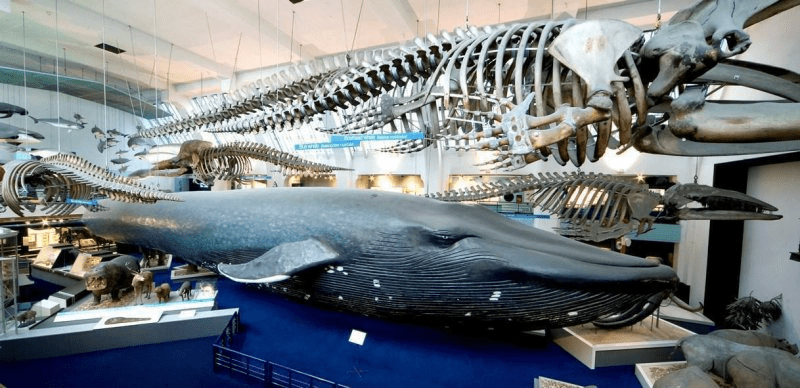

When my wife and oldest daughter were with me in London (August, 2025), we excitedly went to the Museum of Natural History to see some of the myriad of specimen that were on full display. To our astonishment it was a treasure trove of some of the most remarkable animal, mineral, vegetable collections in the world. We spent about four hours there before heading out to catch our breath. It was so thrilling to be there, expecially to see the Blue Whale skeleton and constructed mammals, that I skipped up every other step to see it fully and first among our group!

While we were at the Museum several names of American scientists came up over and over again for their discoveries. One was Othniel C. Marsh from New York. The other was Marsh’s paleantology arch-rival Edward D. Cope of Pennsylvania.

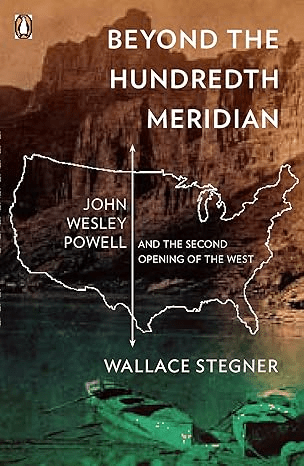

As a college student I came to know the Marsh name, as the professor and heralded museum curator, who had assembled the Hall of Dinosaurs at the Peabody Museum at Yale University. He was a legend in New Haven, and around the fossil world in his time. I later came across his name in conjunction with the research that John Wesley Powell was conducting in the 1860s. Powell was systematically mapping the western states of the US, particularly the uncharted lands beyond the 100th meridian. It was time to learn more about the Powell-Marsh relationship and, more specifically, who O.C. Marsh was and what made him tick?[1]

Wallace Stegner starts off his book characterizing OC Marsh as the opposite of John Wesley Powell. He cites Powell as having inadequate frontier education and no real laboratory skills, and summarily describes Powell as masquerading around as an expert in a half-dozen specialized fields, without any foundation of knowledge. Stegner summarizes that Powell should be catagorized as a “collector and not a scientist.” (Stegner, page 20) Marsh, on the other hand, was a Yale Sheffield Scientific School trained professional, who could discover more key fossils in two hours of field research than Powell could uncover and identify in two years. As a matter of fact in the summer of 1868, Marsh did just that: on a train trip to Nebraska he made a short excursion from Antelope Station, west of Omaha, where he picked up the first fossils that gave him a complete developmental history of the horse from eohippus to equus. Those bone findings of a three-toed horse led him to publish the clinching documentation of the theory of evolution. (Stegner, page 20) Charles Darwin himself was very impressed.

