Birds: Avocets and Stilts

It is funny how memory works … sometimes it is arrives with odors, like freshly cut grass or that special perfume that takes you back to summer in Pennsylvania or a romantic night at that restaurant. Other times it is triggered by a phrase, like pre-existing condition, that takes you right back into that conversation with Lynn Shanholz, your new CFO, who made sure that the new arriving baby would get the appropriate medical coverage. To me, often times I find memories that recall trails I have hiked, marathons I have run or paths I have taken, even from decades ago. I also have a memory bank full of “when was the first time I saw …” When I first saw that bird….

The other day, my wife, Tracy, said she was flying to an event in Carmel Valley, California. Immediately I felt transported back to a road between San Jose and Santa Cruz, somewhere near Gilroy and Hollister, where I drove past some shallow ponds near the macadam. I pulled off the main road and took out my binoculars. There I spotted these magnificent birds wading in those shallow ponds. I felt introduced to them for the first time.

I had seen these waders in bird books for years; however, there is no feeling for a birder more satisfying than identifying a beautiful species for the first time. Stilts and Avocets, avocets and stilts, they always are strung together for me with the Carmel Valley, because that is how memory works for me. There they are in my mind’s eye, wading together in the pools by the road to Carmel.

Spoiling the uniqueness in these birds was a fact that they are plentiful (not endangered) and in the same family of waders, the Recurvirostridae family, so of course they would be seen and stitched together. As my kids would say, “Well, duh, daddio, they are in the family!“

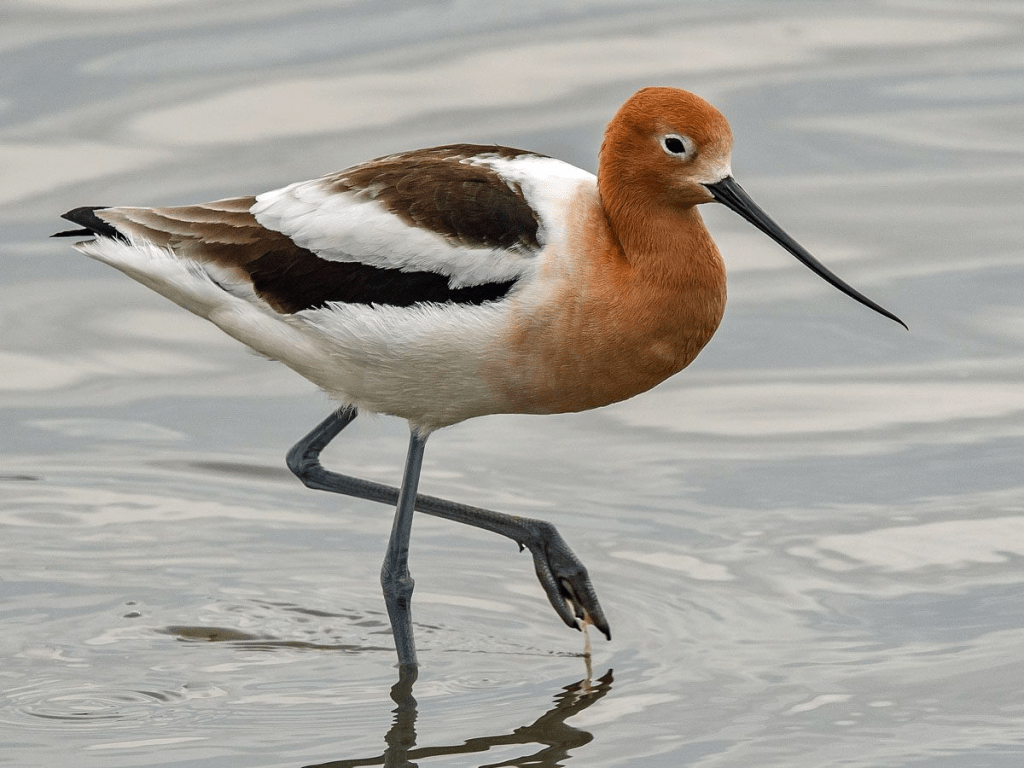

American Avocet

The American avocet (Recurvirostra americana) is a large wader in the avocet and stilt family, Recurvostridae, found in North America. The avocet spends much of its time foraging in shallow water or on mud flats, often sweeping its bill from side to side in water as it seeks crustaceans and insects.