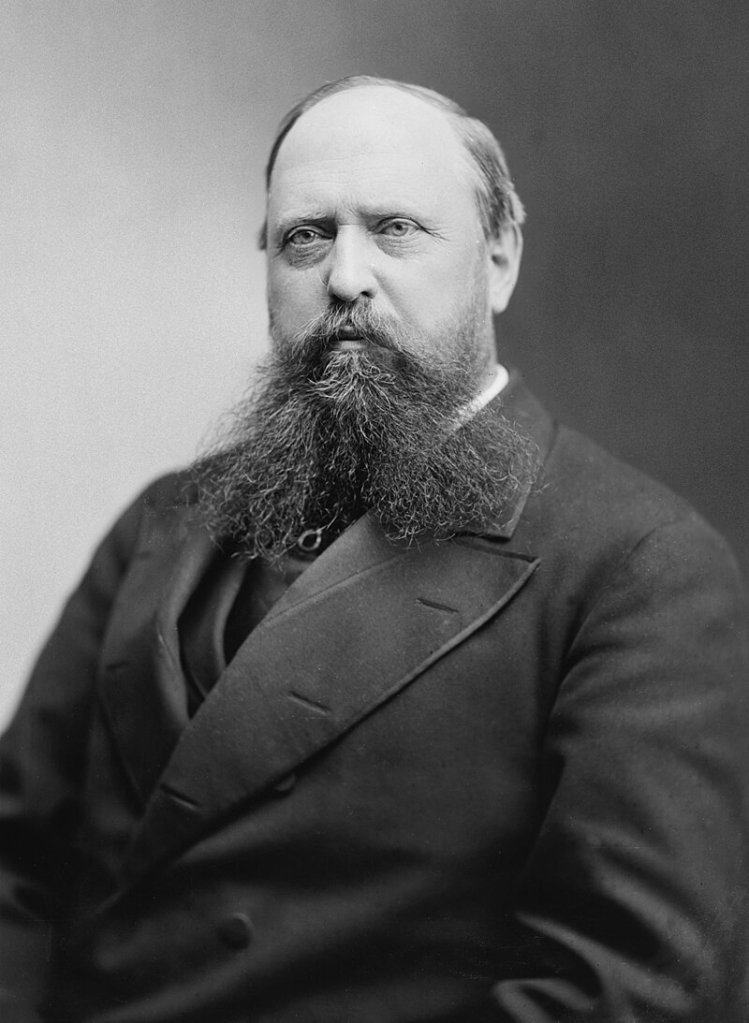

O.C. Marsh was a Yale professor of paleontology and curator of the Peabody Museum at Yale University. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the pre-eminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or description of dozens of new species, including the Stegosaurus and the Triceratops, and he developed some of the most studied theories on the origins of birds. He spent his undergraduate academic career as a student at Yale College and later served as a professor in the Sheffield Scientific School at the University. He also went on to serve as the president of the National Academy of Sciences.[2]

Marsh’s Early Life and Family

Othniel Charles Marsh was born on October 29, 1831, near Lockport, New York. His father’s and his mother’s families had both immigrated from England to America in the 1630s. The Marsh family name was originally spelled with a sixth letter e (as in Marshe). Othniel was born to Mary Gaines Peabody (1807–1834) and Caleb Marsh (1800–1865). He was the third of four children and the oldest son. His mother, Mary, died shortly after the birth of her fourth child in 1834. Othniel was three years old at the time. His father, Caleb, remarried two years later (1836) and the family moved to Bradford, Massachusetts. Soon after the move, Caleb’s business fortunes soured and the Marsh family’s early years were marked by financial challenges and debt troubles.

Finally gaining some financial stability, in 1843 Caleb Marsh purchased a farm in Lockport, New York. Othniel was twelve. As the eldest son, Othniel was expected to assist his father on the farm, however, the adolescent boy had other plans. Othniel much preferred excursions in the woods to performing his chores. Thus father and son had a contentious relationship. Among his childhood influences was Ezekiel Jewett, a former military officer and amateur scientist who influenced Othniel’s interest in the sciences. Jewett had been drawn to the area by the fossils unearthed by the enlargement of the Erie Canal, and the two would often hunt and prospect for bone specimens together.

By 1847, Othniel attended the Wilson Collegiate Institute and later the Lockport Union School to start his academic journey. Spurred on by his Aunt Judith Peabody, Othniel decided to enroll in Phillips Academy (Andover, Mass) in 1851. With the financial help of his uncle, George Peabody, and the determination to “take hold and really study,” he applied himself and graduated as the validictorian on his class in 1856.

During his summers off, he prospected for minerals in New York, Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, Canada. Upon his graduation from Phillips Academy, Marsh decided to attend Yale, rather than Harvard, where many of his relatives had graduated. He wrote a letter to his uncle George Peabody asking for financial support. Peabody agreed to cover Marsh’s expenses and to give him an allowance for spending money. The next September Marsh moved to New Haven. He applied himself again and was academically successful enough to graduate eighth in his class. After graduating from Yale College in 1860, Marsh traveled the world, studying anatomy, mineralogy and geology. Upon his return to New Haven, he obtained a teaching position of introductory science classes to Yale undergrads.

Using a scholarship he won for the best examination in Greek, Marsh was able to finance a master’s degree from Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School. While in graduate school, Marsh published his first scientific papers on minerals and vertebrate fossils from his Nova Scotia trips. It is assumed that those college summer trips inspired Marsh’s interest in vertebrate paleontology. He later obtained a master’s degree in paleontology in 1862.

The Bone Wars

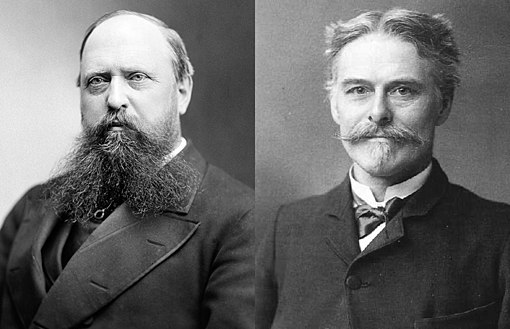

In their early days, the two Americans, Marsh from New York and Cope from Pennsylvania, spent many days together in Switzerland and Germany, and they become friends. Cope had much less formal schooling than Marsh; however, when they first met, Cope had already published thirty-seven papers, to Marsh’s one. After their many European meetings, they had expressed warm wishes in letters to each other and even named fossil species after each other. That early friendship did not stop them from soon vociferously jousting in the world of bone yards. The two paleontologists were seven years apart in age, Marsh – 32 and Cope – 25, but their rivalry heated up, while the two were studying in Europe. Their relationship simmered off and boiled on, mostly boiling ON, for decades.

For over twenty years (from the 1870s to 1890s), Marsh competed ferociously with rival paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in a period of described as “frenzied Western American fossil expeditions,” dramatically dubbed as the Bone Wars.

In 1866, with the acceptance of a gift from George Peabody, Yale established a chair of paleontology at the university and later the Peabody Museum. Marsh was given the chair position, but no salary was attached; this situation suited Marsh just fine, as he seemed more interested in research than teaching. In the late 1860s Marsh’s interests shifted entirely to paleontology, and after 1869 his other scientific contributions mostly ceased.

Trips East, then West

While teaching at Yale, Marsh toured the country, visiting museums to inform his planning of future bone exhibits at the Yale’s Peabody Museum. In 1868, he visited Edward Cope in New Jersey. Cope escorted him on a tour of the Marl pits, where he was finding many first-known fossils. Unbeknownst to Cope, Marsh would later pay the pit operators to divert their fossil finds to him instead of Cope. Marsh gained a reputation of “stealing” other paleontologists fossils, while he was on his research trips.

Marsh noted that Cope’s reconstruction of his newest fossil find, the aquatic reptile Elasmosaurus, was flawed: Cope had placed the head of the animal where its tail should have been. Marsh’s criticism wrankled Cope, and threatened his nascent career; Cope volleyed by critiquing errors in Marsh’s work, and moving in on areas Marsh was prospecting for new fossils. Their relationship had soured, and the duo became territorial, as well as professionally and personally hostile.

Marsh tried to ignore the noise by looking further afield than New Jersey for fossils. After visiting Chicago for a meeting of the American Association, Marsh elected to join other members to Omaha on a “geological excursion”; it was Marsh’s first trip to the far western United States, and it inspired him to return to prospect.

Marsh organized a series of private expeditions starting in 1870 to 1874, with the prospecting groups composed of current Yale students or recent graduates. The first of these trips uncovered more than a hundred new species of vertebrate fossils. After 1876, Marsh spent less time in the field and more time in the museum. He employed bone hunters who excavated the fossils and shipped specimens back to him in New Haven; he did not return west himself until 1879. When Cope began prospecting for fossils in the Bridger Basin, which Marsh considered “his” territory, their relationship deteriorated further into open hostility.

The Powell Factor

Marsh for a decade served as Vertebrate Paleontologist of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) from 1882 to 1892. Thanks to Maj. John Wesley Powell, head of the USGS, and Marsh’s contacts in Washington, DC, Marsh was placed at the head of the consolidated government survey in the late 1880s. Powell found Marsh to be an extraordinarily capable mover and shaker.[5]

As Stegner writes in his history: “Marsh singlehandedly ran Columbus Delano out of his job as Secretary of the Interior in the 1875 scandal about the cheating of Red Cloud’s Sioux. He was more than an illustrious scientist with a firsthand knowledge of the West; he was a man of power, shrewd in political manipulation, and solidly [financially] backed. And he was a far more eager ally for Powell than others would have been.” (Stegner, page 232) In the battles with Cope, who was a Hayden man, Marsh railed. Their former friendship had deteriorated into enmity that spilled out into the public domain. It seems nominally ironic that neither Marsh nor Cope could ‘cope with these situations,’ which increasingly fractured the two scientists judgment, feelings and emotions. They were both ‘stuck in the marsh’ of their own making.