There is even a too thin for me, uncomfortable bike seat that is named after the bird:

The American avocet was formally described in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus‘s Systema Naturae. Gmelin placed this species with the pied avocet in the genus Recurvirostra and coined the binomial name Recurvirostra americana. Gmelin based his description on that by the English ornithologist John Latham who in 1785 had described and illustrated the American avocet in his A General Synopsis of Birds. Latham cited the earlier publication by William Dampier and also that by Thomas Pennant. The genus name combines the Latin recurvus meaning ‘bent’ or ‘curved backwards’ with rostrum meaning ‘beak or bill’.

The American avocet is a member of the order Charadriiformes, which includes shorebirds, gulls, and alcids. Its family, Recurvirostridae, includes stilts and avocets. The genus Recurvirostra includes three other species: the Andean avocet, the pied avocet, and the red-necked avocet.

The American avocet measures 40–51 cm (16–20 in) in length, has a wingspan of 68–76 cm (27–30 in) and weighs 275–420 g (9.7–14.8 oz). The bill is black, pointed, and curved slightly upwards towards the tip. It is long, surpassing twice the length of the avocet’s small, rounded head. Like many waders, the avocet has long, slender legs and slightly webbed feet. The legs are a pastel grey-blue, giving it its colloquial name, blue shanks. The plumage is black and white on the back, with white on the underbelly. During the breeding season, the plumage is brassy orange on the head and neck, continuing somewhat down to the breast. After the breeding season, these bright feathers are swapped out for white and grey ones. The avocet preens its feathers, commonly considered to be a comfort movement.

The call has been described as both a shrill and melodic alarm bweet, which rises in inflection over time. Avocets use three distinct calls: common call, excited call, and broken wing call. The common call is a loud repeated wheep. The excited call has a similar wheep sound, but it speeds up rather than having an even rhythm. Lastly, the broken wing call is noticeably different from the other two calls. It is a distressed screech sound, and like the Killdeer, it’s call is loud and alarming rather than melodic.

Black-Necked Stilts

The Black-Necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) is a locally abundant shorebird of North and South American wetlands and coastlines. It is found from the coastal areas of California through much of the interior western United States and along the Gulf of Mexico as far east as Florida, then south through Central America and the Caribbean to Brazil, Peru and the Galápagos Islands. There is also an isolated population of stilts, the Hawaiian stilt, that is found in Hawaii. The northernmost populations, particularly those from inland, are migratory, wintering from the extreme south of the United States to southern Mexico, rarely as far south as Costa Rica; on the Baja California peninsula it is only found regularly in winter. Some authorities, including the IUCN, treat it as a synonym of Himantopus himantopus.[1]

It is often treated as a subspecies of the common or black-winged stilt, using the trinomial name Himantopus himantopus mexicanus. However, the AOS has always considered it a species in its own right, and the scientific name Himantopus mexicanus is often used. Matters are more complicated though; sometimes all five distinct lineages of the common stilt are treated as different species. The white-backed stilt from much of South America (H. melanurus when the species is recognized) is parapatric and intergrade to some extent with its northern relative where their ranges meet in northern Brazil and central Peru, would warrant inclusion with the black-necked stilt when this is separated specifically, becoming Himantopus mexicanus melanurus. Similarly, the Hawaiian stilt, H. m. knudseni, belongs to the (North) American species when this is considered separate; while it rarely has been treated as another distinct species, the AOS, BirdLife International and the IUCN do not.

The measurements of the Black-Necked Stilt are Length: 13.8–15.3 in (35–39 cm); Weight: 5.3–6.2 oz (150–180 g); and Wingspan: 28.1–29.7 in (71–75 cm). They have long pink legs, like a tall ballerina in pink tights and a long thin black bill. They are white below and have black wings and backs. The tail is white with some grey banding. A continuous area of black extends from the back along the hind neck to the head. There, it forms a cap covering the entire head from the top to just below eye-level, with the exception of the areas surrounding the bill and a small white spot above the eye. Males have a greenish gloss to the back and wings, particularly in the breeding season. This is less pronounced or absent in females, which have a brown tinge to these areas instead. Otherwise, the sexes look pretty much alike.

Downy feathers on the young are light olive brown with lengthwise rows of black speckles (larger on the back) on the upperparts – essentially where adults are black – and dull white elsewhere, with some dark barring on the flanks.