When it came to the Geologic Surveys, Othniel Marsh thought that Hayden had blackmailed him into supporting the Hayden Survey in exchange for being elected to the National Academy in 1874. Marsh rejected the Hayden and Cope insults that followed. Marsh proved a strategic ally for Powell, who praised him personally as eminent, powerful and incorruptible; however, as far as scientific discoveries, Powell found him to be peculiarly mean, intemperate and vindictive. (Stegner, page 232)

In 1878, after Marsh returned from a paleontology trip to Europe, he helped assemble a committee to investigate all of the surveys, especially the ones by Hayden and others, who were Anti-Powell. Marsh pulled together a series of members to “stack the deck FOR Powell.” Powell need both the funding and the overwhelming approval of his “Report on the Lands of the Arid Region.” Marsh’s committee included Joseph Dana (fellow Yale grad), Simon Newcomb (US Naval Observatory), William Rogers, William Trobridge, and Alexander Agassiz (Harvard’s Peabody Museum curator). The committee members were for the most part without special bias or affiliation, which made for a water tight “inside job” for Powell. Marsh offered just the sort of relationships and influence Powell needed as he navigated the scientific and governmental obstacles to his work. (Stegner, page 234)[5]

Further along in his career, Marsh used his position as both the president of the National Academy and the head of Yale’s Peabody Museum, to be the virtual paleontological headquarters for all of Powell’s geologists, topographers, mappers, surveyors, and key officers in his studies and surveys of the land on the American western front. (Stegner, pages 272-273)[5]

Other Career Highlights & Lowlights

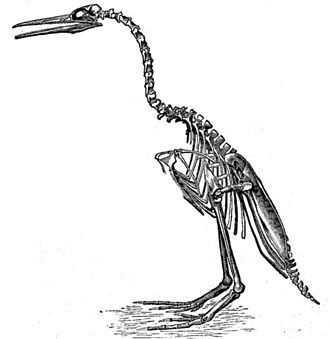

In 1880, Marsh caught the attention of the scientific world with his publication of Odontornithes: a Monograph on Extinct Birds of North America, which included his discoveries of birds with teeth. The members of congress at the time thought that such claims seemed preposterous and wrote about it with distain and incredulity. Despite the political blowback, Marsh’s skeletons helped bridge the gap between dinosaurs and birds, and provided invaluable support for Darwin’s theory of evolution. Charles Darwin read Marsh’s monograph and wrote a personal letter to O. C. Marsh saying, “Your work on these old birds & on the many fossil animals of N. America has afforded the best support to the theory of evolution, which has appeared within the last 20 years” (since Darwin’s publication of Origin of Species).

Stegner casts literary doubts as to Marsh’s scientific authenticity, when he quotes a New York Herald writer as claiming “Marsh … was an incompetent, a plagiarist, a cheat. He consistently published the work of his assistants as his own; he failed to pay his helpers; he destroyed fossils in the field, so that no one else could study them; he kept the enormous collections of the Geologic Survey in his Yale laboratory under lock and key, and refused other scientists access to them; and he had mixed them so hopelessly that no one would be able to sort them.” The reporter goes on to claim that his celebrated geneaology of the horse was a “pure theft” from the Russian scientist, Vladimir Kovalevsky.

Vladimir Kovalevsky, however, was as notorious in Europe as Cope was in America. Marsh replied to these allegations from his critics with clenched teeth. He wrote: “Kovalevsky was at last stricken with remorse [for his comments] and ended his unfortunate career by blowing out his brains.“[1]

Hesperornis regalis, a species of ancient flightless bird with teeth, as drawn by Othniel C. Marsh, and published in monograph, Odontornithes: A Monograph on Extinct Toothed Birds of North America

Between 1883 and 1895, Marsh was President of the National Academy of Sciences. The pinnacle of Marsh’s work with dinosaurs came in 1896 with the publication of his two major quartos, Dinosaurs of North America and Vertebrate Fossils, which demonstrated his unsurpassed world-wide knowledge of the subject of vertibrates. On December 13, 1897, Marsh received the Cuvier Prize of 1,500 francs from the French Academy of Sciences.

Bone Wars Changed Paleontology – Fossil Feud Legacy

According to Peter Dodson, Cope and Marsh “[have] left a legacy, and each was a distinguished researcher. But really it seems impossible to say one name without the other. Cope and Marsh.” Many of the fossils named by Marsh (three dinosaur groups and nineteen genera) have survived into today. Although only three of Cope’s named genera are still in use, Edward Cope published a massive record of 1,400 scientific papers. Scientist Mark McCarren called Cope “the only other American paleontologist, who could rival Marsh’s legacy.”

According to their peers, the most significant part of Marsh’s legacy is the collection of Mesozoic reptiles, Cretaceous birds, and Mesozoic and Tertiary mammals that now constitute the backbone of the collections of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Institution. The list of paleontological genera greatest hits for Marsh are included chronologically in the reference pages.[4] Cope’s greatest legacy is the sheer mass of scientific publications he wrote and the naming of the Camarasaurus and the Monoclonius.

Epitaph

As an observation it appears that Othniel Marsh never married, nor had children. His fossils were his family. He died in 1899, at his home in New Haven, Connecticut, at the age of 67. A possible epitaph for Marsh, is that he has been proclaimed to be “both a superb paleontologist and the greatest proponent of Darwinism in nineteenth-century America.” To anyone who loves going to museums, the legacy O.C. Marsh leaves for Yale and the Peabody Museum is complicated, the legacy his wars leave for the study of dinosaurs is never ending. Many thanks, O.C.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

References:

[1] Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. Penguin Books, New York, 1954.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Othniel_Charles_Marsh

[3] George Peabody was a banking financier and philanthropist of epic scale. He was also a signficant philanthropist for the Marsh family, especially Onthiel C. Marsh. Peabody’s bank in London took on Junius Spencer Morgan (father of J. P. Morgan) into partnership in 1854 to form Peabody, Morgan & Co., and the two financiers worked together until Peabody’s retirement in 1864. Peabody, Morgan & Co. then took the name J.S. Morgan & Co.

It is interesting to note that Peabody, Morgan & Co. spawned many banking offspring. Starting with the former UK merchant bank Morgan Grenfell (now part of Deutsche Bank), the list also includes the international universal bank JPMorgan Chase and the investment bank Morgan Stanley can all trace their roots back to Peabody’s first bank.

On the philanthropic side of the ledger, Peabody truly loved his family name and he was equally magnanimous. Note the following instututions who owe their existence to George Peabody.

- 1852, The Peabody Institute Library), Peabody, Mass: $217,000

- 1856, The Peabody Institute Library of Danvers) Danver, Mass: $100,000

- 1857, The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland: $1,400,000.

- 1862, The Peabody Donation Fund, London: $2,500,000

- 1866, The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University: $150,000

- 1866, The Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University: $150,000

- 1866, The Georgetown Peabody Library, the public library of Georgetown, Mass: sum unknown

- 1866, The Thetford Public Library in Thetford, Vermont: $5,000

- 1867, The Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass: $140,000

- 1867, The Peabody Institute, Georgetown Branch, DC Public Library, District of Columbia: $15,000

- 1867, Peabody Education Fund: $2,000,000

- 1875, The Peabody College of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee: sum unknown

- 1877, Peabody High School, Trenton, Tennessee: sum unknown

- 1901, The Peabody Memorial Library, Sam Houston State University, Texas: sum unknown

- 1913, George Peabody Building, University of Mississippi: sum unknown

- 1913, Peabody Hall, the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, University of Arkansas: $40,000

- 1913, Peabody Hall, the School of Philosophy and Religion), University of Georgia: $40,000

- 1913, Peabody Hall, the Criser Student Services Center, University of Florida: $40,000

- 1914, Peabody Hall, the college of Human Science & Education, Louisiana State University: sum unknown

- 1914, Peabody Hall, the Office of the Dean of Students and Admissions, University of Virginia: sum unknown

[4] The list of following genera was discovered and authenticated by O.C. Marsh, while serving as a professor at Yale University and the curator of the Peabody Museum at Yale.

- Allosaurus (1877)

- Ammosaurus (1890)

- Anchisaurus (1885)

- Apatornis (1873)

- Apatosaurus (1877)

- Atlantosaurus (1877)

- Barosaurus (1890)

- Brontosaurus (1879)

- Camptosaurus (1885)

- Ceratops (1888)

- Ceratosaurus (1884)

- Claosaurus (1890)

- Coelurus (1879)

- Coniornis (1893)

- Creosaurus (1878)

- Diplodocus (1878)

- Diracodon (1881)

- Dryosaurus (1894)

- Dryptosaurus (1877)

- Hesperornis (1872)

- Ichthyornis (1873)

- Labrosaurus (1896)

- Laosaurus (1878)

- Lestornis (1876)

- Nanosaurus (1877)

- Nodosaurus (1889)

- Ornithomimus (1890)

- Pleurocoelus (1891)

- Priconodon (1888)

- Stegosaurus (1877)

- Torosaurus (1891)

- Triceratops (1889)

[5] O. C. Marsh was one of the men with whom John Wesley Powell found some of his strongest kinship. The exploration of the relationship is outlined and discussed in another Powell’s Pals post on Marsh and eight other scientists and explorers from the Powell era.