Where their ranges meet in northern Brazil and central Peru, the black-necked and white-backed stilts intergrade. Such individuals often have some white or grey on top of the head and a white or grey collar separating the black of the hindneck from that of the upper back.

The black-necked stilt is distinguished from non-breeding vagrants of the black-winged stilt by the white spot above the eye. Vagrants of the northern American form in turn are hard to tell apart from the resident Hawaiian stilt, in which only the eye-spot is markedly smaller. But though many stilt populations are long-distance migrants and during their movements can be found hundreds of miles offshore, actual trans-oceanic vagrants are nonetheless a rare occurrence.

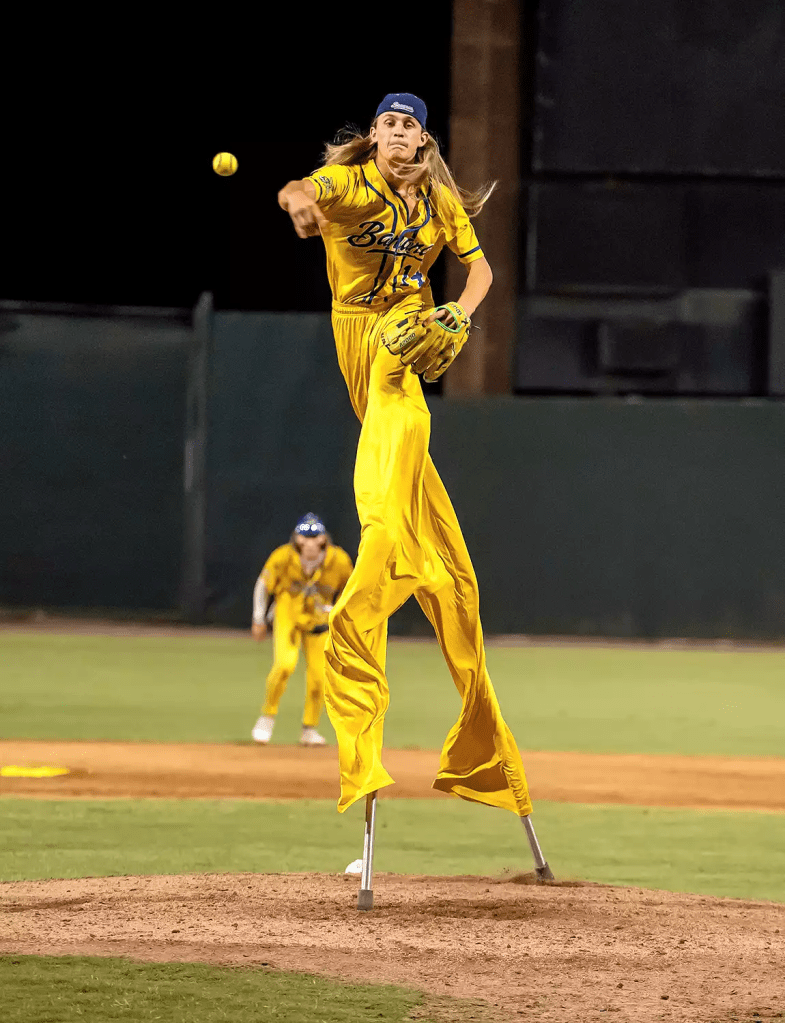

Dakota “Stilts” Albritton

Found mostly in the southern states, near Savanah, Georgia, this bird may be one of a kind. The measurements of Stilts Albritton are Length: 6 ft 7 in (200 cm); Weight: 210 lb (95 kg); and Wingspan: ~6 ft 10 in (208 cm).

Field Marks: Exceptionally long limbs and upright posture; known for graceful reach and uncommon balance. Usually found in gymnasiums, playgrounds, or near regulation hoops.

Range: Native to North America; migrates seasonally between indoor arenas and outdoor courts.

Habitat: Prefers hardwood surfaces and open lanes with good lighting. Often observed near clusters of teammates and the occasional photographer and gawking admirers.

Behavior: Social and competitive; communicates through hand signals and brief calls such as “ball!” and “mine!” Displays notable aerial ability when contesting rebounds.

Voice: Deep, resonant call; may emit short celebratory bursts after successful pitching or field plays.

Diet: High in protein and carbohydrates; frequently includes energy drinks, smoothies, and post-game pizza.

References: